Jonathan Erdman

The track history of Hurricane Alex in January 2016. The portion of the track in yellow indicates when the system was a non-tropical low from near the Bahamas to when it first became a subtropical storm, then again after it departed the Azores.

The track history of Hurricane Alex in January 2016. The portion of the track in yellow indicates when the system was a non-tropical low from near the Bahamas to when it first became a subtropical storm, then again after it departed the Azores.Five years ago this week, Hurricane Alex formed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, and it wasn't the first storm or hurricane to do so in January.

What would later become Alex began as an impressive, non-tropical low near the Bahamas on Jan. 6, 2016.

Two days later, the low passed near Bermuda, producing wind gusts up to 59 mph.

By Jan. 12, this low lost its cold and warm fronts, and enough thunderstorms percolated near the low-pressure center for it to be named Subtropical Storm Alex by the National Hurricane Center. A subtropical storm has features of both tropical and non-tropical systems, including a broad wind field, no cold or warm fronts, and generally low-topped thunderstorms displaced from the center of the system.

This is an infrared satellite loop showing the history of the non-tropical low near the Bahamas on Jan. 6-7, 2016, that would later become Subtropical Storm, then Hurricane Alex.

This is an infrared satellite loop showing the history of the non-tropical low near the Bahamas on Jan. 6-7, 2016, that would later become Subtropical Storm, then Hurricane Alex.Alex didn't stop there.

As thunderstorms continued to pump warmer air into the core of Alex's circulation, it eventually strengthened into a hurricane on Jan. 14 about 500 miles south of the Azores, a group of islands about 900 miles west of the Portuguese coast.

The satellite loop below shows the fascinating metamorphosis from non-tropical low to a hurricane from Jan. 10-14.

The sight of an Atlantic hurricane with a distinct eye on a mid-January global satellite image was surreal to even the most experienced meteorologists.

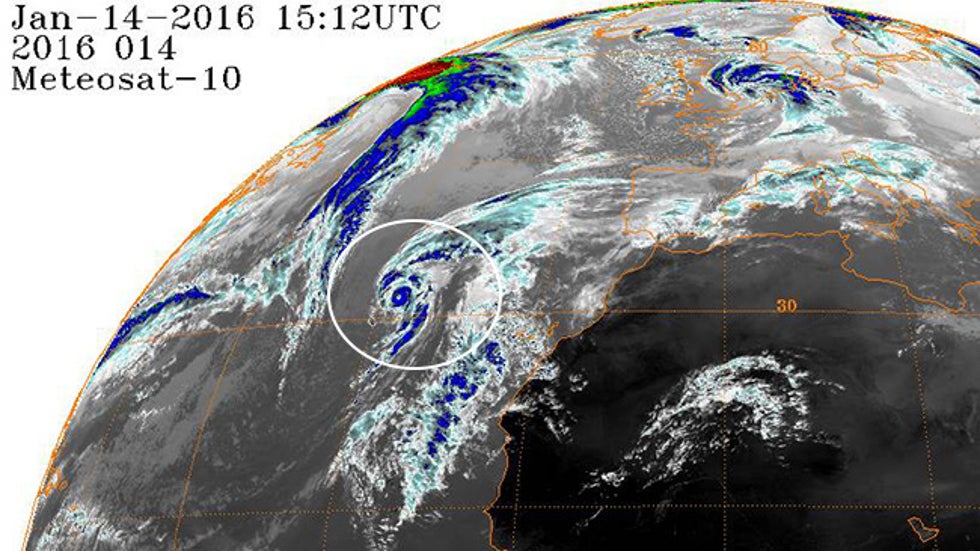

A Meteosat-10 infrared satellite image shows Hurricane Alex (circled) in the eastern Atlantic Ocean on Jan. 14, 2016, at 10:12 a.m. EST.

A Meteosat-10 infrared satellite image shows Hurricane Alex (circled) in the eastern Atlantic Ocean on Jan. 14, 2016, at 10:12 a.m. EST.Alex became the strongest January hurricane on record, with maximum sustained winds reaching 85 mph on Jan. 14.

It made landfall on the island of Terceira in the central Azores one day later as a tropical storm.

Alex then transitioned back to an extratropical cyclone – the type you're used to seeing on weather maps with fronts – and took a bizarre turn back toward Atlantic Canada, as The Weather Channel senior meteorologist Stu Ostro documented in a blog post.

A typical rule of thumb used by meteorologists is that water temperatures at least 26 degrees Celsius (about 79 degrees Fahrenheit) are needed to help generate tropical storms and hurricanes.

So how did Alex become a hurricane over water that was only around 22 degrees Celsius in January?

Air several thousand feet above the surface was cooler than usual. This made the atmosphere unstable and allowed thunderstorms to develop near Alex's core despite the marginally warm sea-surface temperatures.

"Usually, storms that form after the season do so from non-tropical sources, including upper-level lows and cold fronts," National Hurricane Center senior hurricane specialist Eric Blake told weather.com in 2017. "A common scenario is when an upper low cuts off and sits over warmer than normal water for a few days beneath a blocking pattern."

When that happens, clustering thunderstorms can turn what was originally a cold-core, non-tropical low into a subtropical storm, tropical storm, or in Alex's case, a January hurricane.

This Has Happened Before

As strange as a hurricane in the middle of winter sounds, it's not unprecedented.

One other hurricane was known to have formed in January in the Atlantic Basin.

A 1938 hurricane took a bizarre south-southwest hook in the central Atlantic Ocean between Africa and the Lesser Antilles, according to a 2014 reanalysis of historic hurricane tracks by NOAA's Hurricane Research Division.

On New Year's Eve 1954, Alice became a hurricane before slamming into the northern Leeward Islands at Category 1 intensity on Jan. 2, 1955.

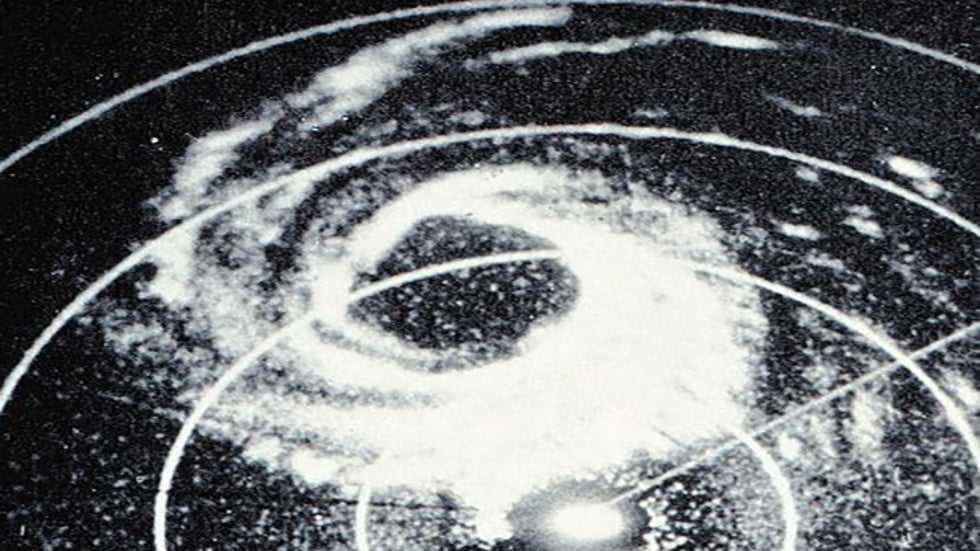

Radar image from the U.S.S. Midway of Hurricane Alice northeast of the British Virgin Islands on Jan. 1, 1955.

Radar image from the U.S.S. Midway of Hurricane Alice northeast of the British Virgin Islands on Jan. 1, 1955.A pair of unnamed tropical storms were found in reanalysis to have formed in January 1951 and 1978 in the central Atlantic Ocean.

The final named storm of the record 2005 hurricane season, Tropical Storm Zeta, formed on Dec. 30 but persisted until Jan. 7, 2006.

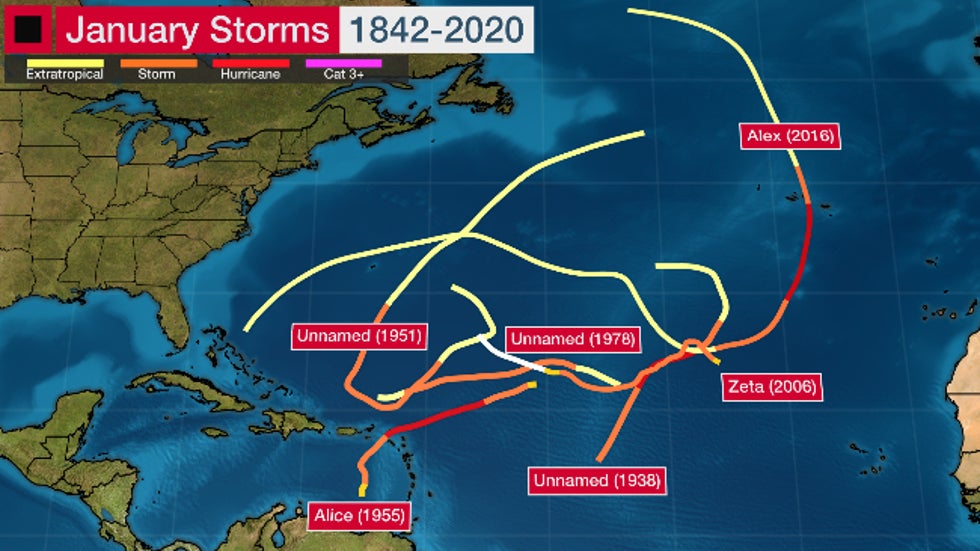

Here are the six storms or hurricanes that either formed in January, or were in progress into January, in records dating to 1842.

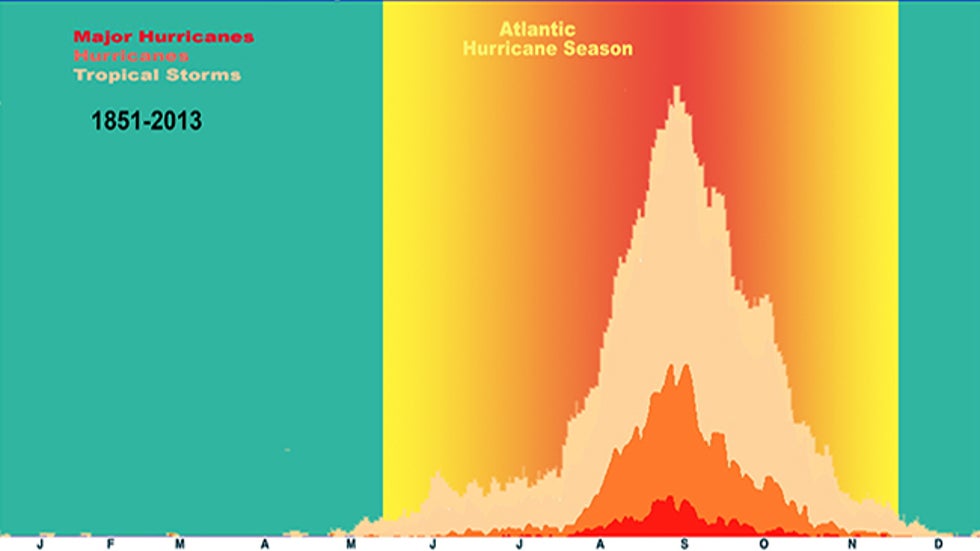

Here are the six storms or hurricanes that either formed in January, or were in progress into January, in records dating to 1842.According to NOAA's Hurricane Research Division, 97% of all Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes from 1851 to 2013 occurred within the June 1 to Nov. 30 official hurricane season.

Tropical storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin, by month, from 1851 to 2013. The June 1 to Nov. 30 hurricane season is highlighted in the warmer colors. A few named storms are shown in January along the left side of the graph.

Tropical storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin, by month, from 1851 to 2013. The June 1 to Nov. 30 hurricane season is highlighted in the warmer colors. A few named storms are shown in January along the left side of the graph.The other 3% formed in the "offseason," primarily in December, but also in January, February and March.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment