Tom Niziol

You are probably familiar with those beautiful tropical waterspouts often photographed off the coast of Florida or in the Bahamas.

You might not know, however, that waterspouts are also common on the Great Lakes this time of the year.

In fact, this week, there's a multi-day waterspout outbreak on the Great Lakes.

And this isn't the first such outbreak of the season.

According to the International Centre for Waterspout Research (ICWR), 42 waterspouts or funnel clouds were confirmed on August 5, alone – 41 over Lake Erie, and another one over Lake Ontario. The daily record for waterspouts on the Great Lakes at 67 on Oct. 20, 2013.

The Glossary of Meteorology defines a waterspout as "an intense columnar vortex – usually containing a funnel cloud – that occurs over a body of water and is connected to a cumuliform cloud."

In layman’s terms, that means a column of spinning air occurring over a body of water, connected to puffy cumulus clouds.

There are two types of waterspouts:

1. Tornadic: Associated with a rotating, supercell thunderstorm that produces extreme winds and damage. These are quite rare on the Great Lakes.

2. Fair-weather: A common type that occurs in generally fair weather without a connection to a dangerous supercell thunderstorm.

Fair-weather waterspouts typically have weak circulations and winds. The bigger ones produce wind gusts that can exceed 50 mph and flip a small boat or damage a dock if they come onshore.

Fortunately, these types of waterspouts also move relatively slowly and are most often visible over the flat expanse of the lake waters from a great distance, so there is ample time to get out of their way.

It also allows for some spectacular photos and videos.

Great Lakes waterspouts are also known as cold-air funnels. As the name implies, they occur when cooler air moves across the warmer waters of the Great Lakes.

By late July and early August, the Great Lakes are at their warmest. Water temperatures can rise to 80 degrees in the rather shallow water of Lake Erie.

It’s also the time of the year when cooler air from Canada begins to make its first venture across the border and over the Great Lakes.

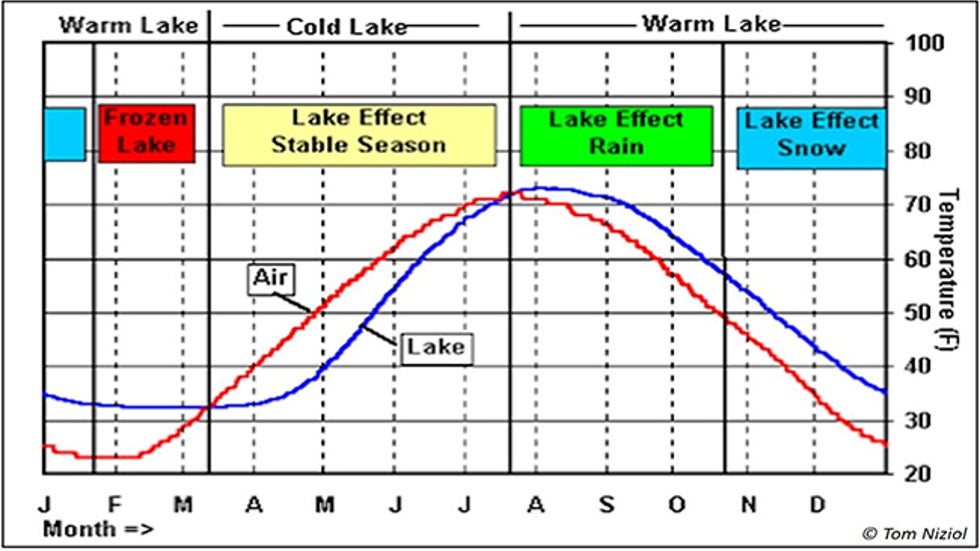

The average air temperature and Lake Erie water temperature at Buffalo, New York, defines the various lake-effect seasons. The waterspout season on the Great Lakes generally matches that time of the year when the water temperature is warmer than the air temperature. In the graph above, it roughly covers the months of August through October, which coincides with the period when lake-effect rain showers occur.

The average air temperature and Lake Erie water temperature at Buffalo, New York, defines the various lake-effect seasons. The waterspout season on the Great Lakes generally matches that time of the year when the water temperature is warmer than the air temperature. In the graph above, it roughly covers the months of August through October, which coincides with the period when lake-effect rain showers occur.There is a waterspout season – a subset of the same lake-effect season that produces those epic snowstorms in the late fall and winter on the Great Lakes.

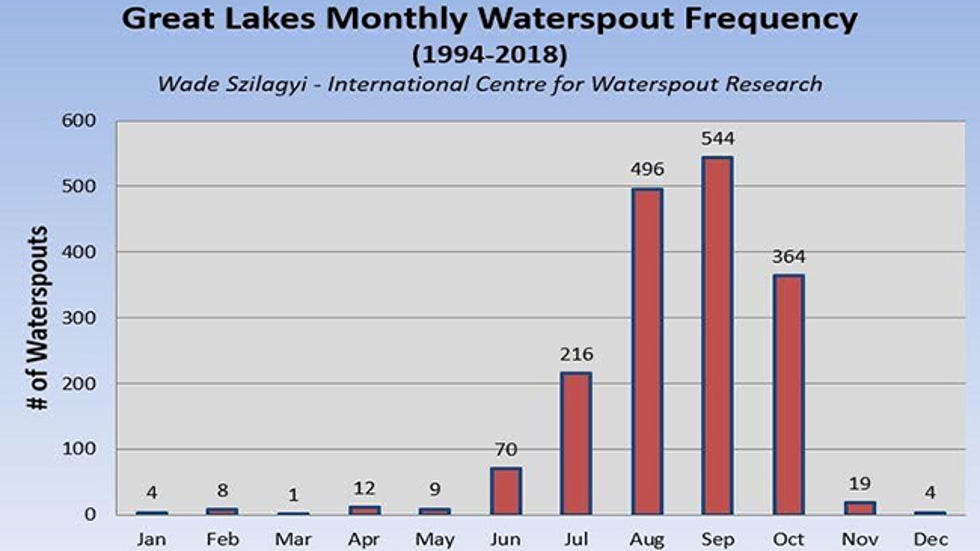

Waterspout season typically ramps up in the latter part of July and lasts into October. August and September are the most common months for Great Lakes waterspouts.

Monthly waterspout frequency on the Great Lakes from 1994 through 2010. The season typically begins in late July and extends through October.

Monthly waterspout frequency on the Great Lakes from 1994 through 2010. The season typically begins in late July and extends through October.So what does cold air moving across warm water have to do with waterspouts?

When that cool air moves across the warmer water, a steep drop in the air temperature develops from the warm lake surface upward a few thousand feet in altitude through the cooler air.

The drop in temperature with height is referred to as the "lapse rate." A steep lapse rate allows warm air near the lake surface to become very buoyant and rise rapidly like a hot air balloon into the colder air above.

Soon, rapidly developing cumulus clouds build, and below those clouds, the updrafts in that buoyant air strengthen.

If the winds near the surface are relatively weak, it allows for small, organized rotations to develop, which are lifted into a vertical column below those cumulus clouds. That rotating column of air gets stretched with the updraft, resulting in the spin-up of a waterspout.

The favorable conditions for waterspout formation (i.e. cold air outbreaks across warm waters of the Great Lakes) can be forecast to some degree.

The most common weather pattern to bring those colder temperatures aloft is a closed upper-level low that moves across the Great Lakes.

The ICWR issues daily forecasts for the potential for waterspout activity across the Great Lakes.

If you live near the Great Lakes, watch for those upper-level lows, head out to the lakeshore and if you’re lucky, you might just see one of these wonders of nature develop right before your eyes.

And, as alluded to earlier, it also marks a change of seasons when we begin to see lake-effect precipitation increasingly possible, as the air temperature trends cooler than Great Lakes water temperatures.

It’s time to get ready for the lake-effect season as it brings all sorts of interesting weather from now through winter.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment