Forecasting intensity changes in tropical storms and hurricanes remains a big challenge, and Hanna and Gonzalo provided another example of this last week.

Initial forecasts for Hanna from the National Hurricane Center (NHC) Wednesday night and Thursday morning called for maximum winds to be 45 mph near landfall on Saturday. Those wind speeds were incrementally boosted in subsequent forecasts, and by late Friday afternoon, the NHC predicted Hanna would be a hurricane before landfall with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph.

Hanna then made landfall in South Texas about 24 hours later on Saturday afternoon with winds of 90 mph, or more than double the initial wind-speed forecasts for the storm made less than 72 hours earlier.

Satellite view of Hanna's intensification over the course of 24 hours as it tracked toward landfall.

Satellite view of Hanna's intensification over the course of 24 hours as it tracked toward landfall.As that was happening, Gonzalo was going to the other extreme.

The NHC forecast issued early Friday morning called for Gonzalo to be a hurricane as it neared the southern Windward Islands on Saturday. Just 36 hours later, Gonzalo fizzled in the southeast Caribbean Sea.

Significant intensity forecast changes on short notice like these are not something new and have been noted in other recent hurricanes like Michael in 2018 and Harvey in 2017.

One reason this happens is that there can be small-scale changes to the structure of a tropical storm or hurricane that lead to intensification. These subtleties are particularly difficult for forecasters and computer models to predict far in advance, especially when real-time data from the storm is lacking.

Gonzalo was an example of the challenge small tropical storms often present to forecasters. Small tropical storms can rapidly intensify in a matter of hours when environmental conditions are favorable. On the other hand, they are more prone to having a quick demise than their larger counterparts when they encounter dry air and unfavorable upper-level winds.

Intensity forecasts have improved in recent years, according to a new NOAA study.

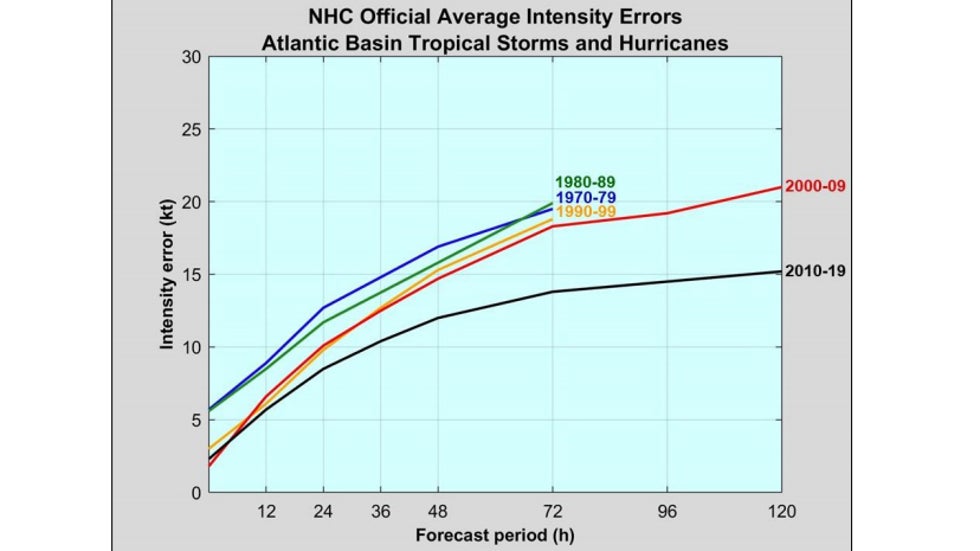

Intensify forecast errors from 2010 to 2019 decreased significantly when compared to previous decades (black line in the graph below). This is especially the case for forecasts made 36 to 120 hours from a storm's current location, the study said. For the NHC's five-day forecast point, or 120 hours in advance of a storm's current position, there was a 25% to 30% drop in intensity forecast errors.

The authors expect NHC intensity forecasts will continue to be more accurate in the next decade or so. However, they noted that there are limits.

While the intensity forecast for hurricanes will remain a challenge, forecasting the track of tropical cyclones has improved over the past couple of decades. This improved accuracy has likely saved lives and reduced unnecessary preparations and evacuations.

The bottom line is there may not always be five or more days notice that a powerful hurricane is going to impact an area, so it is important to be ready. It is a good idea to prepare for a hurricane that is one category stronger than forecast.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment