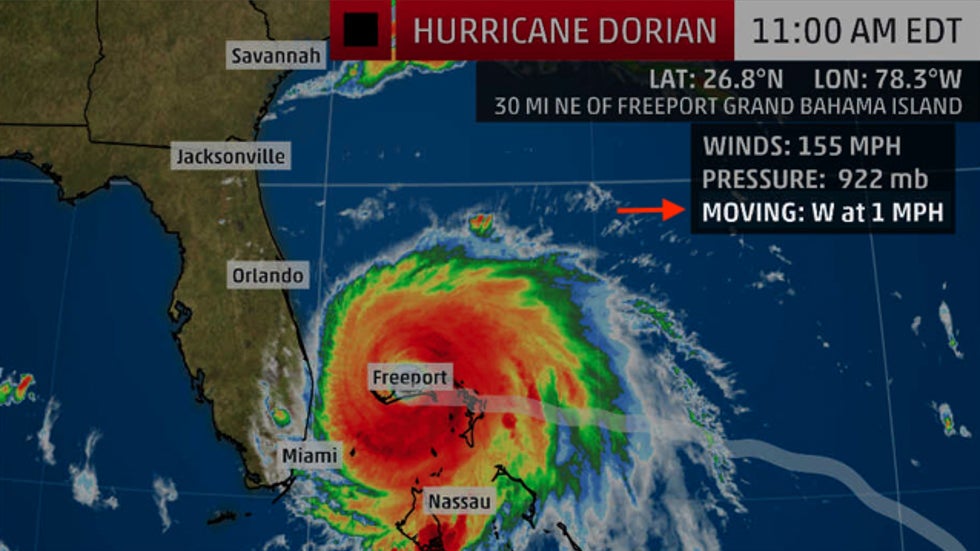

Satellite image and NHC advisory information while Hurricane Dorian was over the northwestern Bahamas on Sept. 2, 2019.

Satellite image and NHC advisory information while Hurricane Dorian was over the northwestern Bahamas on Sept. 2, 2019.How fast, or slow, a hurricane or tropical storm moves is an important factor that influences the severity of its impacts and is worth as much attention as its maximum winds.

Let's face it, a hurricane's winds tend to hog the spotlight. It's probably the first thing you notice on a graphic or while hearing a forecast.

The "Category 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5" labels you hear associated with a hurricane are based on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. That gives an idea of a storm's wind damage potential, but it doesn't necessarily correlate to the magnitude of its storm surge, rainfall or its ability to spawn tornadoes.

(MORE: The Majority of Hurricane Deaths are From Water, Not Wind)

But there is another statistic that doesn't usually stand out, but you'll typically see on a graphic. A storm's forward speed can play a major role in the damage it is able to inflict.

According to NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, a hurricane's average forward speed is about 11 to 12 mph in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea, and tropical Atlantic Ocean from 10 to 30 degrees North latitude.

It's those hurricanes and tropical storms that move much faster or slower that can amplify its destructive potential. There have been a number of each of these recently.

Slowpokes Can Be Catastrophic

If a hurricane is far out to sea and moving slower, there's more time for areas potentially threatened by the storm to prepare.

But when a storm slows down near or over land, its impacts are not only prolonged, but also greatly amplified.

In September 2019, Hurricane Dorian exploded into a Category 5 hurricane as it approached the northwestern Bahamas.

Then, the winds pushing the hurricane forward collapsed.

From Sept. 1 to 3, Dorian's eyewall lashed the northwestern Bahamas for an unfathomable 52 straight hours while at Category 4 or 5 intensity.

This crawl proved devastating. The intense winds drove a storm surge of up to 28 feet on Grand Bahama Island, according to the Bahamas Department of Meteorology (BDOM). Marsh Harbour, on Abaco Island, had tropical-storm-force winds for 72 hours.

While over the northwestern Bahamas, Dorian was the slowest-moving major hurricane - Category 3 or stronger - on record in the Atlantic Basin, crawling at 1 to 2 mph averaged over a 24-hour period, according to Robert Rohde, lead scientist at Berkeley Earth. The hashtag #1mph trended on Twitter for a time.

At least 74 residents were killed in the Bahamas, with damage there estimated at $3.4 billion, according to the BDOM. It will take years for these areas to recover from Dorian, in part due to this terribly timed stall.

Another factor that's amplified by a slowpoke storm is rainfall.

A storm's rainfall potential has little or nothing to do with the storm's wind intensity. It's largely a function of how fast it moves.

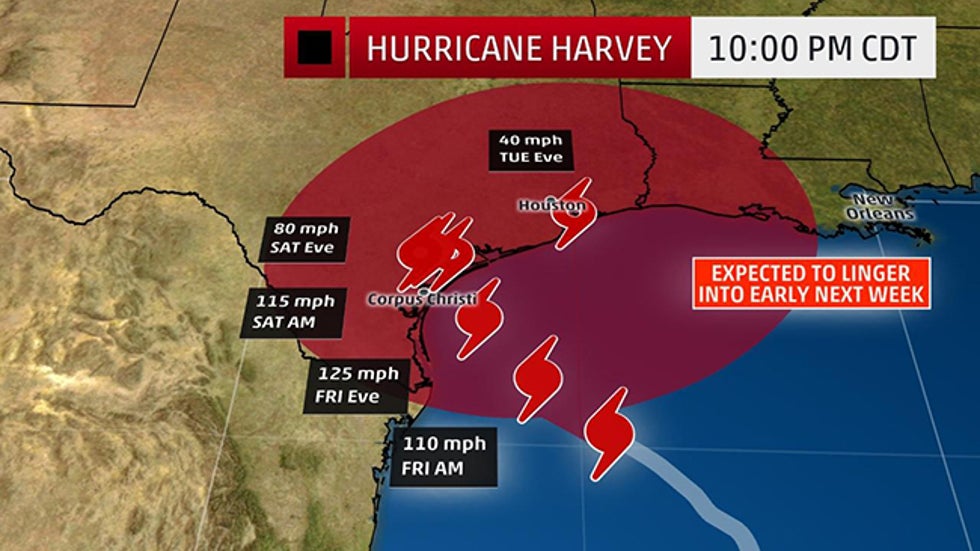

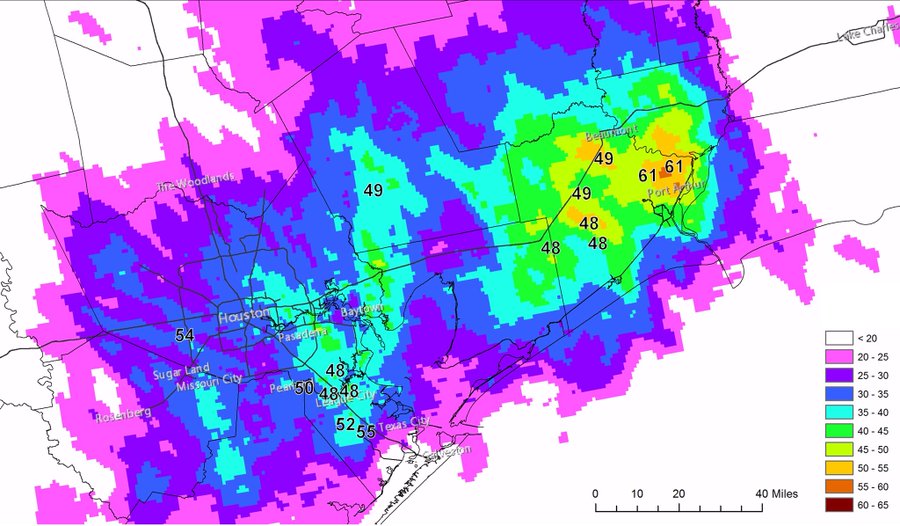

Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Texas coast at Category 4 intensity in 2017 with a destructive storm surge and damaging winds.

But it was Harvey's agonizingly slow meander over or near the Texas coast that made this a historic event.

Harvey's center of circulation stalled over South Texas on Aug. 26, then meandered slowly eastward into the Gulf of Mexico before making a final landfall near Cameron, Louisiana, on Aug. 30.

"Harvey was the most significant tropical cyclone rain event in United States history, both in scope and peak rainfall amounts, since reliable rainfall records began around the 1880s," National Hurricane Center forecasters Eric Blake and David Zelinsky wrote in the NHC final report on Harvey.

(MORE: We've Never Forecast This Much Rain Before)

#Harvey preliminarily set the US storm total rainfall record from a TC with 60.58 inches near Nederland Texas. Previous mark was 52.00” in Hawaii in 1950.

7 total stations recorded more rain than the previous US rainfall record of 52” and 18 (!) stations recorded more than previous mainland US record of 48”

Besides checking for the storm's forward speed in a graphic, one other clue a stall could happen is by looking at the forecast path of the storm.

When it no longer resembles a cone, but rather takes on the appearance of a circle, or there's little separation of forecast points, it suggests the storm is expected to stall.

(MORE: Why the Projected Path Doesn't Always Tell the Full Story)

The forecast "cone", or sphere, of the center of Hurricane Harvey from the National Hurricane Center issued on Aug. 24, 2017. Harvey's forecast stall caused the typical "cone" shape of this path to resemble a circle.

The forecast "cone", or sphere, of the center of Hurricane Harvey from the National Hurricane Center issued on Aug. 24, 2017. Harvey's forecast stall caused the typical "cone" shape of this path to resemble a circle.A 2018 study found Atlantic hurricanes and tropical storms, as well as those worldwide, appear to be moving slower than in past decades, potentially due to climate change.

Fast-Moving Storms

On the other end of the spectrum, hurricanes and tropical storms occasionally move much faster.

These lead-foot storms are challenging for meteorologists to stay ahead of and require those in the path to rush their preparations to completion.

This often happens when stronger steering winds aloft dip into at least part of the Atlantic Basin, or the storm moves far enough north to feel the effects of the jet stream.

All other factors equal, the faster a storm moves, the stronger the winds will be to the right of the center's path, since the storm's forward speed adds to its winds in this right-half of the circulation.

Faster-moving storms also are able to spread stronger winds farther inland before weakening.

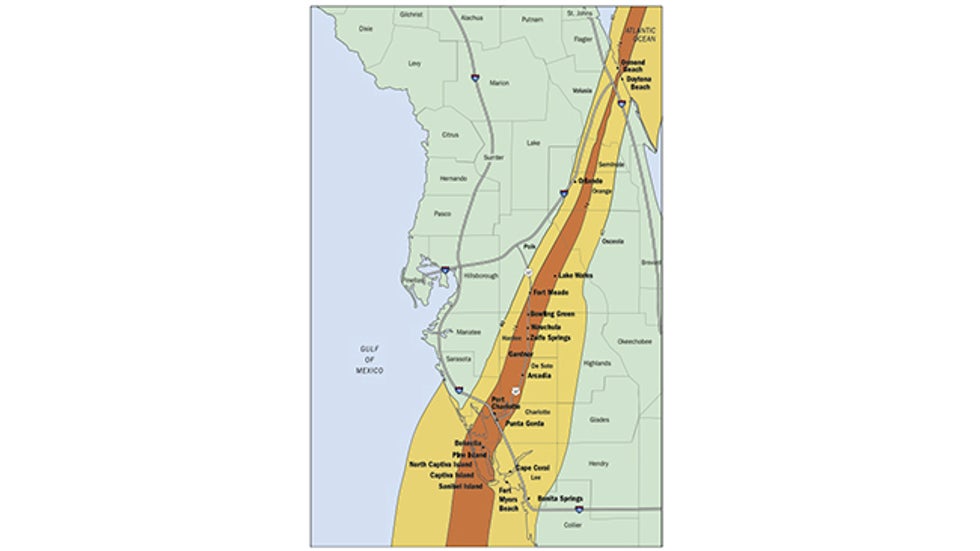

In 2004, Hurricane Charley made a Category 4 landfall in southwest Florida, then rapidly tore a 200-mile long path across the Florida Peninsula in less than eight hours, with an average forward speed of 25 mph.

The area of hurricane-force winds (in dark brown) and tropical-storm-force winds (in light tan) estimated by the NOAA H-wind model from Hurricane Charley over Florida on Aug. 13, 2004.

The area of hurricane-force winds (in dark brown) and tropical-storm-force winds (in light tan) estimated by the NOAA H-wind model from Hurricane Charley over Florida on Aug. 13, 2004.Despite its small size, Charley left behind a trail of wind damage resembling a large tornado from Punta Gorda and Port Charlotte in southwest Florida, to Orlando and Daytona Beach.

Two million Florida customers lost power – some for weeks.

(MORE: Surface Pressure a Better Indicator of Hurricane Damage Potential, Study Says)

One year later, after stalling and pummeling Cancún and Cozumel, Hurricane Wilma hit the gas pedal and roared across South Florida in less than five hours on Oct. 24, 2005.

The damage in Florida "included numerous downed trees, substantial crop losses, downed power lines and poles, broken windows, extensive roof damage and destruction of mobile homes," according to the NHC's final report. Some of the worst winds were on Florida's east coast rather than where it moved ashore in southwest Florida.

At the time, Wilma caused the largest disruption to electrical service ever experienced in Florida, according to the NHC report.

The most egregious recent example of inland wind damage from a fast-moving storm was 2008's Hurricane Ike.

After ransacking the upper Texas coast, the remnant of Hurricane Ike raced through the Ohio Valley, producing an estimated 1,600-mile-long swath of wind damage from Texas to upstate New York, including the eastern Great Lakes.

This home in Mayfield, Kentucky, was damaged by a tree downed by high winds from the remnant of Hurricane Ike on Sept. 14, 2008.

This home in Mayfield, Kentucky, was damaged by a tree downed by high winds from the remnant of Hurricane Ike on Sept. 14, 2008.Wind gusts over 70 mph were clocked in Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio, one day after Ike roared ashore in Texas.

Almost 2.6 million customers lost power in Ohio alone, according to the NHC's final report. Insured losses were estimated at $1.1 billion in the Buckeye State, rivaling damage from the Xenia tornado from the 1974 Super Outbreak, the report said.

More than 300,000 customers lost power in Louisville, Kentucky, a city record, and some had to wait almost two weeks for power to be restored, according to the National Weather Service.

These recent examples illustrate a storm's forward speed doesn't simply affect the storm's timing, but also the storm's impacts.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment