Jonathan Erdman

El Niño is likely to be in place through winter, and that could influence how much snow different regions of the U.S. pick up this season.

What is El Niño and how strong is it? This periodic warming of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific Ocean, El Niño first developed in June, and is the first El Niño in more than four years.

Since the end of August, its warm temperature anomalies have pushed above the threshold of a strong El Niño, at least 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than average.

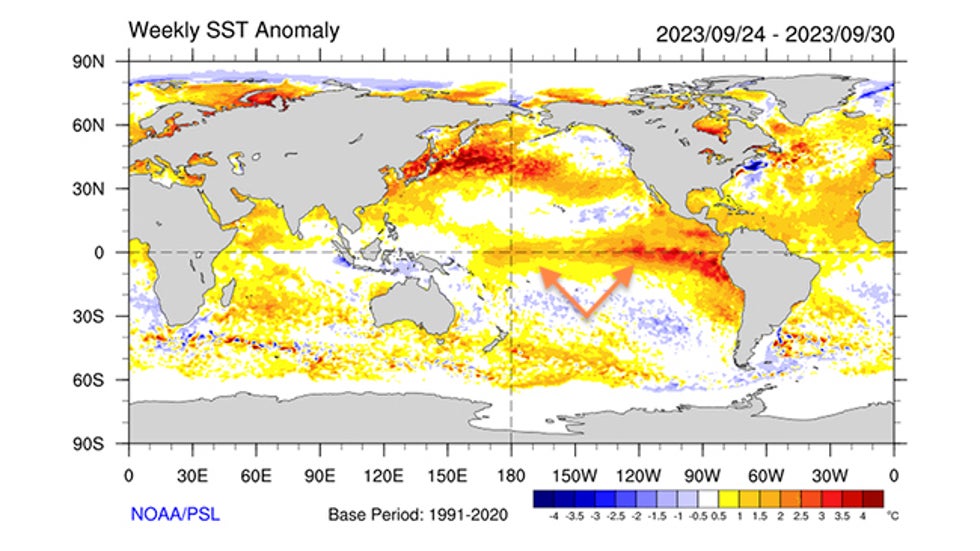

Sea-surface temperature departures from average (in degrees Celsius) during the last week of Sept. 2023. The El Niño is highlighted by the orange arrows.

Sea-surface temperature departures from average (in degrees Celsius) during the last week of Sept. 2023. The El Niño is highlighted by the orange arrows.Why does this strip of warm ocean water matter? El Niño and its cool counterpart La Niña can affect weather patterns thousands of miles away in the United States and around the world. Since most El Niños peak in late fall or winter, they can have their strongest influence in the colder months of the year.

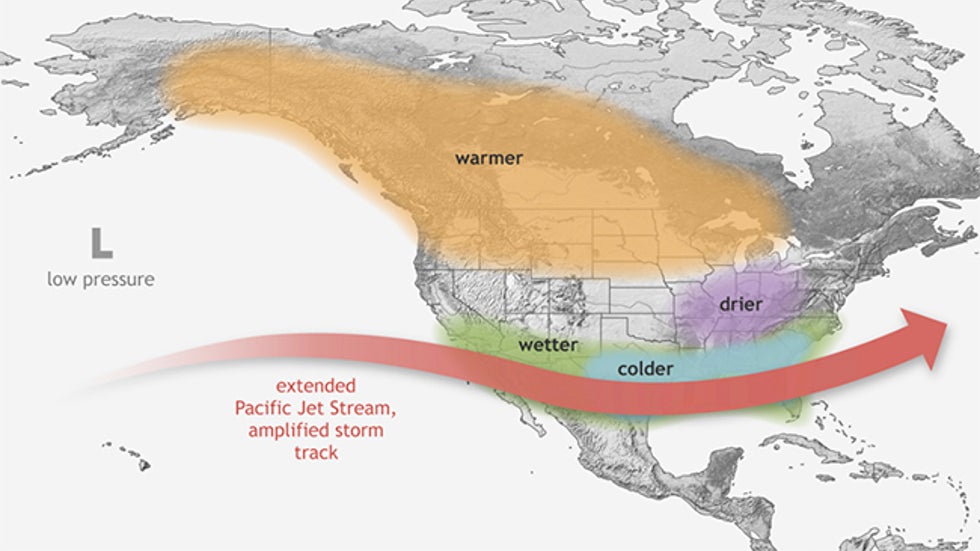

In general, the classic El Niño winter tends to be wetter than average through much of the southern U.S., from parts of California to the Carolinas, due in part to a stronger, more southern jet stream track.

Across much of the northern U.S., a stronger El Niño tends to produce a warmer winter.

Typical impacts during a stronger El Niño from December through February in North America.

Typical impacts during a stronger El Niño from December through February in North America.What does that mean for snowfall? We examined snowfall data since 1950 for about four dozen U.S. locations for which sufficient data exists and snowfall is typical at least once a year.

We grouped these seasonal snowfall totals into El Niño, La Niña and neutral (neither El Niño nor La Niña) seasons. For most of the locations, there were 26 El Niño, 25 La Niña and 22 neutral seasons of snowfall data.

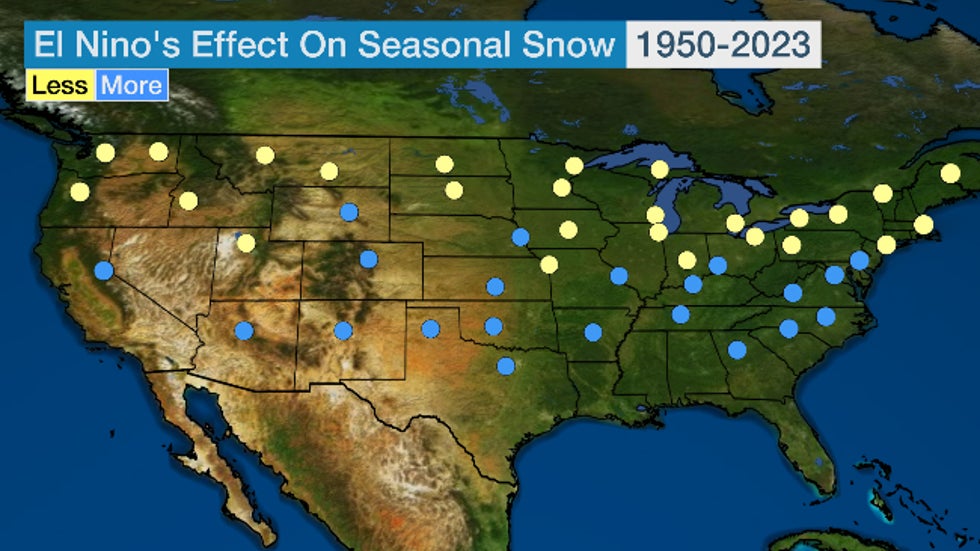

The map below shows El Niño's impact over the 73-year period.

You can see a north-south split. Winters are generally at least somewhat snowier than average across the South, but less snowy than usual across the northern tier.

Yellow/blue dots indicate locations that, based on National Weather Service data since 1950, see less/more snow during El Niño seasons, respectively.

Yellow/blue dots indicate locations that, based on National Weather Service data since 1950, see less/more snow during El Niño seasons, respectively.That general picture makes sense. The previously-mentioned, turbo-charged southern jet stream track usually brings a wetter winter to much of the South. If there's cold enough air in place, that could fall as snow (or ice) more often than usual.

Meanwhile, less northern snowfall is typically due to the polar jet stream's northward diversion into western Canada, keeping the region warmer and/or drier than usual.

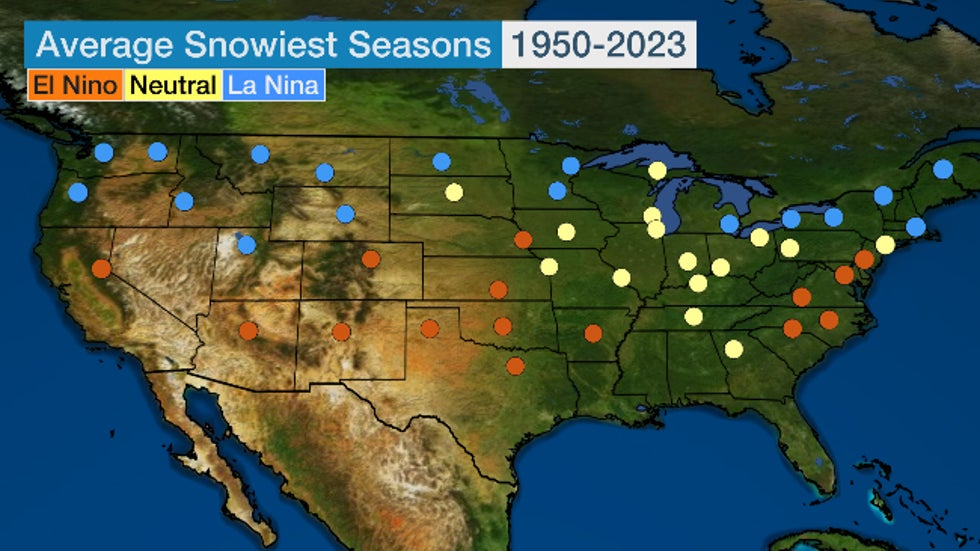

What delivers the snowiest seasons? In the map below, we show whether El Niño, La Niña or a neutral season delivers the most snow.

In some of these locations, the difference between El Niño, La Niña and neutral season snowfall is small, but a similar pattern is in place.

El Niño tends to be snowiest in the South, including the Front Range of Colorado, and also from the Carolinas to the mid-Atlantic. La Niña is snowiest in the Cascades and northern Rockies into upstate New York and much of New England.

Orange/yellow/blue dots indicate locations that, based on National Weather Service data since 1950, see snowier seasons (fall through spring) during El Niño/neutral/La Niña, respectively.

Orange/yellow/blue dots indicate locations that, based on National Weather Service data since 1950, see snowier seasons (fall through spring) during El Niño/neutral/La Niña, respectively.Here's a more in depth look at the El Niño snow "haves". Since no two El Niños are alike and the intensity of each could matter for impacts, we also examined strong El Niño seasons. One drawback is a limited sample size of only eight strong El Niño seasons since 1950.

What was most interesting in our investigation was how much the strength of the El Niño mattered.

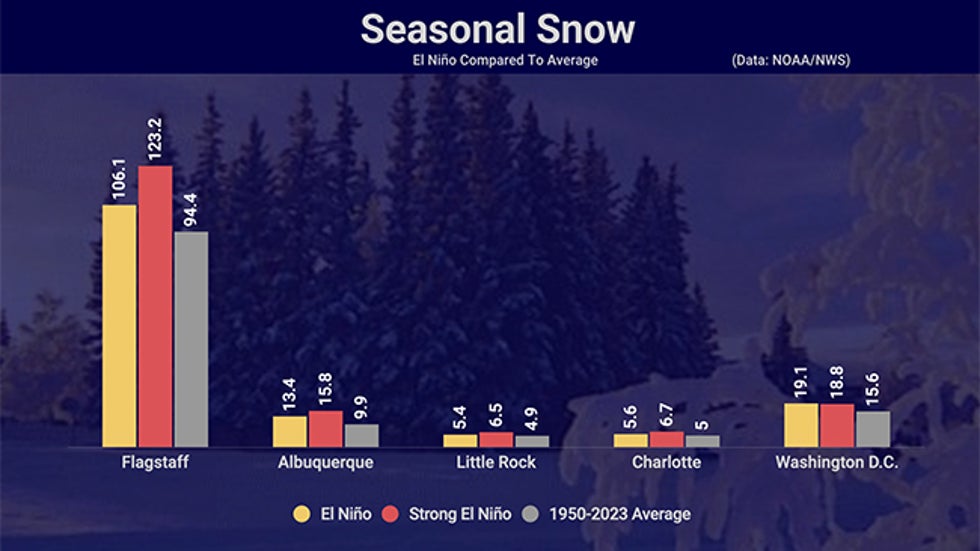

Below are some snowfall statistics for five cities in the snowier El Niño zone from Arizona to the nation's capital.

In each case, El Niño winters were snowier, but a stronger El Niño produced even more snow in all the cities below except Washington, D.C.

Typically snowy Flagstaff, Arizona, picked up more than 2 feet of additional snow in a strong El Niño season than average.

If this pattern holds, it would be quite the change in the mid-Atlantic from last winter. Both Philadelphia (0.3 inch) and Washington D.C. (0.4 inch) had one of their least snowy seasons on record in 2022-23, during a weakening La Niña.

Seasonal snowfall during El Niños (yellow bars) and strong El Niños (red bars), compared to 1950-2023 average (gray bars) in five southern cities.

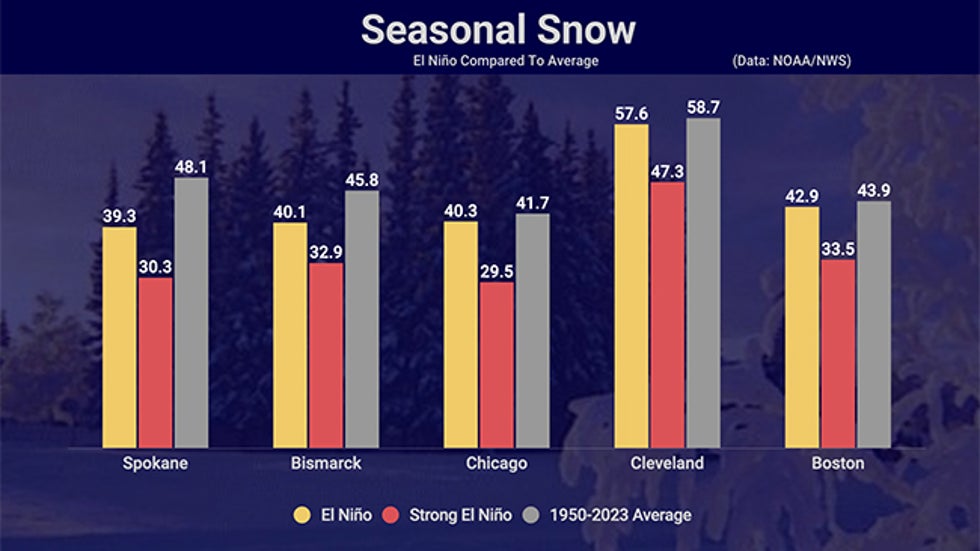

Seasonal snowfall during El Niños (yellow bars) and strong El Niños (red bars), compared to 1950-2023 average (gray bars) in five southern cities.Strong El Niños can be significant snow erasers in the North. Meanwhile, you can see El Niño's opposite effect in parts of the northern U.S.

In each of the cities below, an El Niño reduced seasonal snowfall by at least a small to moderate amount.

But strong El Niños took a much more significant bite out of the seasonal tally from Washington state to New England.

In Spokane, Washington, snowfall was almost 18 inches less in strong El Niños compared to average. In Chicago, that cut in snowfall was about a foot.

Same as above, but for five northern cities

Same as above, but for five northern citiesBut it's not just El Niño. Now we've come to the caveats.

First, not all El Niños are exactly the same. Even a stronger El Niño doesn't necessarily guarantee strong impacts on the weather pattern.

Just as the price of gasoline doesn't control the entire economy, El Niño isn't the only factor influencing winter weather.

Other ingredients could throw a monkey wrench into the snowfall scenario we described above.

The Greenland Block

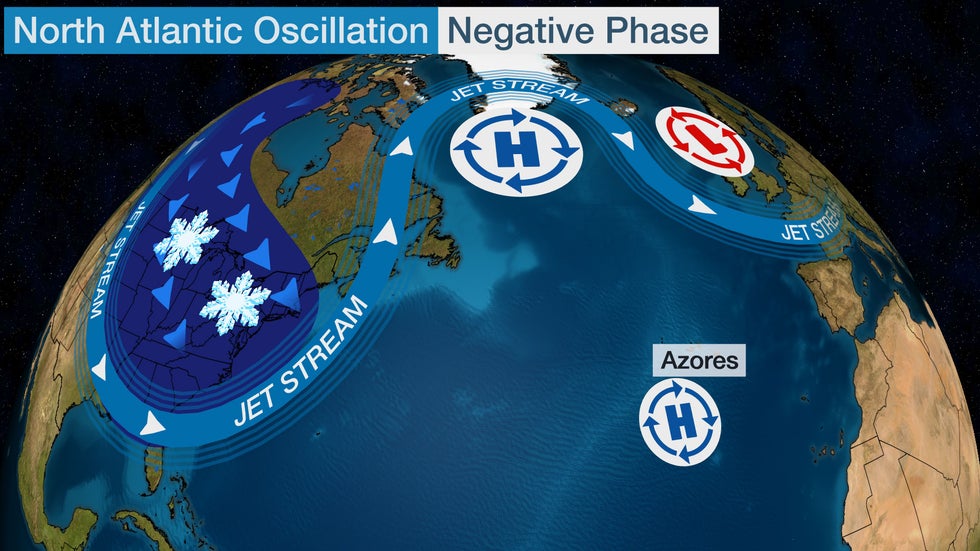

One is the degree to which blocking in the upper levels of the atmosphere occurs near Greenland this winter.

When high pressure aloft forms near Greenland, it blocks the west-to-east flow of the jet stream, forcing it to take a sharp southward plunge into the eastern U.S.

The area of blocking high pressure near Greenland forces a southward plunge in the jet stream across the eastern states when the North Atlantic Oscillation is in its negative phase. This leads to persistent cold temperatures and the potential for East Coast snowstorms.

The area of blocking high pressure near Greenland forces a southward plunge in the jet stream across the eastern states when the North Atlantic Oscillation is in its negative phase. This leads to persistent cold temperatures and the potential for East Coast snowstorms.Known to meteorologists as a Greenland block, this pattern delivers ample cold air from Canada and is an instigator for East Coast snowstorms.

How often this pattern develops in any winter season is difficult to forecast months ahead of time.

But if the Greenland block sets up frequently during a stronger El Niño winter, parts of the Southeast and mid-Atlantic can have a colder, snowier winter.

The Polar Vortex

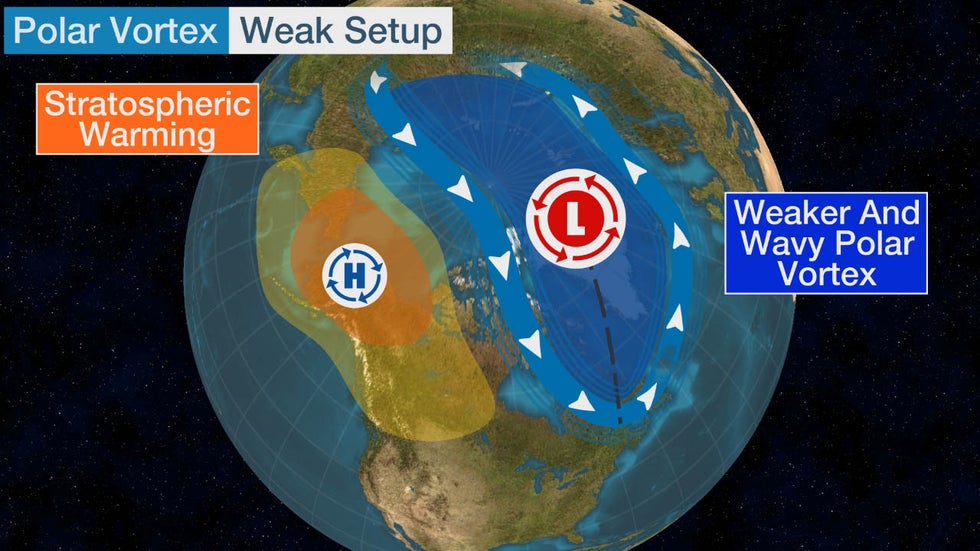

Another winter wild card difficult to forecast months in advance is the polar vortex, a whirling cone of low pressure over the poles that is strongest in the winter months.

When the polar vortex weakens, the cold air typically trapped in the Arctic can spill out into parts of Canada, the U.S., Asia and Europe because the jet stream becomes more blocked with sharp, southward meanders, sending more persistent cold air southward toward the mid-latitudes.

One such event triggered the historic February 2021 cold snap that crippled parts of the Plains, overriding the overall warm winter typically seen in the South during La Niña.

Example of a weak polar vortex in winter.

Example of a weak polar vortex in winter.El Niño gives us a first guess regarding a winter season's snowfall. Time will tell how much these other factors will muddy up that picture.

Jonathan Erdman is a senior meteorologist at weather.com and has been covering national and international weather since 1996. His lifelong love of meteorology began with a close encounter with a tornado as a child in Wisconsin. He studied physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then completed his Master's degree working with dual-polarization radar and lightning data at Colorado State University. Extreme and bizarre weather are his favorite topics. Reach out to him on X (formerly Twitter), Threads and Facebook.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment