Jonathan Erdman

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season has already zoomed past an average full season's worth of storms, and there may be more to come through October, possibly November, despite a stronger El Niño.

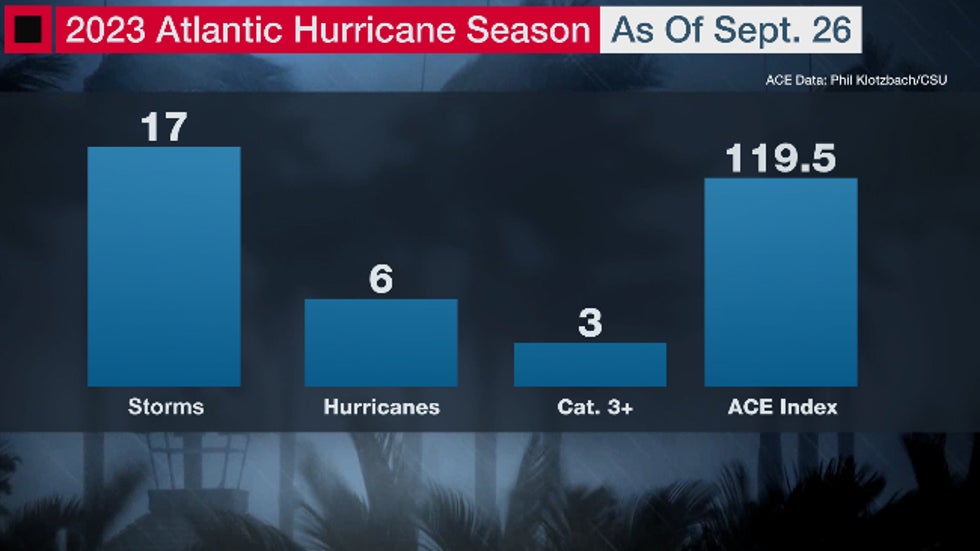

The average storm count is already in the rear-view mirror. As of this time this article was published, 17 storms have formed this season, including an unnamed subtropical storm off the East Coast in mid-January.

That's three more than both the average number of storms in an entire hurricane season and the total storms from last hurricane season.

According to Colorado State University tropical scientist, Phil Klotzbach, this named storm pace is tied with 2005 for third fastest on record, behind only 2020's 23 storms and 2021's 18 storms through Sept. 23.

In fact, we're getting close to the end of this season's list of names. If we do run out of names again this year, an alternate list of names would then be used, starting with "Adria".

2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season Names List

2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season Names ListThere have been plenty of hurricanes, too. Six hurricanes have formed through Sept. 26, just one shy of the average for an entire season.

Three of those became formidably intense, including Category 5 Hurricane Lee and Category 4 hurricanes Franklin and Idalia. That already matched the number of "major" (Category 3 or stronger) hurricanes from 2022.

We're over seven weeks ahead of the average activity pace. Using a parameter called the ACE index, which doesn't just count the numbers of storms, but also sums up how long they last and how intense they become, the season's tally as of Sept. 26 was more typical of what you'd find by mid-November, according to data compiled by CSU's Phil Klotzbach.

This year's ACE index topped all of 2022 by Sept. 13.

Atlantic hurricane season statistics as of Sept. 26, 2023.

Atlantic hurricane season statistics as of Sept. 26, 2023.Fish food, but landfalls, too. We've had many storms and hurricanes remain safely far from land over the central Atlantic Ocean, what some meteorologists refer to as "fish storms".

But we've also had landfalls. Most notably, Hurricane Idalia tied the Florida Big Bend's strongest hurricane landfall on record in late August.

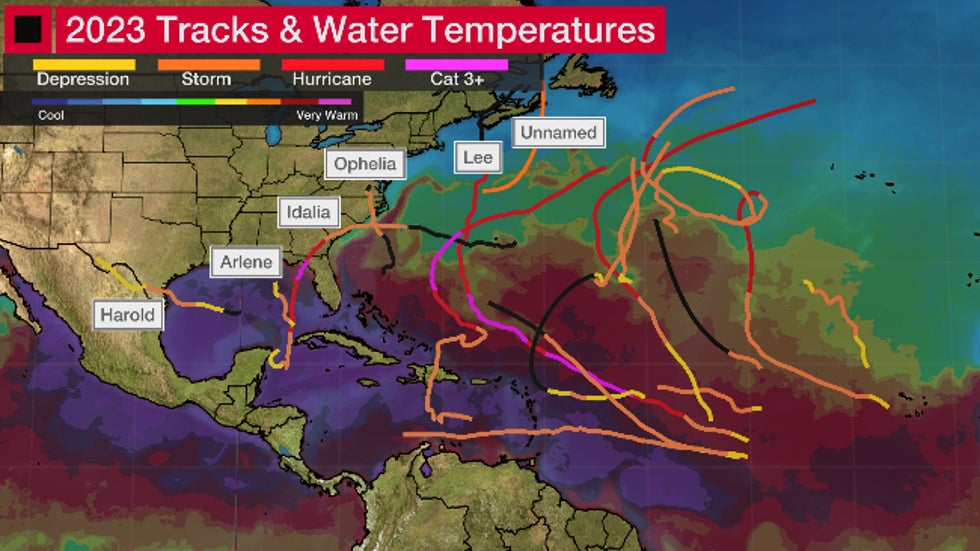

2023 Atlantic hurricane season tracks through Sept. 26, along with water temps also as of Sept. 26.

2023 Atlantic hurricane season tracks through Sept. 26, along with water temps also as of Sept. 26.Record warm water vs. El Niño, so far. This hurricane season shaped up to be a battle royal between an intensifying El Niño, which tends to reduce storm numbers especially in the Caribbean Sea and southern Gulf of Mexico, and basin-wide record warm water.

As you can see in the track map above, there have been plenty of storms and hurricanes in the stretch of Atlantic Ocean generally outside of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, capitalizing on that ample record warm water for this time of year. Fortunately, upper-level winds have aligned to steer most of those away from land.

While the number of storms has been fewer in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, it's not clear that's from El Niño's squashing effect. Wind shear since August hasn't been all that high in the western Caribbean or southern Gulf.

What about the rest of the season? An average hurricane season generates another four storms, two of which become hurricanes, from October through the season's end.

When examined in terms of the aforementioned ACE index, 22% of the season's activity lies ahead in October and November.

On one hand, past hurricane seasons during at least moderate strength El Niños have struggled to generate October or November hurricanes in the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of Mexico.

However, the warm water wild card, as alluded to above, is still there, particularly in the part of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico most prone to late-season storms.

(MORE: What's Typical In October And November In Hurricane Season)

It remains to be seen whether El Niño will flex its muscle on the atmospheric pattern late this season.

If you live in a hurricane zone, particularly in Florida and along the East Coast, don't let your guard down when the calendar turns to October.

Jonathan Erdman is a senior meteorologist at weather.com and has been covering national and international weather since 1996. His lifelong love of meteorology began with a close encounter from a tornado as a child in Wisconsin. Reach out to him on X/Twitter, Facebook and Threads.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment