Jonathan Erdman

Hurricane Calvin now inches westward in the Pacific Ocean, but while its forecast cone covers parts of Hawaii, it's not a major threat to the islands due to a number of factors that will weaken it significantly over the coming days.

Calvin didn't take long to become strong. After first becoming a tropical depression Tuesday, then a tropical storm Wednesday, Calvin rapidly intensified into the Western Hemisphere's first major hurricane of 2023 by Friday.

Fortunately, it did so over the Eastern Pacific Ocean far from land, more than 1,000 miles from Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

Calvin has begun weakening.

Its forecast path ends up near or over Hawaii. Calvin is expected to continue a general west-northwest track over the next five days.

That track would bring it near or over parts of Hawaii around the middle of next week, as you can see in the forecast path graphic below.

Projected Path

Projected PathCalvin won't be the same when it reaches Hawaii. There are several factors that will team up to weaken Calvin in the coming days before it arrives in Hawaii.

First, Calvin will meet markedly cooler water temperatures. That's because ocean currents bring cooler water southward off the West Coast of California then southwestward to an area of the Eastern Pacific Basin east of Hawaii where Calvin is forecast to move.

The less ocean warmth, the less potential energy is available for a tropical storm or hurricane to feed off.

Calvin will also encounter drier, sinking, more stable air in its path.

This weakens tropical storms and hurricanes because more stable air suppresses convection that sustains their existence. Dry air eats away at the core of tropical cyclones.

Finally, Calvin is expected to face some increased wind shear as it nears the islands.

These increasingly different winds aloft compared to winds near the ocean surface tilts a tropical cyclone and can blow its core thunderstorms away from its center of circulation.

Here's what we expect from Calvin once it reaches Hawaii. Given all that, we expect Calvin to pass near or over parts of the Hawaiian Islands around the middle of next week as either a tropical storm, tropical depression or remnant low, depending on how fast those negative factors described above act on it.

That doesn't mean Calvin won't have at least some impacts.

Increased swells will lead to high surf and rip currents along at least east and northeast-facing shores of the islands, particularly the Big Island ahead of and during Calvin's arrival.

Some locally heavy rain is possible as the system passes over the islands. That could lead to at least some localized flash flooding.

For now, residents and those planning to vacation in Hawaii should simply monitor the forecast for any possible changes in the next few days.

This "weakening before the islands" is fairly typical. For all the reasons we discussed earlier, many former Eastern Pacific hurricanes have weakened before moving westward to Hawaii.

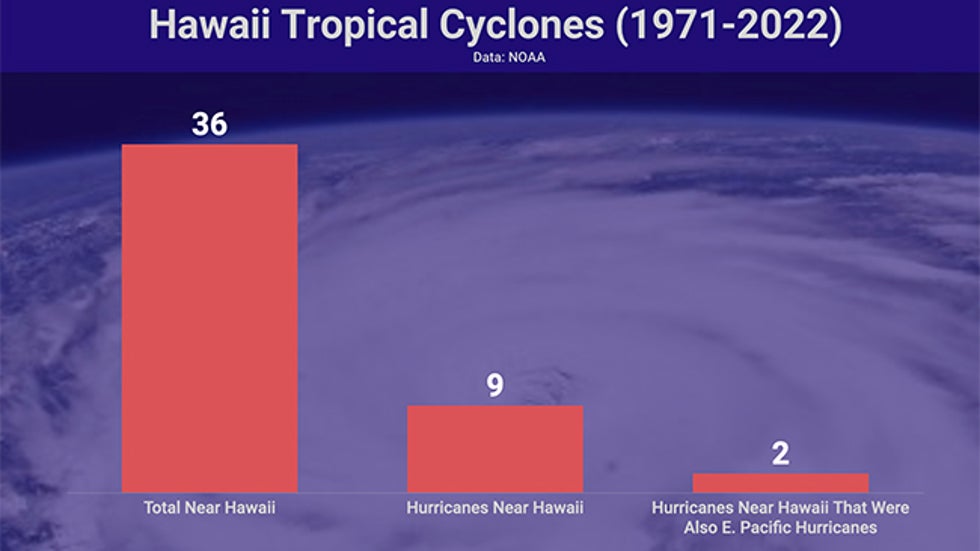

Since 1971, 17 Eastern Pacific hurricanes made it as far west as Hawaii, but weakened to either tropical depressions or storms by the time they arrived, according to NOAA's historical database.

There are a few exceptions.

In July 2020, Hurricane Douglas held onto Category 1 status as it brushed Hawaii, the closest hurricane to pass near Oahu in 61 years.

In general, Hawaii hurricanes are quite rare, but especially so if they come from the Eastern Pacific.

Of nine hurricanes that have passed within 60 nautical miles of Hawaii in NOAA's database since 1971, only three of those, Douglas in 2020 and Fico in 1978, were also Eastern Pacific hurricanes before they arrived.

Number of tropical depressions, storms and hurricanes within 60 nautical miles of Hawaii from 1971-2022, compared to hurricanes only and those hurricanes that were also once E. Pacific hurricanes.

Number of tropical depressions, storms and hurricanes within 60 nautical miles of Hawaii from 1971-2022, compared to hurricanes only and those hurricanes that were also once E. Pacific hurricanes.Hurricane Iselle weakened to a tropical storm before it arrived on the Big Island in August 2014 and therefore wasn't counted in that statistic.

Another, 2018's Hurricane Lane, tracked a bit too far south to be picked up by NOAA's 60 nautical-mile search criterion.

Despite that, Lane managed to dump prolific rainfall in parts of the islands. A 58-inch total at Kahuna Falls on the Big Island was not only a state all-time record for a tropical cyclone, but was also second highest only to 2017's Hurricane Harvey (60.58 inches) for heaviest rainfall from any U.S. tropical cyclone.

Jonathan Erdman is a senior meteorologist at weather.com and has been an incurable weather geek since a tornado narrowly missed his childhood home in Wisconsin at age 7. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment