Jonathan Erdman

The California drought, part of the most expansive western U.S. drought this century, is locked in place for awhile.

The impacts from this slow-motion disaster are only beginning to ratchet up as we head into the state's dry season.

Here are some facts on the status of the drought, the factors that triggered it, and the impacts already being felt.

The Most Dire Category

According to the latest Drought Monitor analysis as of May 25, not only is the entire state of California in drought, but 26% of the state is in "exceptional drought", the highest category.

The last exceptional drought in California was January, 2017, on the tail end of a multi-year drought. It was considered the worst in parts of the state in 450 years.

Current drought status, as of the May 25, 2021, Drought Monitor analysis. Progressively worse areas of drought are shown by the darker contours.

Current drought status, as of the May 25, 2021, Drought Monitor analysis. Progressively worse areas of drought are shown by the darker contours.Snowpack is Virtually Gone

California's Sierra snowpack typically supplies about one-third of the state's water once it melts later in spring and summer, recharging the state's reservoirs.

In 2021, a lack of spring snow and warm weather left the snowpack virtually gone by late May, about two months earlier than average, according to Peter Gleick, water and climate scientist at the Pacific Institute.

UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain referred to it as an "extremely rapid melt-out with very little runoff generated."

Instead, what little snowpack was left essentially melted, then evaporated or soaked into nearby dry soil.

What little snow was left in California's Sierra Nevada as shown by a snow depth analysis (in blue, left) and a GOES-West visible satellite image (right) on May 28, 2021.

What little snow was left in California's Sierra Nevada as shown by a snow depth analysis (in blue, left) and a GOES-West visible satellite image (right) on May 28, 2021.Reservoirs Not Replenished

According to the Sacramento Bee, the early-vanishing snowpack amounted to about 685,000 acre-feet of water that didn't replenish California's reservoirs, enough to supply up to 1.2 million households for a year.

That's left some of the state's reservoirs very low for late spring, and dropping.

Folsom Lake, a prime water source for the Sacramento metro area, hasn't been this low in late spring since the 1970s.

Lake Oroville, about 60 miles north of Sacramento, was less than half its average level for late May. Quite a contrast to just over four years ago when a huge hole opened in its spillway during prolonged heavy rain, which prompted evacuations and repairs that topped $1 billion.

With increased evaporation in the summer and the need to draw down some reservoirs to preserve fish populations in rivers, these levels will continue to inch lower over the next several months.

In this composite image a comparison has been made between an aerial view of California when the state's severe drought emergency was lifted in 2017 (top) and a week after California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a drought emergency in two counties in 2021 (bottom). **TOP IMAGE** OROVILLE, CA - APRIL 11: The Enterprise Bridge passes over a section of Lake Oroville on April 11, 2017 in Oroville, Calif. After record rainfall and snow in the mountains, much of California's landscape has turned from brown to green and reservoirs across the state are near capacity. California Gov. Jerry Brown signed an executive order Friday to lift the State's drought emergency in all but four counties. The drought emergency had been in place since 2014. **BOTTOM IMAGE** The Enterprise Bridge crosses over a section of Lake Oroville where water levels are low on April 27, 2021, in Oroville, Calif. Four years after then California Gov. Jerry Brown signed an executive order to lift the California's drought emergency, parts of the state have re-entered a drought emergency with water levels dropping in the state's reservoirs. Water levels at Lake Oroville have dropped to 42% of its 3,537,577 acre foot capacity.

In this composite image a comparison has been made between an aerial view of California when the state's severe drought emergency was lifted in 2017 (top) and a week after California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a drought emergency in two counties in 2021 (bottom). **TOP IMAGE** OROVILLE, CA - APRIL 11: The Enterprise Bridge passes over a section of Lake Oroville on April 11, 2017 in Oroville, Calif. After record rainfall and snow in the mountains, much of California's landscape has turned from brown to green and reservoirs across the state are near capacity. California Gov. Jerry Brown signed an executive order Friday to lift the State's drought emergency in all but four counties. The drought emergency had been in place since 2014. **BOTTOM IMAGE** The Enterprise Bridge crosses over a section of Lake Oroville where water levels are low on April 27, 2021, in Oroville, Calif. Four years after then California Gov. Jerry Brown signed an executive order to lift the California's drought emergency, parts of the state have re-entered a drought emergency with water levels dropping in the state's reservoirs. Water levels at Lake Oroville have dropped to 42% of its 3,537,577 acre foot capacity.Drought Emergency Declared

Given all this, California Gov. Gavin Newsom expanded a drought emergency to include 41 of the state's 58 counties on May 10, including all but Southern California.

The declaration gives the state more power to determine how limited water resources are prioritized.

At the time, Newsom also proposed allocating $5.1 billion for drought relief and resilience.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom holds a news conference in the parched basin of Lake Mendocino in Ukiah, Calif., Wednesday, April 21, 2021, where he announced he would proclaim a drought emergency for Mendocino and Sonoma counties.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom holds a news conference in the parched basin of Lake Mendocino in Ukiah, Calif., Wednesday, April 21, 2021, where he announced he would proclaim a drought emergency for Mendocino and Sonoma counties.Water Supply Concerns

While water supply wasn't yet a concern in the most of the Bay Area, some water use reductions have been either requested or in a few cases, ordered.

The state ordered some towns and vineyards along the Russian River to restrict water use, a rarely-used order, The San Francisco Chronicle reported.

Santa Clara County was likely to face mandatory restrictions after the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation reduced water shipments to the county's water district by more than 50%.

And in the Central Valley, some farmers are letting their fields lie fallow and are taking down orchards, the Sacramento Bee reported, due to lower allotments of water being provided from state and federal government agencies.

Sacramento residents have been asked to reduce their water usage by 10%.

According to the May 25 Drought Monitor summary, groundwater levels have dropped low enough in the Sacramento and San Joaquin River deltas that there is an increased risk of saltwater intrusion. Preparation is underway to install a $30 million barrier in the delta to keep the salt water out.

An aerial view as the sun sets beyond agricultural fields on April 21, 2021, near Bakersfield, Calif. California Gov. Gavin Newsom today declared a drought emergency in two counties following a winter with little precipitation. The order will allow the state to more quickly prepare for anticipated water shortages.

An aerial view as the sun sets beyond agricultural fields on April 21, 2021, near Bakersfield, Calif. California Gov. Gavin Newsom today declared a drought emergency in two counties following a winter with little precipitation. The order will allow the state to more quickly prepare for anticipated water shortages.Soil Moisture, Fire Concerns

Not surprisingly, soil moisture values in California and much of the Desert Southwest were in the lowest 1% of all values on record for May 26, according to NOAA's Climate Prediction Center.

And that's setting up yet another volatile fire season ahead.

According to the National Interagency Fire Center, the Energy Release Component - an index that captures how dry the vegetation is and, thus, how intense a fire can burn and how fast it can spread - is at or above record high levels for this time of year in California, levels more typical of June or July.

Soil moisture percentile on May 26, 2021. Much of the Southwest, including California, had soil moisture values in the lowest 1 percent on record for this time of year.

Soil moisture percentile on May 26, 2021. Much of the Southwest, including California, had soil moisture values in the lowest 1 percent on record for this time of year.Second Straight Dry Rainy Season

In records dating to 1850, the 2020-21 July-through-June water year (8.95 inches through May 27) is the third driest on record in downtown San Francisco, only 40% of its average rainfall.

Important for the severity of the drought, it's also the second straight dry water year in California.

Downtown San Francisco has picked up only 20.65 inches of rain over the past two water years. Only 1975 through 1977 (19.13 inches) was drier, according to Jan Null, a consultant meteorologist in the Bay Area.

Essentially, the Bay Area is more than one full year behind in precipitation, with a deficit since July 2019 of just over 25 inches.

That makes next winter and spring critical. If California has a third straight dry winter, the drought impacts could worsen substantially.

Months Until Significant Rain, Mountain Snow

Unfortunately, we're now into California's dry season.

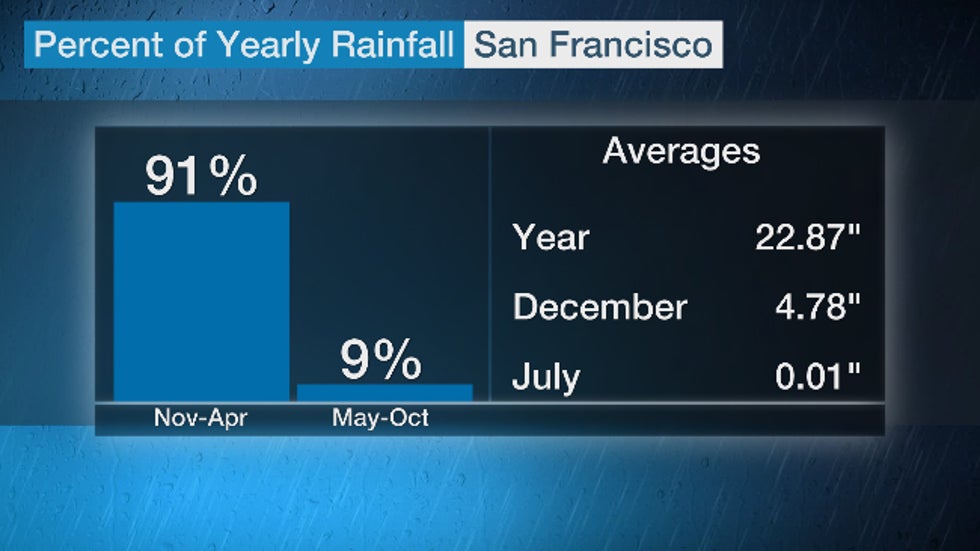

San Francisco picks up 91% of its average rainfall from November through April.

So, it will be months before any widespread rain and mountain snow will once again nourish the parched Golden State.

And, as a recently-published study has found, climate change is delaying the onset of California's rainy season deeper into fall, with serious consequences on the severity of wildfires later in fall.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment