Jonathan Erdman

Issuing tornado warnings is often more challenging than it may appear.

Most tornadoes are weaker, while some occur at night or are embedded in lines of thunderstorms. They can occur in more marginal severe weather environments or in places that don't often see tornadoes.

When you think of a tornado, perhaps the first image that comes to mind is the classic dark, stovepipe-shaped tornado you might see in the Plains, such as the example below, spawned by a long-lived rotating thunderstorm known as a supercell.

Photo of the Seymour, Texas, tornado on April 10, 1979. From the same parent supercell, this tornado preceded the Wichita Falls, Texas, tornado by about one hour.

Photo of the Seymour, Texas, tornado on April 10, 1979. From the same parent supercell, this tornado preceded the Wichita Falls, Texas, tornado by about one hour.Supercells produce the majority of all tornadoes, according to NOAA's National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL).

Tornadoes spawned by supercells are often easily detected by Doppler radar. They may exhibit the classic hook echo in reflectivity – a distinct, tight rotation in velocity imagery and occasionally a signature of debris lofted by the tornado known as a tornado debris signature.

This is fortunate because it turns out the most intense and long-track tornadoes are usually generated by supercells. And these stronger tornadoes usually become deadly.

Refresh Your Wardrobe with the Nordstrom Spring Dress Sale (SPONSORED)

From 2000 through 2019, EF2 or stronger tornadoes made up only about 10 percent of all tornadoes in the U.S., yet this small number of stronger tornadoes accounted for 95% of all tornado fatalities.

A 2019 study of 16,000 tornadoes over 15 years found 87 percent of deadly tornadoes were warned ahead of time and almost 95 percent of tornado deaths took place in an area under a tornado warning at the time.

"For EF2 strength or greater, our average (tornado) warning lead times are around 14 minutes," said Greg Schoor, National Weather Service (NWS) severe weather program manager, in an email to weather.com.

So the most destructive and deadly tornadoes are usually detected and warned ahead of time.

But there are many more difficult cases that can challenge even the most experienced meteorologist.

Some of these more challenging scenarios were laid out in a December 2020 study by Alexandra Anderson-Frey of the University of Washington and Harold Brooks from the NSSL.

1. A Select Few Supercells Spawn Tornadoes

There's an asterisk with supercells.

As few as 20 percent of supercells spawn tornadoes, according to the NSSL. It's still an active area of research to determine why one supercell becomes tornadic while most others do not.

Consider the St. Patrick's 2021 outbreak.

A supercell tracked directly over Tuscaloosa, Alabama, that afternoon. It exhibited an appendage on radar somewhat similar to a hook echo usually associated with a tornado, along with decent rotation, and a tornado warning was issued.

Yet this cell did not spawn a tornado over the city.

At the same time, another supercell to its east had a history of spawning multiple tornadoes.

The following day, a rotating thunderstorm prompted tornado warnings for parts of the Charlotte, North Carolina, metro area, yet all that occurred were some photogenic, rotating wall clouds.

Understandably, the NWS mentioned in the tweet below, they "can't take a chance with rotation like this" regarding the issuance of the tornado warning for the Charlotte metro area that afternoon.

2. Nighttime Tornadoes

Nighttime tornadoes are more than twice as likely to be deadly and make up a significant fraction of all tornadoes in a number of states from Oklahoma to Georgia to West Virginia.

Sometimes, nighttime tornadoes show up distinctly in radar data, as was the case in the deadly Fultondale, Alabama, tornado on Jan. 25, 2021.

But the lack of storm spotters and people still awake late at night cuts the amount of ground truth, or verification of a tornado in progress, available to the NWS.

"We do our best to guard against letting lack of confirmation influence us too much at night since lack of ability to view any tornado and low population density can be challenges," said Chad Omitt, warning coordination meteorologist at the NWS office in Topeka, Kansas, in an email to weather.com.

Omitt said forecasters also wrestle with whether the environment is still supportive for tornadoes once the sun sets.

"Nocturnal severe weather environments can be trickier to analyze, since a nocturnal inversion may develop and this makes it harder to determine whether surface-based storms can form or be sustained."

If this cool air near the ground is deep enough, it can inhibit tornadoes from forming and even prevent a thunderstorm's most destructive winds from reaching the ground.

Storm damage is seen after a tornado struck Brunswick County, North Carolina, early Tuesday, Feb. 16, 2021.

Storm damage is seen after a tornado struck Brunswick County, North Carolina, early Tuesday, Feb. 16, 2021.3. Summer Tornadoes

The Anderson-Frey and Brooks study also suggested tornadoes in the summer are trickier to detect ahead of time and false-alarm rates for tornado warnings were higher in the summer than other times of the year.

This may seem counterintuitive.

Summer is the hottest, often muggiest time of year. So it would seem there's ample heat and humidity to fuel thunderstorms.

While the summer months are the typical peak time of year for tornadoes in the Northeast, upper Midwest and Northern Plains, it's not just about heat and humidity.

As the jet stream migrates northward toward Canada in the summer, the magnitude of wind shear to support supercell thunderstorms - which, as we mentioned earlier, spawn the majority of tornadoes - often isn't there.

This can make it more challenging to be certain of a tornado in a more marginal environment.

When summer wind shear is higher, however, tornadic supercells can certainly occur in mid-summer in the northern U.S., as was the case in July 2020 in northwestern Minnesota.

4. Tornadoes Embedded in Squall Lines

Roughly 20% of tornadoes happen in lines of thunderstorms known as quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS), also known as squall lines, according to the NSSL.

For many reasons, this is one of the toughest challenges for issuing tornado warnings.

"They tend to form and dissipate quickly, making them difficult to pinpoint and warn based on radar alone," said Anderson-Frey in an email to weather.com.

These tornadoes will often show up as a subtle kink or notch in the line, hence the name "quasi-linear" to describe the wavy nature of these "lines" of thunderstorms.

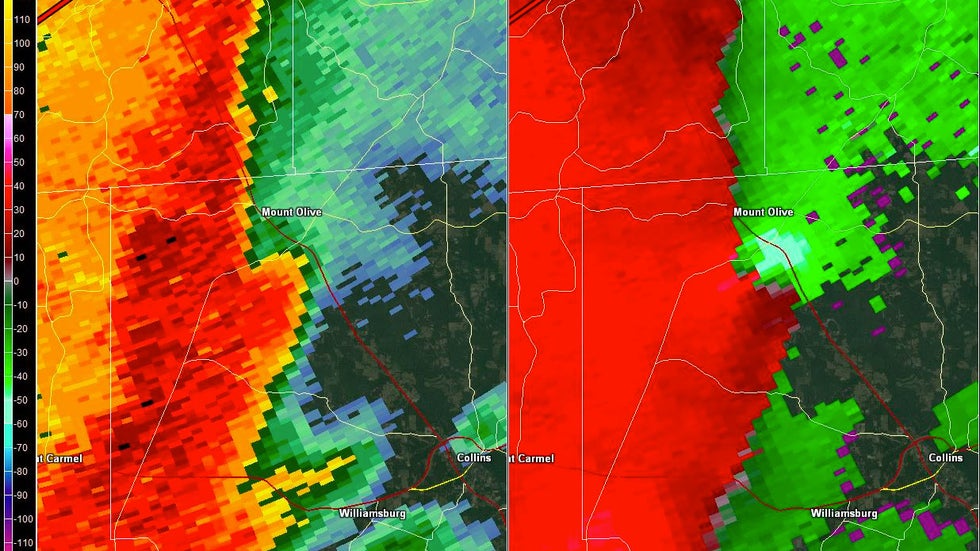

Radar reflectivity (left) and Doppler velocity (right) showing a tornado embedded in a squall line near Mt. Olive, Mississippi, on Jan. 2, 2017.

Radar reflectivity (left) and Doppler velocity (right) showing a tornado embedded in a squall line near Mt. Olive, Mississippi, on Jan. 2, 2017."There may be heightened risk at the end of a line (of thunderstorms), but it's harder to identify much in advance exactly where along the line a tornado may form."

Furthermore, that line of severe thunderstorms may move rapidly, and thus, so may the embedded tornado, offering little advanced notice even when a warning is issued.

Since they're embedded in squall lines, a tornado may be wrapped in rain and hard to distinguish from a shaft of heavy rain or hail. One example of a rain-wrapped tornado - though from a supercell thunderstorm - not a squall line, is shown in the tweet below.

Sometimes, the NWS will mention the potential for "short-lived embedded tornadoes" when issuing severe thunderstorm or tornado warnings well ahead of a QLCS/squall line.

While most tornadoes embedded in QLCSs are weaker and shorter-lived, that's not always the case.

The May 25, 2019, El Reno, Oklahoma, nighttime tornado was embedded in a squall line but produced EF3 damage.

5. Tornadoes in Unusual Places

Areas with relatively few tornadoes or severe thunderstorms present their own challenges when that rare event occurs.

"These environments may not have very many historical analogs in a particular area, making it harder to recognize a specific tornado threat," Anderson-Frey told weather.com.

"If these environments have previously spawned weak tornadoes, in regions like Washington state where there are large swaths of low-population-density regions or poor radar coverage, there may not have been confirmation on the ground."

One such example happened just after the St. Patrick's 2021 outbreak.

On March 19, a number of small thunderstorms pushed ashore along the Washington coast, prompting several tornado warnings from the NWS office in Seattle.

The rotation detected in Doppler velocity wasn't near the magnitude you might see in supercells in the Deep South or Plains, but it certainly was there. Click on the tweet below to see one example.

In this case, the NWS office in Portland, Oregon, was able to confirm an EF0 tornado near Ilwaco, Washington.

Anderson-Frey's research group is looking into ways to better understand these infrequent tornado environments using methods such as machine-learning techniques.

Take Every Warning Seriously

As you can see, there are many scenarios in which tornado warnings are issued without knowing with certainty whether a tornado is either happening or will happen.

"We aim to issue tornado warnings before the tornado touches down," said Greg Schoor, an NWS severe weather program manager.

It's this advance notice that's critical and ingrained in NWS warning policy.

"We do not wait (to issue a tornado warning) until we either receive a report or forecasters are confident from radar data that a tornado has touched down and is causing damage."

Layered on top of that uncertainty is the exceedingly small chance of direct impact.

"Even if a tornado occurs during a warning, it will cover such a small swath that the vast majority of people in the region of that warning are not likely to actually see one," said Anderson-Frey.

This is a long-standing problem facing meteorologists and social scientists. How do you get people to heed warnings in a high-impact but low-probability event?

"The challenge with weather warnings and tornado warnings specifically is that we need to ensure that the warning message provided speaks with enough certainty to facilitate action taking while also providing some context of the risk," Omitt told weather.com.

The bottom line is to take every warning seriously and act immediately.

If a tornado warning is issued, a professional meteorologist at your local NWS office has reason to believe a tornado may soon occur or is already occurring within a given thunderstorm.

"Tornadoes are erratic and evolve too quickly for NWS forecasters to take chances on what they may or may not eventually do," Schorr told weather.com.

"We will always err on the side of caution and want people in the warning to take immediate sheltering actions, even if you are on the far side of a warning and basically 'waiting' for it to approach your area."

And prior to severe weather, make sure you know where to take shelter and have multiple ways of receiving watches and warnings, including smartphones (and apps like The Weather Channel), NOAA weather radio, TV or radio.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment