Tom Niziol

Great Lakes ice cover has rapidly developed over the last week as frigid arctic air finally made its appearance.

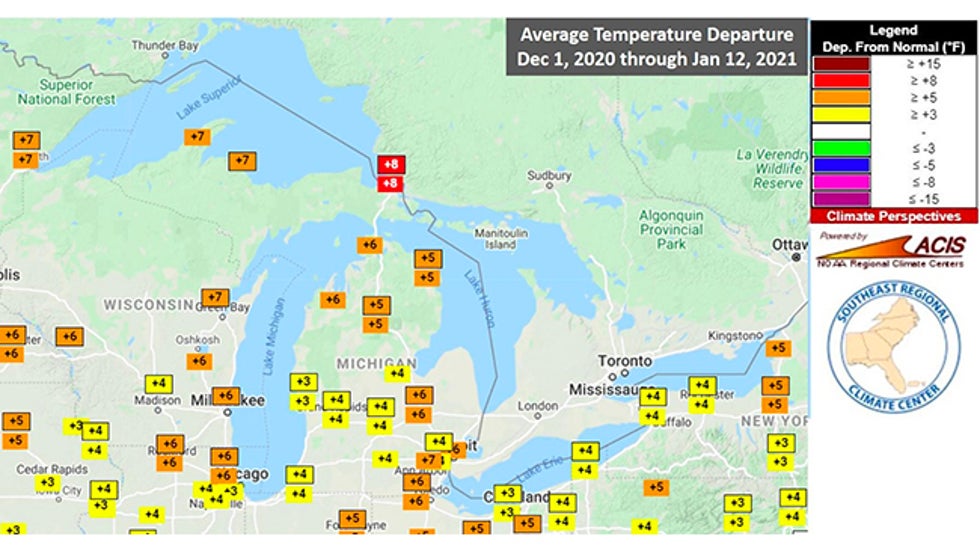

Up until very recently, the Great Lakes were experiencing one of the mildest winters on record. Through the middle of January, the average temperatures for the Great Lakes Region had been running 4 to 8 degrees above average.

That warmth kept the Great Lakes from chilling down as they usually do at this time of the year.

Temperature departures from average from Dec. 1, 2020, through Jan. 12, 2021. The entire Great Lakes region was much warmer than average through the period.

Temperature departures from average from Dec. 1, 2020, through Jan. 12, 2021. The entire Great Lakes region was much warmer than average through the period.That all changed over the last week or so as an Arctic air mass blanketed the entire region.

Temperatures across the Great Lakes region, over the five-day period from Feb. 5-9, were a bone-numbing 8 to 17 degrees below average, a “polar opposite” of how the year began.

Great Lakes water temperatures and subsequent ice cover respond most directly to the regional temperatures. If it gets cold, so do the lakes, albeit at a slower pace because that volume of water responds more slowly to those air temperature changes.

Those frigid conditions, however, have turned on the ice-making machine in earnest.

The weekly percentage of Great Lakes ice coverage (blue bars) from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 5, 2021, compared to the 1980-2010 average (light green line). Ice coverage nearly doubled in just one week from late January into early February.

The weekly percentage of Great Lakes ice coverage (blue bars) from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 5, 2021, compared to the 1980-2010 average (light green line). Ice coverage nearly doubled in just one week from late January into early February.On a seasonal basis, the past few weeks typically see the greatest build-up in ice coverage over the Great Lakes.

Animation showing the average ice concentration by week through the winter over the Great Lakes, with ice concentration indicated by the color legend.

Animation showing the average ice concentration by week through the winter over the Great Lakes, with ice concentration indicated by the color legend.More typically cold winter temperatures since the last half of January allowed Great Lakes water temperatures to gradually drop to near the freezing point. Then, the arctic outbreak kicked everything into high gear.

The past week has seen significant ice growth, nowhere more apparent than on Lake Erie, the shallowest of all of the Great Lakes.

Its ratio of the surface area the lake covers to its meager volume allows it to respond much more quickly and ramp up ice growth in comparison to the other Great Lakes.

Visible satellite images taken on Feb. 3 (first image), and Feb. 9, 2021 (second image) illustrating the rapid growth of ice cover on Lake Erie.

Visible satellite images taken on Feb. 3 (first image), and Feb. 9, 2021 (second image) illustrating the rapid growth of ice cover on Lake Erie.As the graph below shows, Lake Erie typically sees its greatest ice growth from the beginning of January, peaking sometime in mid-February. I think Lake Erie was a late bloomer this winter, but it sure has made up for it lately.

Lake Erie ice coverage, in percent, so far in 2020-21 (red line) compared to the average from 1973-2020 (thick blue line).

Lake Erie ice coverage, in percent, so far in 2020-21 (red line) compared to the average from 1973-2020 (thick blue line).The increase in ice cover is welcome news to some recreationists, in particular for those who ice fish. It means they can finally get out on the ice pack to one of the many outdoor activities that winter brings to the region.

Another result of rapid ice cover on Lake Erie is the decrease in major lake-effect snow events because there is not as much open water to spawn those storms. Lake-effect snow is still possible but typically is dialed down somewhat when there is a lot of ice on a lake.

Most of the other Great Lakes, however, are still wide open and that means lake-effect snow is still likely to add to the snowpack in places like Marquette, Michigan, which is running a nearly 4-foot snowfall deficit for the season (46 inches).

With the latest 8- to 14-day temperature probability forecast from NOAA calling for average to below-average temperatures across the Great Lakes, it looks like Mother Nature will continue to add "icing" to this "cake."

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment