Jonathan Belles

As a reminder that there is one month left in this hurricane season, we're watching for yet another tropical depression or storm in the Caribbean next week. It could bring significant heavy rainfall and gusty winds to Central America at the beginning of November.

This tropical threat comes from a late-season tropical wave swiftly moving westward through the Caribbean Sea.

What We Know Right Now

The tropical wave, dubbed Invest 96L by the National Hurricane Center, has a high chance of development. It is likely to become the season's next tropical depression or storm this weekend or early next week in the central or western Caribbean.

(MORE: What Is an Invest?)

It is bringing showers and thunderstorms to Hispaniola and the ABC Islands (Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao).

This system will move westward through at least Tuesday with a gradually decreasing forward speed as it reaches the western Caribbean.

Chance of Tropical Formation in the Caribbean

Chance of Tropical Formation in the CaribbeanThis wave is moving into the warmest water temperatures in the Atlantic Basin, surpassing 85 degrees at times in the expected path of this system. This is still very supportive of tropical development and intensification.

Wind shear – the change in wind direction and wind speed, which typically keeps a lid on tropical storm and hurricane intensity – is expected to remain low.

These two favorable ingredients for development could allow this system to become a tropical storm this weekend or early next week. It could go beyond that and become a hurricane next week, but this is somewhat uncertain. When this system becomes a tropical storm, it will be named "Eta," the first unused greek letter in the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season.

Regardless of development, this system will produce heavy rain and possible flooding in Central America, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands through next Friday.

More than a foot of rainfall is possible in parts of Central America, but this forecast will be refined over the weekend.

Gusty winds are also likely if this system nears Honduras or Nicaragua, but these details will need to be adjusted in the days to come.

What We're Figuring Out

After Tuesday, the track forecast is much more uncertain.

Many computer models show whatever this system becomes meandering near Nicaragua and Honduras during the middle of the upcoming week.

At that time, the system will interact with a high-pressure system, or a ridge or dome of higher pressure, which should be located over Mexico, the eastern Pacific and/or the Gulf of Mexico.

That ridge should guide the tropical system, but both the location of this ridge and its strength are uncertain.

There are at least two possible scenarios that could unfold toward the end of next week:

- If the ridge is farther north or weaker, the system could cross Central America and escape into the eastern Pacific Ocean.

- If the ridge is farther south or stronger, it could get stuck near Central America or recurved north or northeastward.

Neither solution is slightly more likely than the other at this time.

The Hurricane Hunters may fly out to this system on Sunday afternoon to help this forecast improve.

November in the Tropics

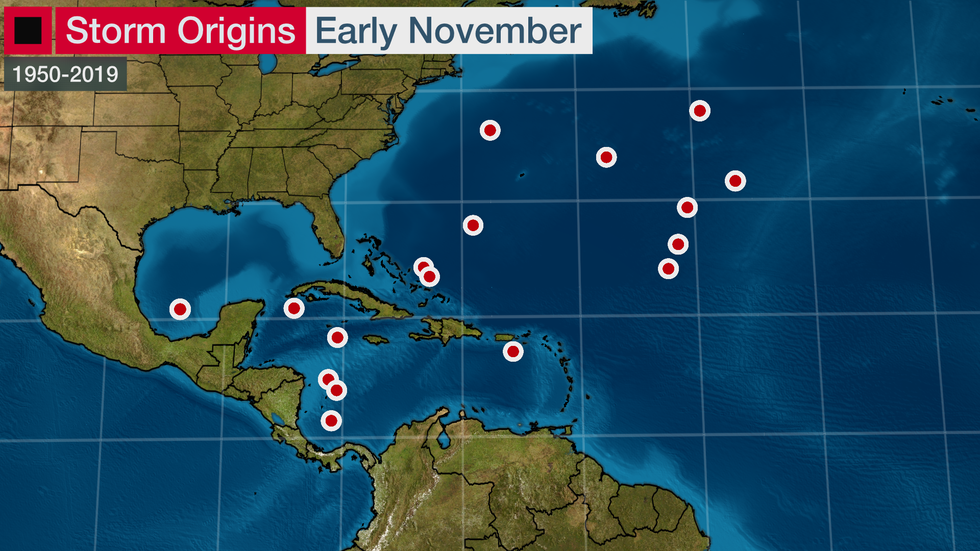

Tropical development isn't all that unusual in the western Caribbean in early November.

In fact, several storms have formed in this area over the last 70 years.

Notably, hurricanes Paloma (2008) and Michelle (2001) have formed near Central America and then moved northeastward toward Cuba. Paloma intensified to a Category 4 near Cuba before weakening to a Category 2 at landfall in the country, causing heavy damage in both Cuba and the Cayman Islands. Michelle was one of the most significant hurricanes in Cuban history at the time, causing billions in damage as a Category 4 hurricane.

We should expect one named storm every other November, and one November hurricane roughly every three years. Of course, some years are more active than this while others are quieter.

Historically, most systems that form in the western Caribbean are scooped up by the dipping jet stream over the United States and pushed northeastward over Cuba and the Bahamas and out to sea.

Other tropical systems form in the open Atlantic and around Bermuda or the western Atlantic. These systems are typically spawned by drooping cold fronts in that region or other orphaned low-pressure systems that break off from the jet stream.

By the end of the month, this jet stream makes it increasingly inhospitable for tropical systems to form in the Gulf of Mexico and the western Atlantic. Water temperatures increasingly get too cold for tropical development elsewhere in the basin, leading to less frequent systems.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment