By AccuWeather meteorologist and staff writer

Published Sep. 30, 2020 12:39 PM

As Americans hunker down to weather the pandemic this winter at home, nearly every facet of life will remain upended to safeguard against the coronavirus. Millions are working from home and learning remotely and even holiday gatherings will look a lot different this year. Staying closer to home may mean fewer weather worries for commutes and disruptions to daily activities, but AccuWeather has you covered on what you can expect weather-wise as we navigate uncertain times.

Accuweather’s team of long-range forecasters, led by Senior Meteorologist Paul Pastelok, released its annual predictions for the upcoming winter season this week. The team has been analyzing global weather patterns and various weather models to project what conditions will unfold across the lower 48 United States this winter, which arrives on Dec. 21 this year. Much of the time the setup will be driven by one key factor: La Niña.

La Niña is a phenomenon in which the surface water near the equator of the Pacific Ocean are cooler than normal, the opposite of El Niño when the water in the equatorial Pacific is in a warm phase. This change in the water temperature can have a major influence on the weather patterns all around the globe. According to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, La Niña officially developed by early September and is forecast to continue through the winter months.

The ongoing La Niña is projected to bring weather conditions similar to what meteorologists expect across the country during a typical La Niña pattern, but there may be a few subtle differences, Pastelok said.

Take a look below at a complete region-by-region breakdown:

Northeast, Midwest

The winter of 2019-2020 was tame across much of the northeastern U.S. with only a handful of Arctic outbreaks and very little snow to speak of along the Interstate 95 corridor -- and the upcoming winter could bring some echoes of last winter.

“Another overall mild winter is possible for much of the eastern U.S.," Pastelok said, referring how temperatures will compare to the 30-year averages in many places. However, he expects "near-normal snowfall across much of New England.”

And, it's worth noting, the entire season will not be mild all the way through. Instead, the season will be bookended by cold and snowy conditions with a pause in the wintry weather in the middle of the season.

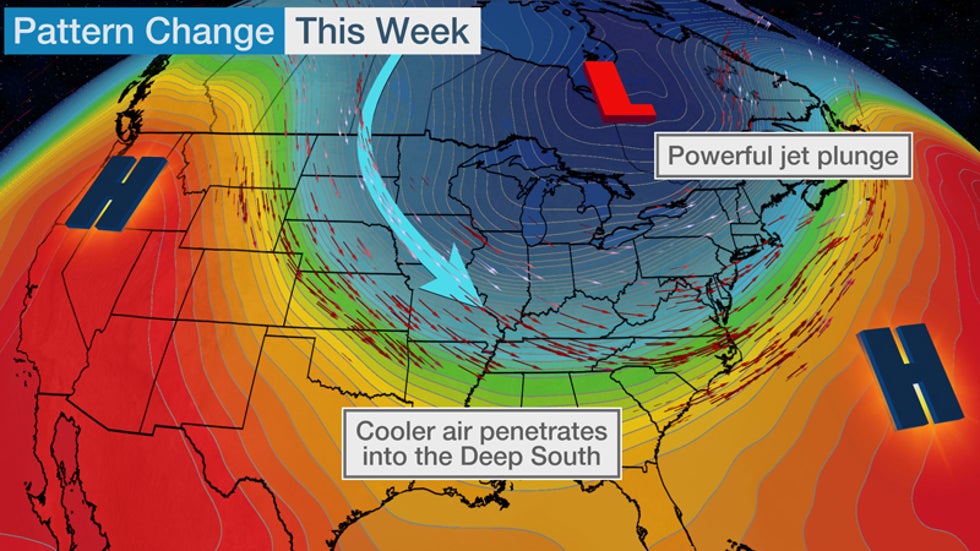

“An early-season chill is expected in the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley into the Northeast,” Pastelok said.

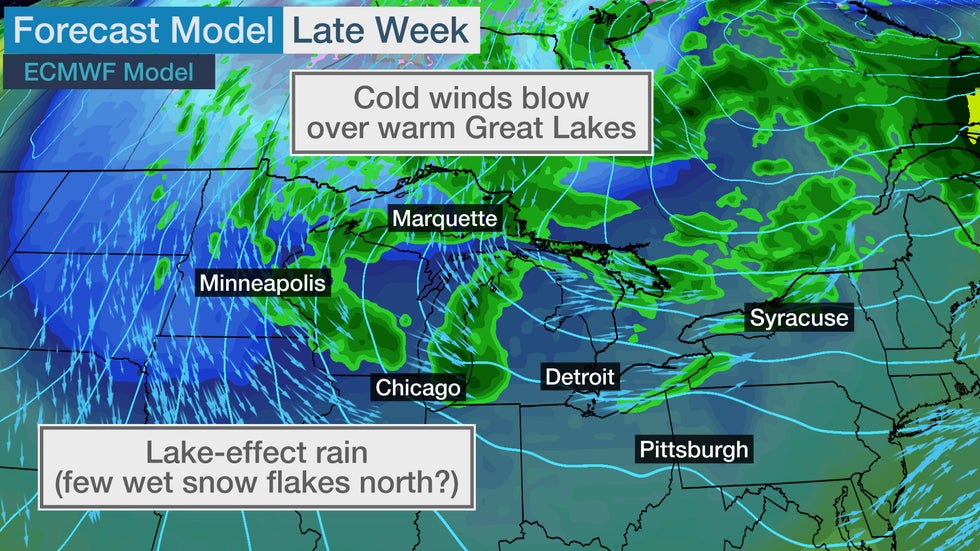

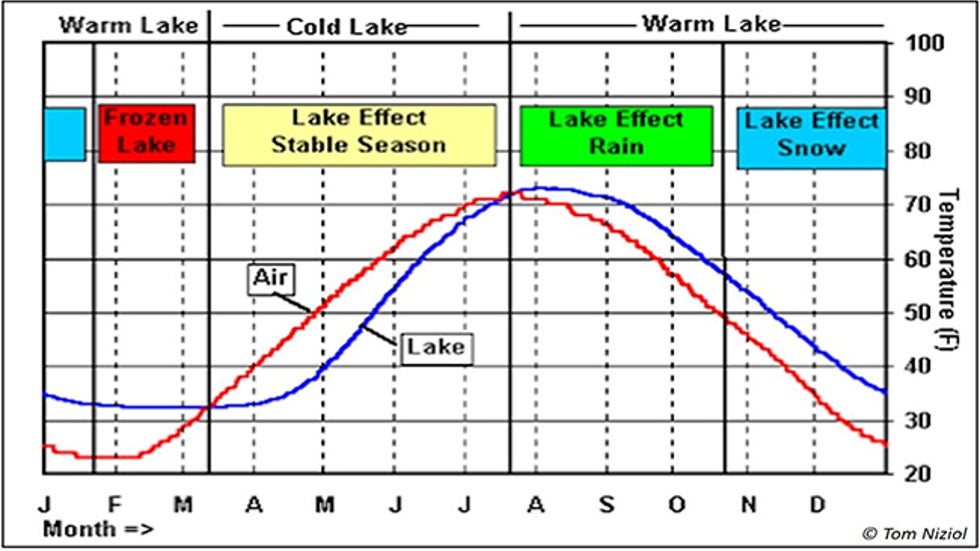

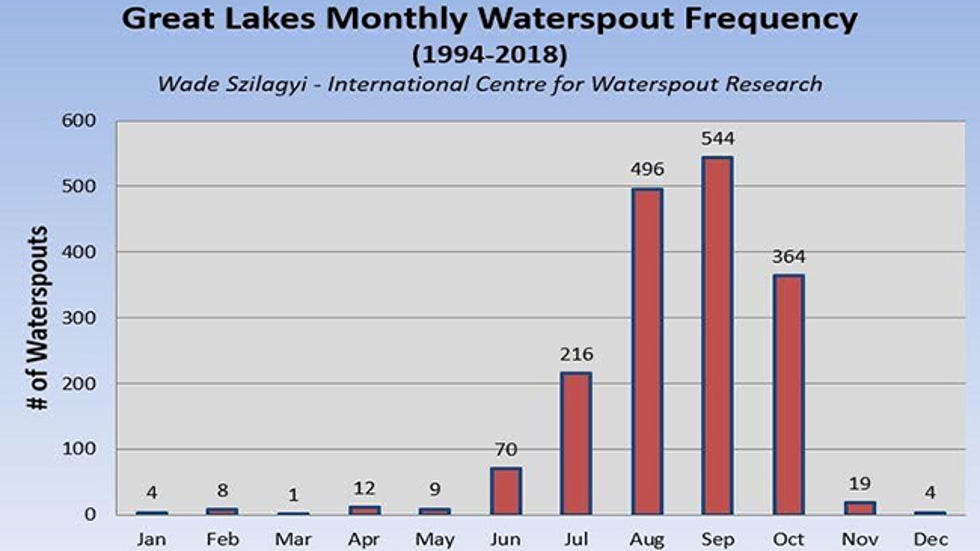

The first waves of chilly Arctic air will set off rounds of lake-effect snow downwind of the Great Lakes, as well as bring opportunities for snow in some of the bigger cities across the region heading into the holiday season.

“There is a good chance for a white Christmas in Chicago, perhaps around 30-35% chance at this point,” Pastelok said. “For Pittsburgh, much of the lake-effect snow could fall north of the city and it may be tough to keep snow on the ground. But from this far out I give a 15-20% chance for a white Christmas in Pittsburgh, but, still, there is a chance.”

Christmas trees laden with freshly fallen snow are displayed for sale at Boston Hill Farm, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2019, in North Andover, Mass. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola)

After the calendar flips to 2021, Old Man Winter will eventually loosen his grip on the region.

“A big turn" is expected around the middle of the season as temperatures are predicted to rise and snowfall should decrease, Pastelok said, due in part to the strength and positioning of the polar vortex. More on that later.

But as the Northeast sees a break in the cold and snow, folks across the Great Lakes and Midwest will want to brace for some bitter spells of wintry weather.

There will be a favorable storm track mid-season for the Midwest and Great Lakes, leading to above-normal precipitation and a few heavy snowfalls events, Pastelok explained.

The storm track will eventually shift eastward during the latter part of the season, bringing the potential for some big coastal snowstorms.

A woman shovels a yard during a snowstorm, Thursday, Jan. 4, 2018, in Ocean Grove, N.J. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

A period of stormy and snowy weather may occur later in February or March as nor'easters can develop and impact the region, Pastelok cautioned.

Even with the potential for some big snow events, the season as a whole is forecast to finish with near- to- below-average snowfall for much of the Northeast and Ohio Valley. In contrast, the Upper Midwest could pick up near- to- above-normal snowfall. Winter storms could dish out a whopping 55 to 65 inches of snowfall this season in Minneapolis, which sees 54.7 inches of snow on average based on data from 1991 to 2020.

Southeast

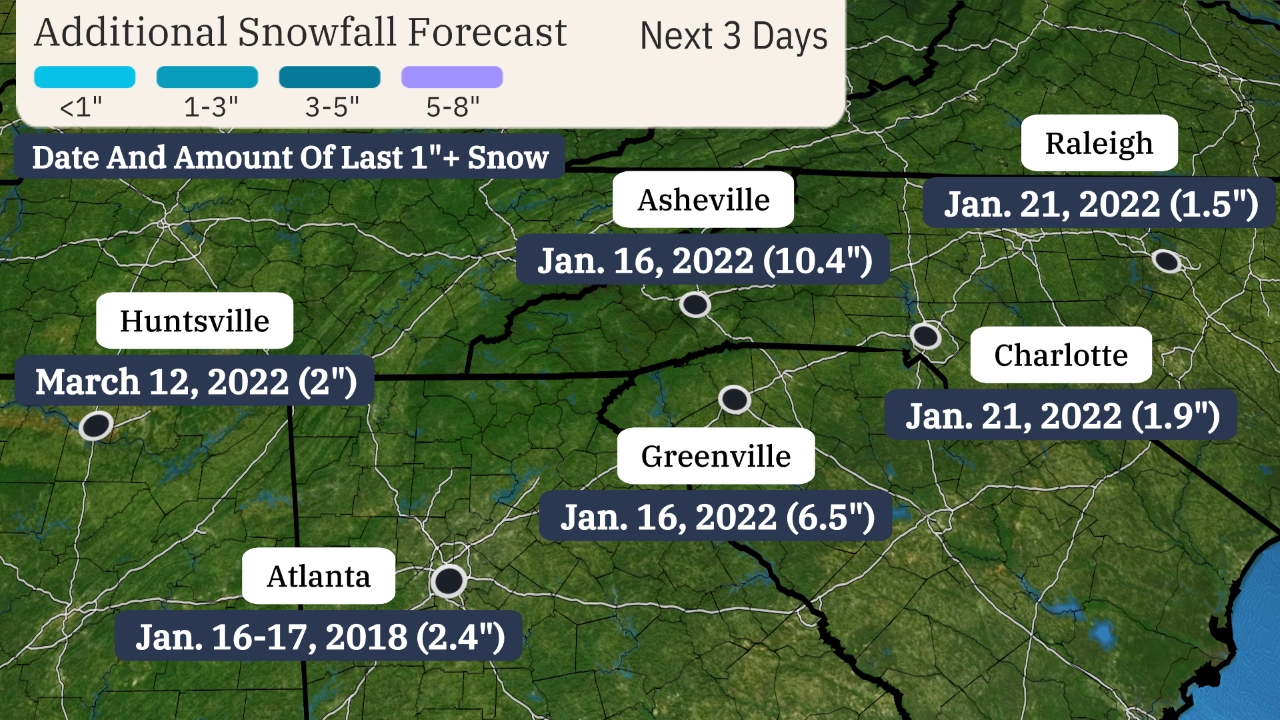

The first part of the winter may be the coldest for the southeastern U.S., as a brief shot or two of cold air has the potential to rush down from the north all the way to the Gulf Coast.

“Early cold may take a run at the eastern U.S. if snow lays in the Ohio Valley and parts of the Tennessee Valley in December,” Pastelok said.

Atlanta, Huntsville, Alabama, Greeneville, South Carolina, and Charlotte and Raleigh, North Carolina, could all be hit by a cold snap to kick off the season. Even Floridians may want to make sure to dig out heavier coats from the closet sooner rather than later.

“There is a small chance for an early-season frost in northern and central Florida perhaps impacting the citrus crop,” Pastelok added.

Temperatures are projected to rebound as the season carries on, paving the way for much warmer conditions through the balance of the winter.

“Near-record warmth [is predicted] at times in the Southeast, occasionally extending into the mid-Atlantic,” Pastelok said.

This extended warmth will be good news for restaurants across the region that have added outdoor seating areas due to the coronavirus pandemic, and could perhaps allow them to utilize the extra space even during the winter months.

Restaurants that do have outdoor seating should still keep a close eye on the weather forecast, not just for temperatures, but also for disruptive storms, especially during the first few weeks of 2021.

Empty outdoor seating for a restaurant and closed hotels are shown, Tuesday, Aug. 11, 2020, in Miami Beach, Florida's famed Ocean Drive on South Beach. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

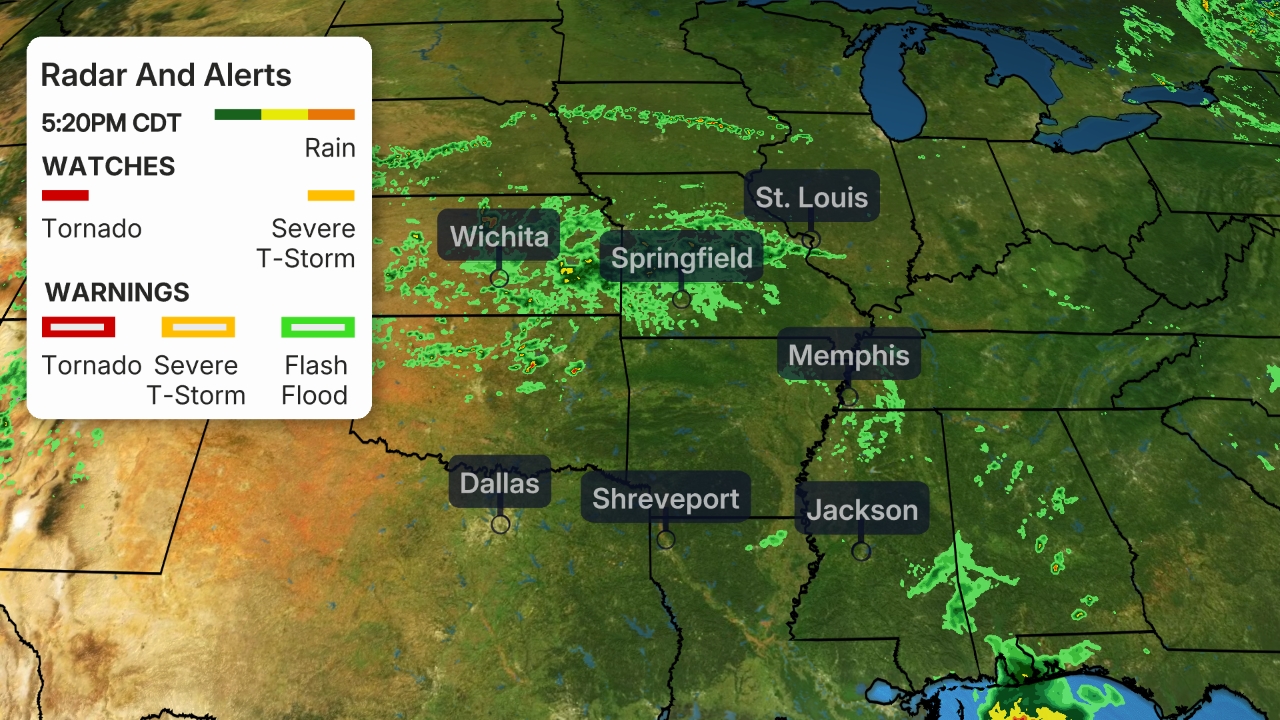

“Severe thunderstorms may occur more than usual from the central Gulf Coast to the Southeast in late January and February,” Pastelok said.

Storms could not only spoil an outdoor meal but also bring gusty winds that could damage some of the temporary structures that have been constructed to keep patrons safe from the spread of the new coronavirus.

Plains, Rocky Mountains

The central U.S. experienced a taste of winter as soon as autumn arrived. Meteorological fall began on the first day of September, and just one week later, a winter-like storm dove down across the Plains and northern Rockies, causing temperatures to tumble and delivering snow to the Rockies and some of the foothills. Denver saw the temperature go from a high of 93 one day in early September, to a low of 36 and snowfall the next day.

It may have been a shock to the system for people who live from Montana to New Mexico, but it was a preview of what is to come this winter.

“The middle of the nation may go through some big swings in temperatures, [and] dry and active periods,” Pastelok said. “Periods of subzero cold can drive south down the Front Range of the Rockies, the central and western Plains.”

CLICK HERE FOR THE FREE ACCUWEATHER APP

Snow will be a prominent feature during these big swings, especially over the northern Rockies and into parts of Colorado, which will be beneficial for ski resorts across the region.

“Montana, Utah, Wyoming, and especially the west slopes of Colorado can do quite well” in terms of snowfall, Pastelok said.

There is also the chance for some frequent snowfall in the northern Plains in parts of Nebraska, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota.

Farther south, the chances for snow will be lower, including part of the southern Plains, the southern Rockies and westward into the Four Corners.

Meanwhile, the central Plains will be in the battleground zone, swinging from bitterly cold conditions to spells of milder weather and then back again in less than a week’s time.

While skiers in the mountains hope for snow to fall early and often, so too will some farmers across the Plains, especially in Kansas, western Oklahoma, and the Texas Panhandle, a major crop area for winter wheat, according to the USDA.

“If there is a lack of snowpack, this can endanger the winter wheat crop,” Pastelok said.

A lack of snow may compound the drought concerns for farmers across the region that could carry over into next year.

Farther west over the Four Corners and into Nevada where drought conditions are even worse, the lower frequency of storms will translate to longer-term drought issues.

According to the United States Drought Monitor, parts of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and far western Texas are already enduring extreme drought conditions. Some smaller areas are in the grips of exceptional drought conditions, the worst level of drought highlighted by the drought monitor report. Even in the spring when snow in the mountains melts and helps to fill rivers, a below-average snowpack would leave rivers at lower levels.

West Coast

Autumn may feel shorter this year across the Pacific Northwest as wintry weather makes an early entrance across the region.

“Mountain snow and stormy conditions may arrive in late fall for the Northwest, northern California and northern Rockies,” Pastelok said.

Even the Interstate 5 corridor from Medford, Oregon, through Seattle will have several opportunities for accumulating snowfall, potentially even before 2020 draws to a close.

“It may not just be the Cascades that get hit, but interior Northwest areas, even down through Wasatch Mountains central Rockies and northwest Wyoming as well,” Pastelok added.

The waves of storms throughout the upcoming months will help to ease the drought conditions across the region, especially in Oregon where more than 60% of the state is in severe drought and over 30% is in an extreme drought.

More importantly, the early arrival of winter storms will spell the conclusion to a historic wildfire season that has charred millions of acres across Washington, Oregon and California.

However, after the flames have smoldered, heavy rains could pose an added danger in the burn scars left behind by the fires, especially in the mountainous terrain.

With a lack of healthy vegetation and root systems in place, the charred landscape is more susceptible to flooding and can quickly lead to flash floods and mudslides. In some cases, it can take years for vegetation to become reestablished to bring down the risk of flash flooding near burn scars.

In this photo provided by Santa Barbara County Fire Department, mudflow, boulders, and debris from heavy rain runoff from early Tuesday reached the roof of a single story home in Montecito, Calif., on Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2018. A storm caused deadly mudslides in fire-scarred areas of Montecito and adjacent Santa Barbara County. (Mike Eliason/Santa Barbara County Fire Department via AP)

An onslaught of storms tracking over the Pacific Northwest follows the typical trend of winter during La Niña, and the same can be said for the projected weather pattern across the southwestern U.S.

“We are not looking at any active track into Southern California this winter, just occasional rain events may reach these areas in January and February,” Pastelok said.

Similar to the Southeast, restaurants and bars across Southern California, Arizona and into southern Nevada that have constructed new outdoor seating areas amid the pandemic may benefit from the mild and dry pattern.

This is especially true in cities like Phoenix, which this year experienced a record-setting number of days where the temperature reached 110 F, where the heat could be too uncomfortable for outdoor dining.

A dry winter could also be good news for families looking to take a winter vacation to one of the many national parks across the region. People who had to cancel trips earlier in the year because of coronavirus-related restrictions or air quality concerns due to smoke from the large wildfires across the region may find some cooperative weather to travel through parts of the Southwest this winter.

What about the polar vortex?

Earlier this year, the polar vortex dipped down over northeastern Canada in April, causing Easter in many parts of the U.S. to look more like Christmas. What's in store for the dreaded weather maker this coming winter? "We expect the polar vortex to strengthen again in the middle of the season this year," Pastolek said, explaining that a strong polar vortex means the brutally cold Arctic air associated with it remains locked in place over the North Pole region. He said, however, that the strengthening will "probably not be as strong and won't hold on as long as last year over the pole."

But if the polar vortex holds strong, that could spell milder conditions for a significant stretch across parts of the Eastern Seaboard, at least for part of the season. "A strong polar vortex around the pole mid-season would lead to a possible January thaw that could linger into February for the East," Pastelok said, expanding on what would drive the warmup for parts of the Northeast. "We are uncertain whether the vortex will play a role in the early cold shots in December, but it could have a brief role later in February or March."

Keep checking back on AccuWeather.com and stay tuned to the AccuWeather Network on DirecTV, Frontier and Verizon Fios.