As hurricane season ramps up, meteorologists begin to look farther east for tropical activity – all the way to Africa.

Tropical waves, often called African easterly waves, are the building blocks for much of the tropical storm and hurricane activity in the Atlantic and even Pacific basins. These are not waves in the ocean in the sense that you can play in them at the beach, but the ocean does play a large part in pumping moisture into these atmospheric waves, which exist from near-surface level to 10,000 feet above the ocean.

Usually these waves don't factor into tropical storms or hurricane development in the Atlantic until July or August, but already, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) took an interest in one of these waves earlier this week. That wave was dried out and sheared out before it got to the southern Windward Islands.

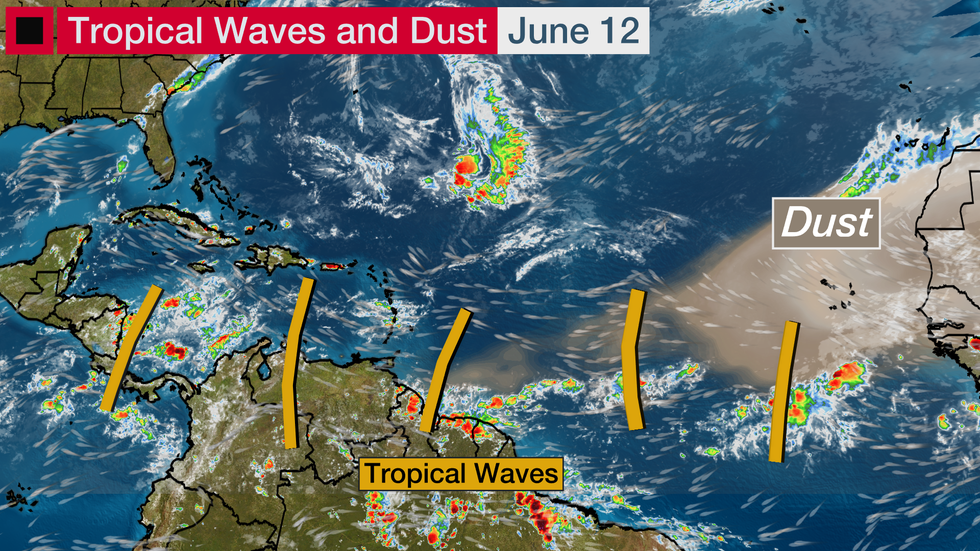

But the Atlantic remains active for this time of year, with five tropical waves being noted by the NHC as of Friday morning.

A Look at the Tropics

A Look at the TropicsWhile this wouldn't be notable in July or August, this number of "active" tropical waves is on the high side for June. Active tropical waves are those that produce thunderstorm activity.

One especially notable tropical wave is rolling westward just south of Cabo Verde near Africa on the graphic above.

None of these waves are expected to become tropical cyclones into next week, but they could be a sign of things to come.

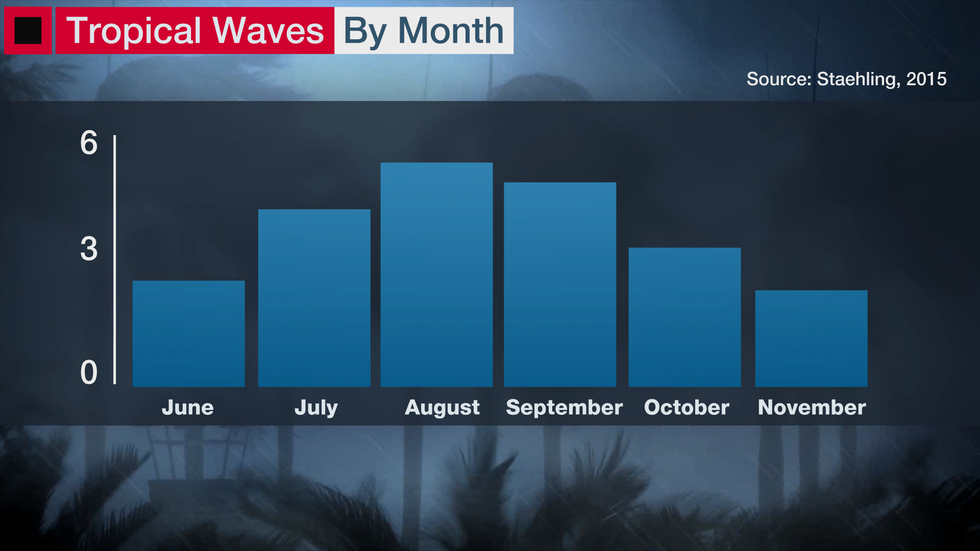

A recent extensive climatology, produced by Erica Staehling in doctoral research at Princeton University, compared studies over the last few decades. All of these studies agreed that tropical wave activity peaks in August and September.

The number of robust tropical waves produced by month in the Atlantic Basin.

The number of robust tropical waves produced by month in the Atlantic Basin.With several tropical waves already moving westward across the Atlantic and Caribbean, it could be at least one sign that an active hurricane season is ahead.

The higher number of tropical waves so far this year may be due to a wetter-than-average Sahel region in Africa. As explained in the next section, that region provides one part of the temperature and moisture contrast that helps create tropical waves.

This extra moisture makes it easier for tropical waves to form, and then succeed in their voyage across the Atlantic if they can maintain their moisture. The extra moisture can also limit the extent of the Saharan Air Layer, which often dries out tropical waves early and late in the season.

According to the National Hurricane Center, 60 tropical waves track across the Atlantic Ocean each year, including weaker tropical waves as well as the more robust ones studied by Staehling. Roughly one in five of these tropical waves becomes an Atlantic Basin tropical cyclone, and a few of these waves become tropical storms or hurricanes in the eastern Pacific.

Most hurricanes develop from these lines of showers that cross the Atlantic and can often be traced as far back as eastern Africa.

What Is a Tropical Wave?

The formation of a tropical wave can be traced back to Africa.

The formation of a tropical wave can be traced back to Africa.Tropical waves are batches of energy and spin in the atmosphere that develop due to temperature contrasts in northern Africa.

Like cold fronts in the United States that gain energy from contrasts between Canadian arctic air and warm Gulf of Mexico air, tropical waves thrive on energy provided by the contrast between deep, hot air over the Sahara Desert and milder, more humid air over forested areas of the Gulf of Guinea and central Africa. The contrast zone in between these regions is known as the Sahel.

The contrast across the Sahel between hotter and milder air increases during the summer months as the Sahara Desert heats up.

The frequency of tropical waves peaks in July when that contrast is the highest in western Africa. It's the time of year when about 10 tropical waves roll off the African continent per month.

Tropical waves can take a few weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean under the guidance from the Bermuda-Azores high.

Tropical waves can take a few weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean under the guidance from the Bermuda-Azores high.These waves journey westward across the Atlantic and Caribbean, aided by the constant push of the Bermuda-Azores High. It usually takes one to two weeks for waves to successfully cross the Atlantic, but many waves do not survive that trek.

The waves may or may not contain thunderstorm activity. In the early part of the hurricane season, easterly waves are often dry because they collect dry air from the Sahara Desert.

That dry air often pools in the eastern Atlantic and stretches to the eastern Caribbean islands, creating what is often referred to as the "Saharan Air Layer." That dry air can sometimes reach the Southeastern U.S., providing drier conditions and more colorful sunsets.

From July through September, tropical waves become more likely to contain thunderstorms and thus are more likely to become tropical storms and hurricanes.

Diagram showing tropical wave movement to the west. Africa is near the center of the diagram. Time progresses from top to bottom over a two-day period.

Diagram showing tropical wave movement to the west. Africa is near the center of the diagram. Time progresses from top to bottom over a two-day period.Tropical waves are tracked on satellite imagery through Africa and across the Atlantic using specialized "Hovmöller diagrams" (seen above) that make it easy to follow them from east to west.

(INTERACTIVE: Latest Africa Satellite Loop)

In a satellite image, a tropical wave with active thunderstorms often looks like an inverted "V," especially as it develops further. A small rain band may exist on the western side of a tropical wave, with a much stronger and broader band on the eastern side.

Tropical waves are watched by the NHC and can be investigated using specialized tropical models and satellite imagery. Development probability and the chance of tropical cyclone formation are diagnosed by the NHC every six hours during hurricane season. The percentages given in the NHC tropical weather outlooks tell you the odds that a tropical wave might develop into at least a tropical depression over the next 3 or 5 days.

(MORE: What is an 'Invest?')

Without a satellite loop, you may not know a tropical wave is approaching. Ahead of a mature tropical wave approaching the Caribbean islands, for instance, the weather is generally fine; falling surface barometric pressure would be your only clue, as air generally sinks ahead of a tropical wave.

The structure of a tropical wave.

The structure of a tropical wave.Once the wave axis passes – in other words, surface pressure bottoms out – winds shift out of the southeast and showers and thundershowers pick up.

In the early stages of a tropical wave over the eastern Atlantic, some clouds and showers can overlap over the wave axis. Generally speaking, however, the rain is on the eastern side of the tropical wave.

Tropical waves can bring flooding rains and gusty winds to the Caribbean islands and Central America. Tropical waves often move at 10 to 20 mph, but can move faster.

These waves need to survive dry air, fast upper-level winds and the elevated terrain of the Caribbean islands before they can impact the United States. Only tropical waves in near-ideal conditions can become hurricanes.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment