weather.com meteorologists

Weather records actually exist from July 4, 1776, Independence Day, and they were taken by one of America's Founding Fathers.

In 1776, weather observations were few and far between. Weather instruments were costly and most weather observers – those who kept weather diaries, at least – were wealthy. One of them, Thomas Jefferson, kept meticulous weather records in a journal for many years.

Jefferson traveled to Philadelphia at the beginning of July 1776 to attend a meeting of the Second Continental Congress and to prepare the Declaration of Independence.

He brought his thermometer on the trip, but while he was in Philadelphia, Jefferson purchased a new one from a merchant, John Sparhawk, for a sum equivalent to $500 today.

According to monticello.org., Thomas Jefferson liked to take at least two weather observations per day. One would happen around sunrise so he could log the low temperature of the day, and another was between 3 and 4 p.m. when the high temperature usually occurred. He would also list remarks like cloud cover, precipitation and whether or not it was humid.

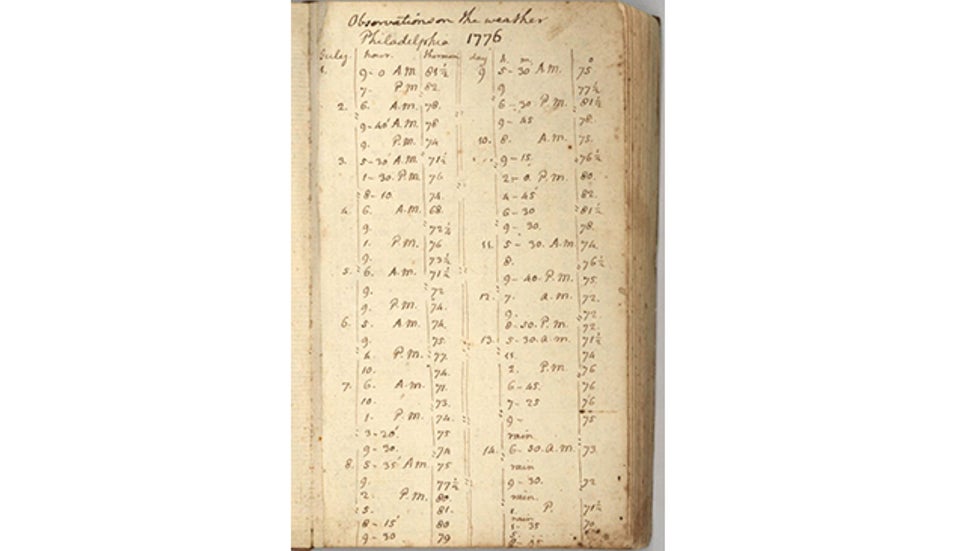

Here are Thomas Jefferson's daily weather observations taken in Philadelphia in July 1776.

Here are Thomas Jefferson's daily weather observations taken in Philadelphia in July 1776.According to a WxYz Weather World segment from Penn State University's Jon Nese, there was another prominent resident of Philadelphia, Phineas Pemberton, who logged daily weather conditions.

From these entries, we can formulate a picture of weather conditions during that first week of July.

According to these records, July 1 was warm and humid with temperatures well into the 80s. The day was mostly sunny, but at around 4 p.m., the sky turned dark, winds came up and thunderstorms developed around the area.

Temperatures came down a bit on July 2, but there were frequent showers reported. July 3 was a pleasant, sunny day, with a high near 80 degrees.

This is the typical sequence of events you might see today with a cold front passage in summer. Warm and humid, then thunderstorms, then cooler and pleasant after the cold front is gone.

Philadelphia's Weather On July 4, 1776

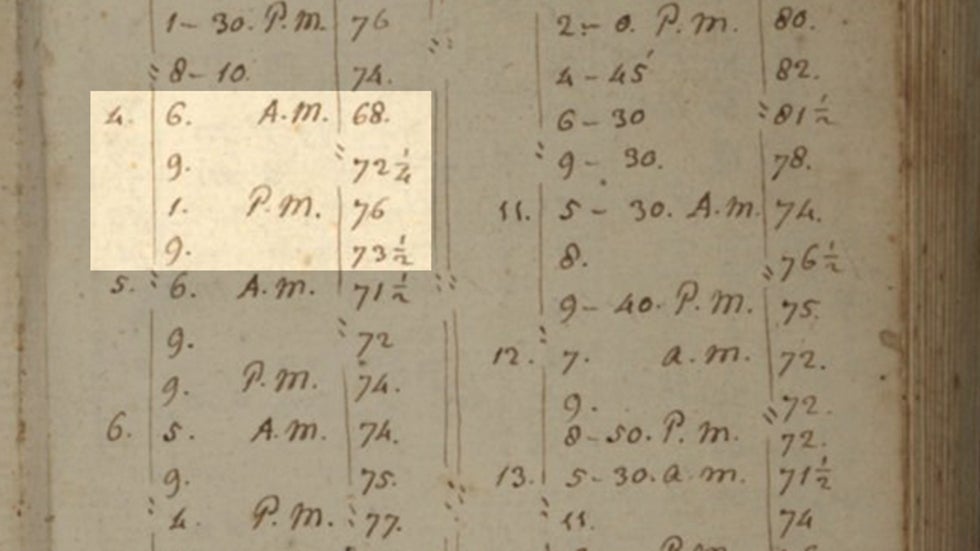

The observations from Jefferson on July 4, 1776, are shown below. Jefferson didn't record his usual 3-4 p.m. observation, but he did at 1 p.m. He had more pressing matters that day.

A zoomed-in photo of Thomas Jefferson's weather observations from July 1776. His July 4 observations are highlighted by the square, with the time of each observation at left and the temperature (degrees Fahrenheit) on the right.

A zoomed-in photo of Thomas Jefferson's weather observations from July 1776. His July 4 observations are highlighted by the square, with the time of each observation at left and the temperature (degrees Fahrenheit) on the right.These temperatures were fairly consistent with those noted by Pemberton, who recorded 71 degrees at 7 a.m. and 76 at 3 p.m.

Both Jefferson and Pemberton noted clear skies and a light north wind early in the morning, then increasing cloudiness with a southwest wind in the afternoon. No rain was mentioned by either.

This suggests that July 4, 1776, was a nice summer day in Philadelphia, particularly by modern standards.

Philadelphia's average July 4 high (based on 1991 through 2020 data) is 87 degrees, though summer temperatures have warmed considerably since 1970.

And given the early morning temperature was in the upper 60s or low 70s with a light north wind, it probably wasn't very muggy by July standards for the mid-Atlantic.

What The Weather Map Probably Looked Like

There were no hourly, much less daily, weather maps produced in the U.S. in 1776. It would be another 94 years before the invention of the telegraph and the launch of what would much later become the National Weather Service allowed weather observations to be collected and disseminated from multiple areas at one time.

(IN DEPTH: The History Of The National Weather Service)

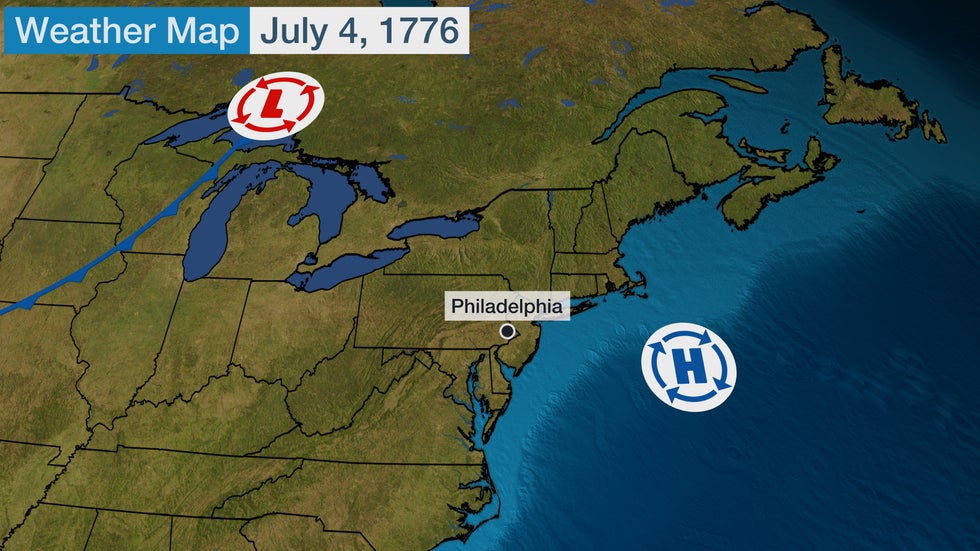

But given the observations from Jefferson and Pemberton, we can form a fairly good guess at what a weather map probably looked like on July 4, 1776.

The clear sky and light north wind on the morning of July 4 was indicative of a high-pressure system approaching the area.

In Philadelphia, the wind shifted to the southwest in the afternoon. That means the high-pressure system likely moved off the Eastern Seaboard into the Atlantic, since winds around high-pressure systems flow clockwise.

There could have been another cold front west of the area, but there was no mention of rain by Jefferson until July 8, so perhaps the next front was well out to the west.

While just speculation, here's how the surface weather map could have looked on the afternoon of July 4, 1776.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment