weather.com meteorologists

The rest of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season is expected to be active, and storm numbers have increased in the latest outlook released Wednesday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

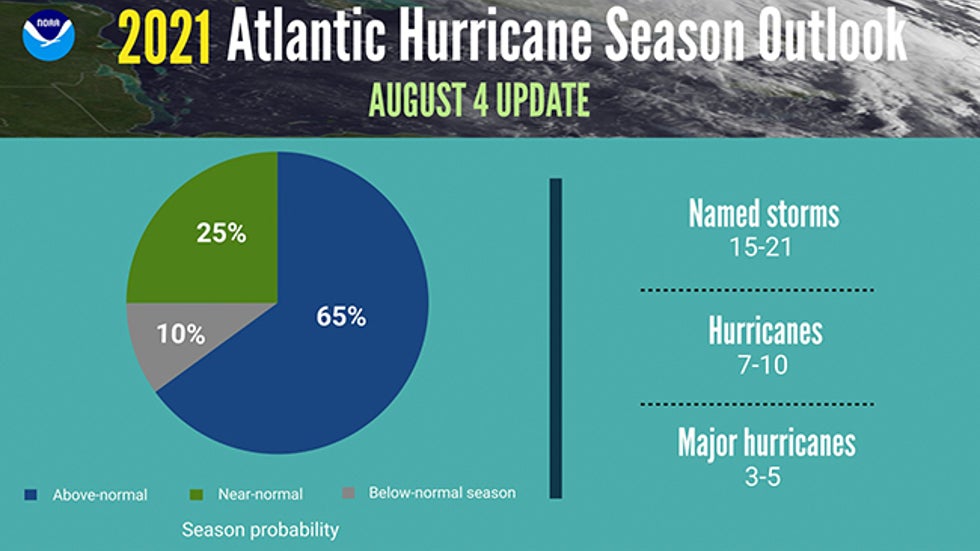

NOAA's early August outlook, the final outlook before the heart of the hurricane season usually kicks into gear, calls for 15 to 21 named storms, seven to 10 of which become hurricanes and three to five of which become Category 3 or stronger.

The outlook includes the five named storms and one hurricane (Elsa) that have already developed. On July 2, Elsa became the earliest fifth named storm on record.

NOAA predicts a 65% chance of a more active than average season, and only a 10% chance of less than average activity in 2021.

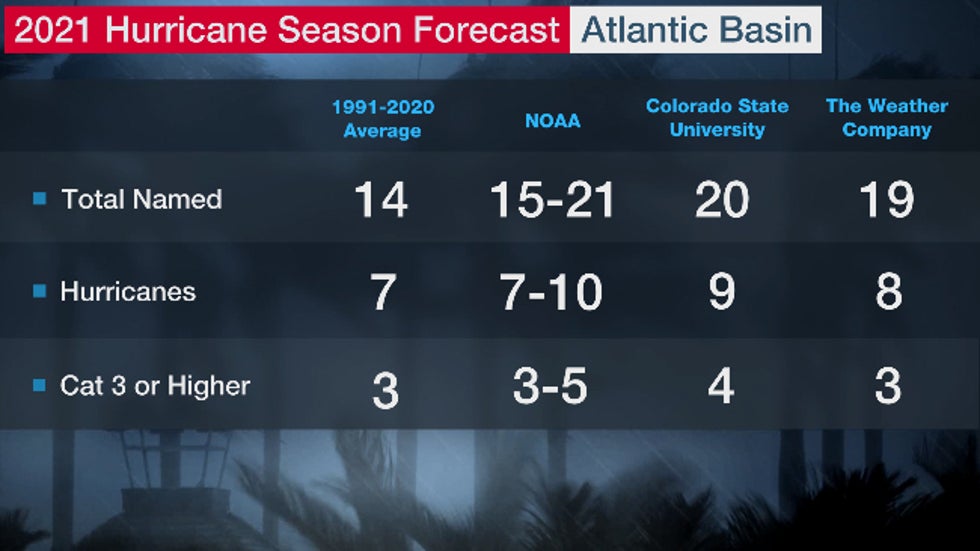

This latest outlook is generally in line with various other outlooks, including those from Colorado State University and The Weather Company, an IBM Business.

These forecasts are above the 30-year average (1991-2020) of 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

(MORE: 2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season Names)

Current 2021 hurricane season outlooks from The Weather Company, Colorado State University and NOAA compared to a 1991-2020 average season.

Current 2021 hurricane season outlooks from The Weather Company, Colorado State University and NOAA compared to a 1991-2020 average season.A record 30 named storms formed in the 2020 hurricane season, 14 of which became hurricanes.

Here are some questions and answers about what these outlooks mean.

What Do Forecasters Examine?

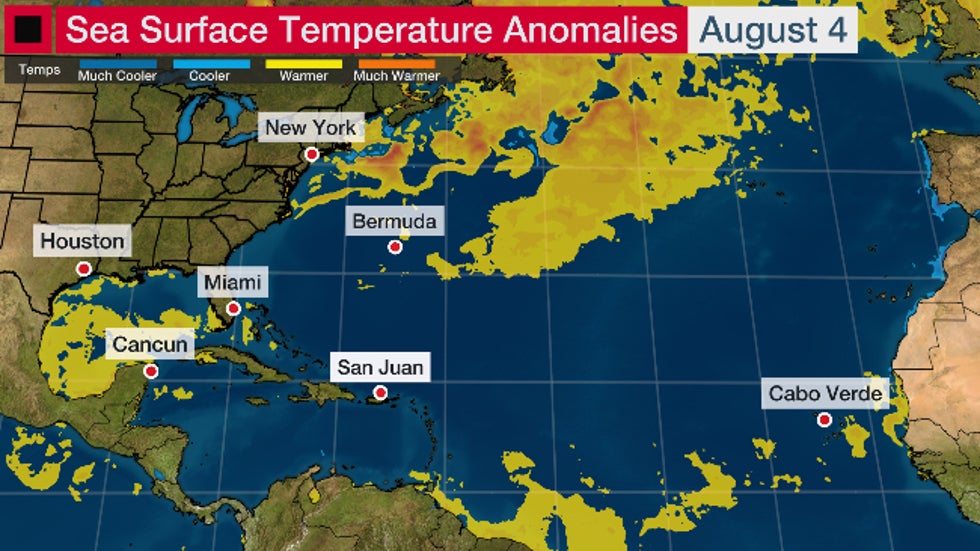

One of the ingredients meteorologists analyze is the water temperature of the Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Basin's waters are warmer than average in the subtropics near and east of Bermuda, off parts of the East Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico.

However, sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic between Africa and the Lesser Antilles have cooled over the last few months and are closer to average or slightly cooler.

The warmth also isn't nearly the magnitude of basinwide warmth seen a year ago, so a repeat of 2020 is not anticipated.

Sea surface temperature anomalies as of Aug. 4, 2021.

Sea surface temperature anomalies as of Aug. 4, 2021.The upper-level pattern this spring in the North Atlantic, with a blocking high pressure near Greenland, helped to increase sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic. However, that upper-level pattern has since changed, which has resulted in a decrease in sea surface temperatures.

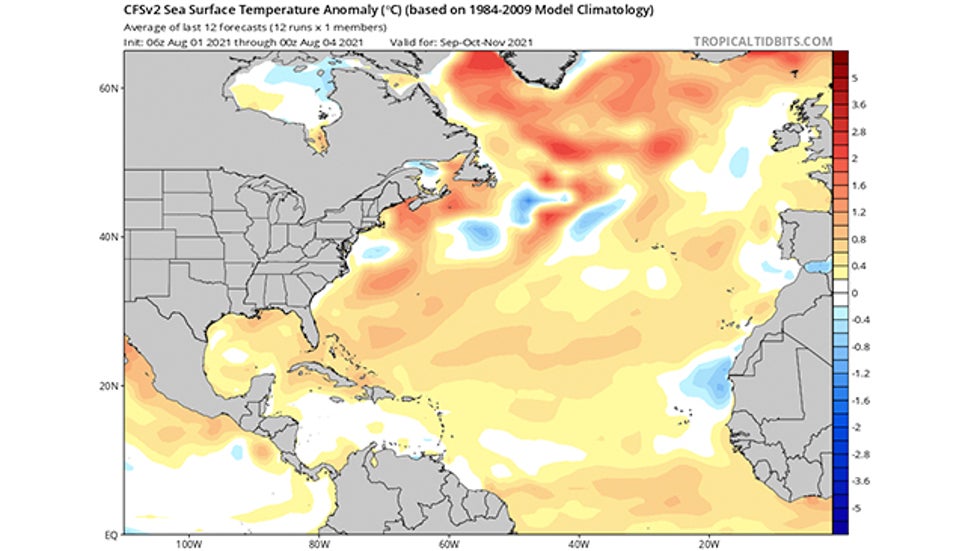

Looking ahead, climate models suggest that most of the basin will be at least somewhat warmer than average from September through November.

Forecast sea-surface temperature anomalies (in degrees Celsius) for September-November 2021 from the CFSv2 model, as of early August 2021.

Forecast sea-surface temperature anomalies (in degrees Celsius) for September-November 2021 from the CFSv2 model, as of early August 2021.An above-average number of tropical storms and hurricanes is more likely if temperatures in the main development region (MDR) between Africa and the Caribbean Sea are warmer than average. Conversely, below-average ocean temperatures can lead to fewer tropical systems.

Assuming atmospheric factors are favorable, warmer waters in the MDR allow tropical waves, the formative engines that can eventually become tropical storms, to get closer to the Caribbean and the U.S.

However, Dr. Todd Crawford, director of meteorology at Atmospheric G2, noted that it is "exceedingly rare to get more than three major hurricanes with sea surface temperatures in the tropics as cool as they are currently."

The prevalence of wind shear and dry air across the Atlantic will also need to be watched over the next few months.

Even if water temperatures are warm and there is little wind shear, dry air can still disrupt developing tropical cyclones and even prohibit their birth.

Hurricanes need a rather precise set of ingredients to come together in order to fester, so all of these ingredients will need to be monitored this year.

How Much of a Role Will La Niña Play?

El Niño/La Niña, the periodic warming/cooling of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific Ocean, can shift weather patterns and influence winds in the Atlantic Basin during hurricane season.

La Niña ended early this year and ENSO-neutral conditions (neither El Niño nor La Niña) are present.

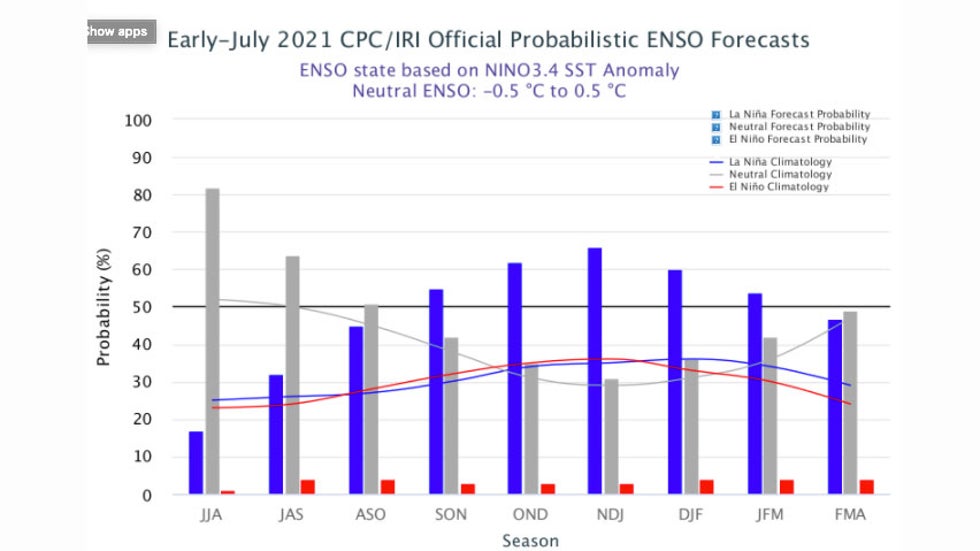

However, NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña watch in its early July update. There are indications that La Niña may emerge again during the September through November period and last through the upcoming winter.

Early July 2021 model-based forecast probabilities for La Niña (blue bars), neutral (gray bars) and El Niño (red bars) into early 2022.

Early July 2021 model-based forecast probabilities for La Niña (blue bars), neutral (gray bars) and El Niño (red bars) into early 2022.La Niñas typically correspond to more active hurricane seasons because the cooler Eastern Pacific water produces weaker trade winds and less wind shear in the Caribbean Sea that would otherwise rip apart hurricanes and tropical systems trying to develop.

Such was the case in 2020 when La Niña intensified to become the strongest in 10 years. This was one factor behind a record 30 named storms in 2020.

But while La Niña has fizzled for now, its influence on the atmosphere is likely to remain in place the remainder of hurricane season.

What Does This Mean for the U.S.?

A record 11 storms made landfall in the U.S. in 2020, including six hurricanes: Hanna, Isaias, Laura, Sally, Delta and Zeta.

(MORE: Laura, Entire Greek Alphabet Retired Following 2020 Hurricane Season)

That's well above the average of one to two hurricane landfalls each season, according to NOAA's Hurricane Research Division.

Despite the record 2020 season, there isn't necessarily a strong correlation between the number of storms or hurricanes and U.S. landfalls in any given season. One or more of the named storms predicted to develop this season could hit the U.S., or none at all.

Some past hurricane seasons have been inactive but included at least one notable landfall.

The 1992 season produced only six named storms and one subtropical storm. However, one of those named storms was Hurricane Andrew, which devastated South Florida as a Category 5 hurricane.

In 1983, there were only four named storms, but one of them was Alicia. The Category 3 hurricane hit the Houston-Galveston area and caused almost as many direct fatalities there (21) as Andrew did in South Florida (26).

On the other hand, the 2010 Atlantic season was very active, with 19 named storms and 12 hurricanes. Despite the high number of storms that year, no hurricanes and only one tropical storm made landfall in the U.S.

In other words, a season can deliver many storms but have little impact, or deliver few storms and have one or more hitting the U.S. coast with major impact.

It's impossible to know for certain if a U.S. hurricane strike will occur this season. A weak tropical storm hitting the U.S. can cause major impacts, particularly if it moves slowly and its rainfall triggers flooding.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment