Jonathan Belles

With hurricane season getting underway, if you're a resident of a coastline or just interested in hurricanes, we are sure you have questions.

Because it's always better to be prepared than scared when a hurricane approaches, here are 10 of the most frequently asked questions we receive during hurricane season.

1. When is hurricane season and when do I need to worry?

Hurricane season in the Atlantic, Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico runs from June 1 to Nov. 30. Storms like Hurricane Alex, a rare January hurricane in 2016, and recent tropical storm Ana have shown us that the ocean doesn’t always play by a strict set of rules. Storms can occur at any time of the year but are most likely to occur during the summer and autumn months due to the warmer waters.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June to November and peaks in activity in early September.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June to November and peaks in activity in early September.We should always be in a state of preparedness for weather. Worrying can make us less prepared for tropical systems because we can forget things or make knee-jerk decisions when stressed. Worrying lowers the amount of information that can be obtained from forecasters and lessens our decision-making capabilities, according to COMET/MetEd's Best Practices in Tropical Cyclone Briefings.

2. When are advisories issued?

The National Hurricane Center issues statements on active tropical cyclones at least four times a day for tropical systems and disturbances in both the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific basins. Advisories are issued at 5 a.m., 11 a.m., 5 p.m. and 11 p.m. EDT.

For more urgent cases, like a landfalling tropical storm or hurricane, the NHC produces intermediate advisories an additional four times a day. Intermediate advisories are issued when tropical storm or hurricane watches and warnings are issued.

When a hurricane, tropical storm or depression is active, the NHC produces a suite of products that include information about the future track, intensity and potential impacts that a storm may bring to a certain location.

3. I’m outside of hurricane X’s forecast cone. I’m safe, right?

The cone of uncertainty, in blue, underlaid by the chances that winds of greater than 39 mph will impact a given area, with increasing chances as the colors turn from green to orange.

The cone of uncertainty, in blue, underlaid by the chances that winds of greater than 39 mph will impact a given area, with increasing chances as the colors turn from green to orange.No. The forecast cone for hurricanes, tropical storms and tropical depressions is based on the track error of past forecasts in the last five years.

The cone contains no information about how the given tropical system will impact you, or about a forecaster’s confidence level. The cone contains 67% of the errors made in forecasts in the last five years.

Generally, if a certain season was harder to forecast, the cone will get bigger the next year due to the higher amount of errors made. The opposite is true, too – if a hurricane season had easier forecasts, the cone will get smaller. Over the last few decades, the forecast cone has gotten slightly smaller.

The cone contains no information about impacts, and this makes sense if you think about it. If the storm is directly on top of you, the cone is ahead of the likeliest forward movement of the storm. A few hours after it moves by, you’re still likely to see rain, wind and otherwise unpleasant weather. You are no longer in the cone. The same can be said ahead of a tropical system on either side of the forecast cone. You likely won’t get the center of the system, but you will get impacts.

It is also important to note that you should not focus on the center of the forecast cone. Although that would typically be the safest bet for where the center of a storm will go, small wobbles can drastically change the long-term forecast.

4. What do different categories mean and what are the criteria?

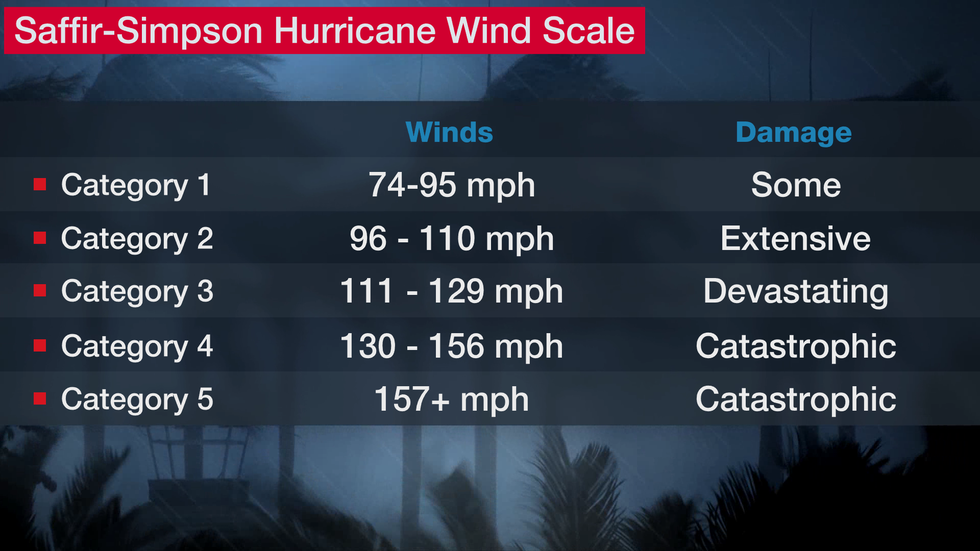

The scale used by the NHC is called the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

This scale is broken down into five categories of maximum sustained wind strength ranging from 74 mph to 157 mph and above. Winds can often gust considerably higher than sustained winds, especially between large structures, like skyscrapers and underpasses, and at higher elevations. The higher the category, the more destructive the hurricane generally is. A Category 1 hurricane can bring some damage, but a Category 5 hurricane can bring about catastrophic damage.

The scale has undergone updates in recent years based on scientific and communication tweaks, and also to remove storm surge from the scale. Storm surge can vary drastically within a single category.

5. What is storm surge, and why is it so deadly?

Large and/or strong hurricanes and tropical storms often collect and push water ahead of them. This collects and forms into a "hill of water" generally to the right side of a hurricane and ahead of the center. That hill becomes destructive when it approaches the shallow waters near a landmass. If winds are strong enough or have enough momentum, that water is forced to inundate coastal areas.

Storm surge is the reason why the vast majority of coastal cities have set up evacuation zones. These zones are based on past hurricanes and ocean models used by meteorologists.

Storm surge can damage structures along the coast, including homes, bridges, roads and sometimes even entire communities. According to stormsurge.noaa.gov, 72% of ports, 27% of major roads and 9% of rail lines within the Gulf Coast region are at or below 4 feet in elevation, making these economic points of interest more vulnerable to storm-surge damage.

Storm surge is dangerous enough that the NHC will offer watches and warnings this year for the potential and likelihood, respectively, for coastal inundation. The NHC will also offer a reasonable worst-case coastal flooding scenario for landfalling storms.

6. What's the difference between tropical storm and hurricane watches and warnings?

An example of a tropical watch and warning map.

An example of a tropical watch and warning map.When winds of 39 mph or higher associated with a tropical system are forecast to threaten land in 48 hours and winds of 74 mph or higher are possible, the NHC will give residents in the threatened area a heads up to “watch” the system and begin making final preparations.

When winds of 39 mph or higher associated with a hurricane are likely to impact a landmass in 36 hours and winds of 74 mph or higher are likely, the NHC will give residents in the threatened area a “warning” to finalize preparations. Outdoor activities will become difficult in 36 hours or fewer.

When winds of 39 mph or higher associated with a tropical storm are forecast to threaten a landmass in 48 hours, the NHC will give residents in the threatened area a heads up to “watch” the system and begin making preparations, if they aren't already underway.

When winds of 39 mph or higher associated with a tropical storm are likely to impact a landmass in 36 hours, the NHC will give residents in the threatened area a “warning” to finalize preparations. Outdoor activities may become difficult in 36 hours or fewer.

Hurricane warnings may be kept in place after winds decrease if dangerous storm surge or waves are expected to continue.

7. What's the difference between a hurricane and a typhoon?

Cyclone names around the world.

Cyclone names around the world.Meteorologically, cyclones are the same around the globe with one exception: south of the equator, hurricanes spin clockwise instead of counterclockwise, like they do in the Northern Hemisphere.

Depending on the ocean basin, hurricanes are also named differently. For instance, in the Western Pacific, hurricanes are called “typhoons.” In the Indian Ocean, they are called some variant of "cyclones."

8. What in the world is a(n) _________?

- Cyclone: A generic name for a low-pressure system or, specifically, a tropical low-pressure system in the Indian Ocean with winds higher than 74 mph.

- Subtropical [storm, depression, low, cyclone]: A low-pressure system with characteristics common in both tropical and northern-latitude systems, with a name matching the varying intensity of the system. Like tropical systems, they usually form over warm waters, have frequent persistent thunderstorms and must have a closed circulation. Unlike a tropical system, these systems are often linked to the jet stream or a cutoff low-pressure system. They derive their energy from a combination of warm waters and upper-level support.

- Invest: A weather system that the NHC is interested in learning more about or is interested in exercising its model guidance and other technology on. Designation of a weather system does not make any suggestions about system strength or future development.

- Post-tropical [storm, depression, cyclone]: A former storm that no longer has characteristics of a tropical system. These systems can and often do contain hazards (heavy rain, gusty winds, beach erosion) similar to their tropical predecessors.

- Potential Tropical Cyclone: A tropical disturbance that is already producing, or is likely to produce, winds over 39 mph but does not yet have a closed center of circulation. Tropical storm watches or warnings are issued for these systems.

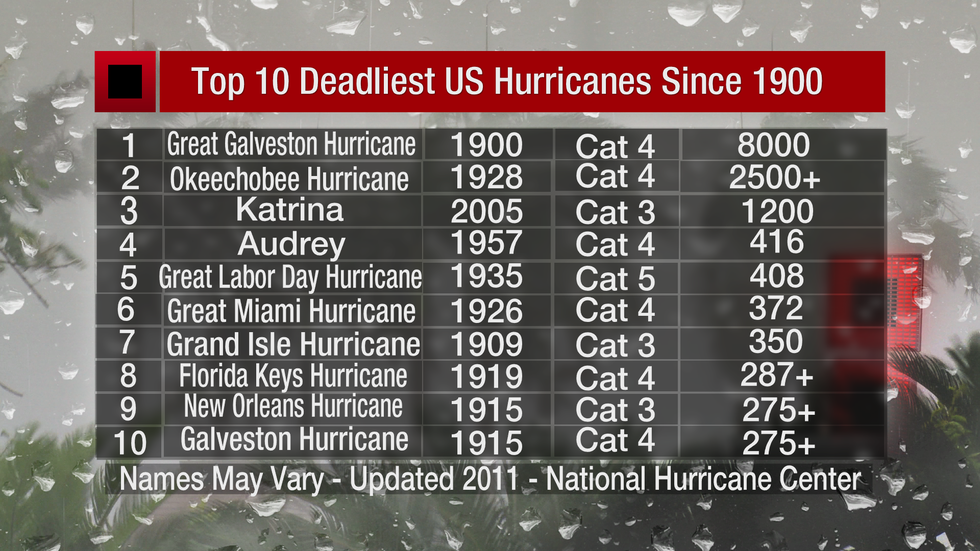

9. What were the deadliest Atlantic hurricanes in the United States?

Deadliest hurricanes to strike the mainland United States.

Deadliest hurricanes to strike the mainland United States.In the Atlantic Basin, one in every five or six tropical cyclones causes loss of life (Rappaport 2014), and hurricanes remain a large threat to the U.S.. An average of 50 deaths occurred yearly, directly and indirectly, due to tropical cyclones between 1963 and 2012.

If U.S. territories were included on this list, Hurricane Maria would have made it to No. 2 on the list. Maria killed at least 2,981 people in Puerto Rico in 2017.

Hurricane deaths have generally decreased since 1900 due to more advanced warnings, better preparedness campaigns and better communication.

This is not to say that hurricanes or even tropical storms are less impactful, but public awareness is increasing. Of course, you can always find the latest here on weather.com.

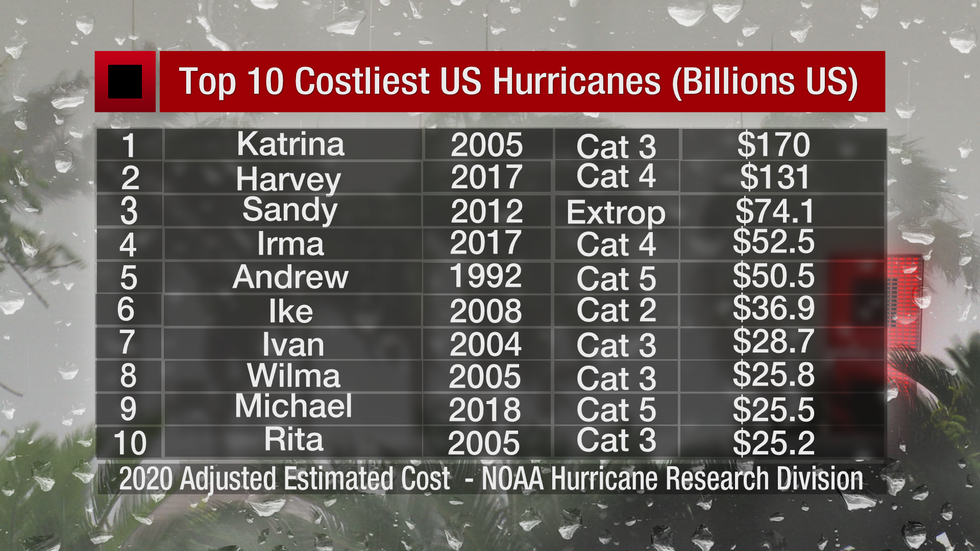

10. What were the costliest Atlantic hurricanes in the United States?

Costliest hurricanes to strike the mainland United States.

Costliest hurricanes to strike the mainland United States.Hurricanes continue to be a large portion of billion-dollar disasters in America. It is important to note that the category of the hurricane does not cleanly relate to how much a storm will damage.

In fact, according to NOAA's Hurricane Research Division, Allison comes in at No. 17 on this list as a tropical storm with Sandy included in the rankings. Allison caused $12.6 billion in damage.

Factors that could change how much damage a hurricane or tropical storm causes include the density of the area the hurricane hits, the strength of the tropical cyclone, the forward speed at which the system is moving and the size of the system.

The combination of a large, slow-moving, Category 5 hitting a very densely populated area would really rack up damage costs.

Vulnerability also increases costs, especially after extended hurricane droughts. Tampa Bay, New Orleans, the Chesapeake Bay area and New York would be more likely to have damage due to either the shape of their coastlines, hurricane amnesia or a combination of the two.

If U.S. territories were included on this list, Hurricane Maria would have made it to No. 3 on the list. Maria caused $94.5 billion in damage in Puerto Rico in 2017.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment