Jonathan Erdman

The risk of spring flooding in 2021 is higher in parts of the Midwest, but lower than average in the Plains and West due to a combination of factors already in place and those that could develop through May.

Spring flooding is an annual concern not only in areas blanketed by snow that has to melt, but also areas farther downstream where the volume of water from melted snow and rainfall eventually drains.

Spring flooding has exacted a costly toll in the U.S., particularly in recent years.

In 2019, a March bomb cyclone unleashed record flooding in Nebraska and neighboring states that lasted for months. Flooding along stretches of the Mississippi River lasted into the summer and historic Arkansas River flooding beginning in late May swamped parts of Oklahoma and Arkansas.

The combined damage from these three flood events was just over $20 billion, according to NOAA.

Photos of Spencer Dam, along the Nebraska-South Dakota border, before and after the dam was destroyed by flooding in March 2019.

Photos of Spencer Dam, along the Nebraska-South Dakota border, before and after the dam was destroyed by flooding in March 2019.Spring Flood Outlook

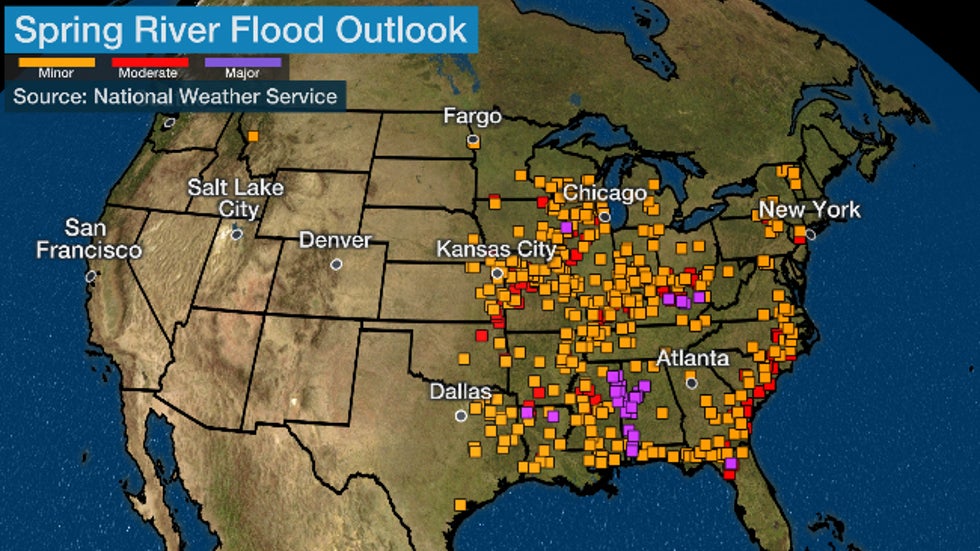

Here is our outlook for spring flooding by region, relative to a typical spring.

-Northeast: Near or below-average risk

-Ohio Valley, mid-Mississippi Valley, lower Mississippi Valley: Above-average risk

-Southeast: Near or above-average risk

-Plains and much of the West: Below-average risk

-Northwest: Near or below-average risk

This map indicates locations with a greater than 50% chance of exceeding flood stage from March through May 2021, as of March 3. Potential peak spring flood stages are color-coded by severity.

This map indicates locations with a greater than 50% chance of exceeding flood stage from March through May 2021, as of March 3. Potential peak spring flood stages are color-coded by severity.Now, let's break down the flood factors meteorologists examine.

Where Rivers are Already Running High

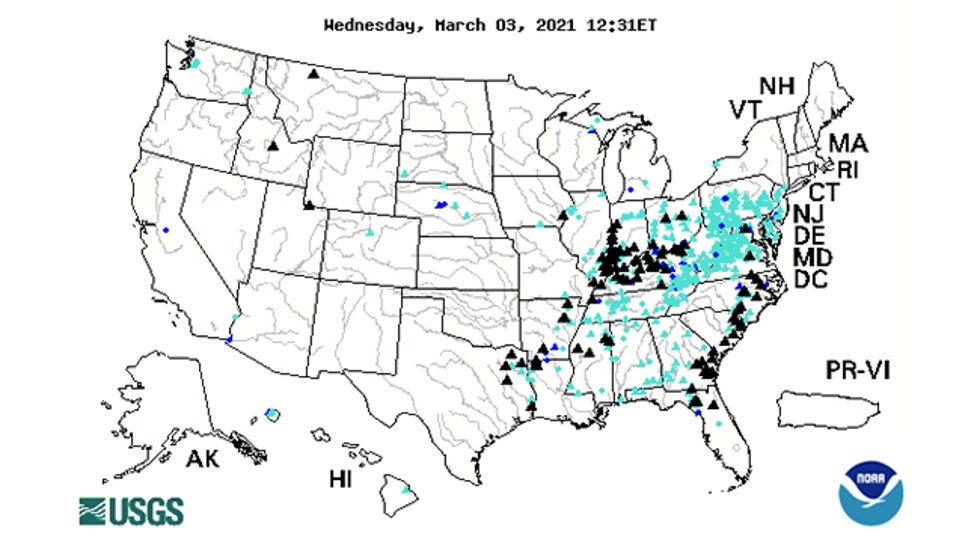

As of early March, a number of rivers were above flood stage, primarily in the Ohio Valley, parts of the lower Mississippi Valley and along the Southeast coastal plain from Virginia to northern Florida.

Heavy rain during the last weekend of February triggered much of the flooding in the Ohio Valley.

But there are a number of other rivers in the East that were running in their highest percentiles (95th and above) for early March, shown by the teal markers in the map below.

Rivers in these watersheds can't absorb any additional water at the moment.

Conversely, note the dearth of river gauges reporting high levels in the western half of the country.

Gauges that recorded river levels in the top 5 percent (teal) and top 1 percent (blue) in their historical record for March 3 are shown by teal and blue markers, respectively. Those gauges that reported levels above flood stage on March 3, 2021, are shown by the black markers.

Gauges that recorded river levels in the top 5 percent (teal) and top 1 percent (blue) in their historical record for March 3 are shown by teal and blue markers, respectively. Those gauges that reported levels above flood stage on March 3, 2021, are shown by the black markers.Soaked Soil?

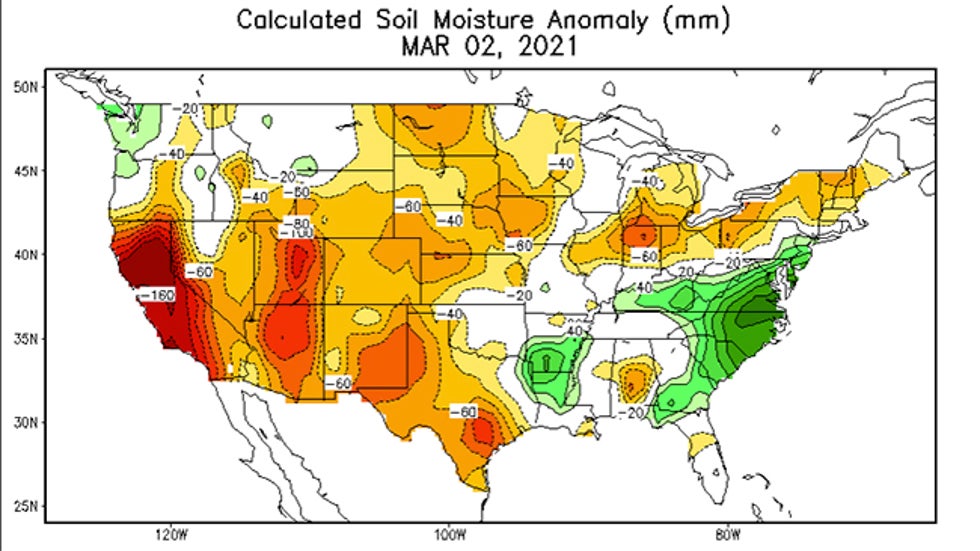

The next thing meteorologists examine to determine flood risk is soil moisture.

In this case, there's a lot of good news. Much of the Lower 48 states have drier than average soil conditions by early March standards.

Anomalies of soil moisture (in millimeters) on March 2, 2021. Wet (dry) soil moisture anomalies are indicated by progressively darker green (red) contours in the map.

Anomalies of soil moisture (in millimeters) on March 2, 2021. Wet (dry) soil moisture anomalies are indicated by progressively darker green (red) contours in the map.However, most of those anomalies in the Plains and West are due to the ongoing, expansive drought, which is raising concerns for wildfires, in addition to potential impacts on agriculture and water supply if the drought persists or worsens.

But in parts of the Midwest and Northeast, soil moisture is also lagging.

Dry soil absorbs water from precipitation or melting snow more effectively. Saturated ground can't do that, instead forcing water to run off directly into creeks, streams, rivers and lakes.

There's another factor in the ground that may also contribute to a lower flood threat.

"The fact that we have very little or very shallow ground frost should allow more of that melt water to soak into the soil than we usually have," said Michael Welvaert, senior hydrologist with the National Weather Service's North Central River Forecast Center, in an email to weather.com.

Despite a cold February, particularly in the Plains, a milder December and January hasn't allowed a deep freeze of the soil in the northern U.S. that could repel water much like soaked or saturated soil would.

However, parts of Arkansas and Louisiana, and especially from southern New Jersey to Kentucky to the Carolinas and south Georgia have much soggier soil than typical in early March.

Snowpack

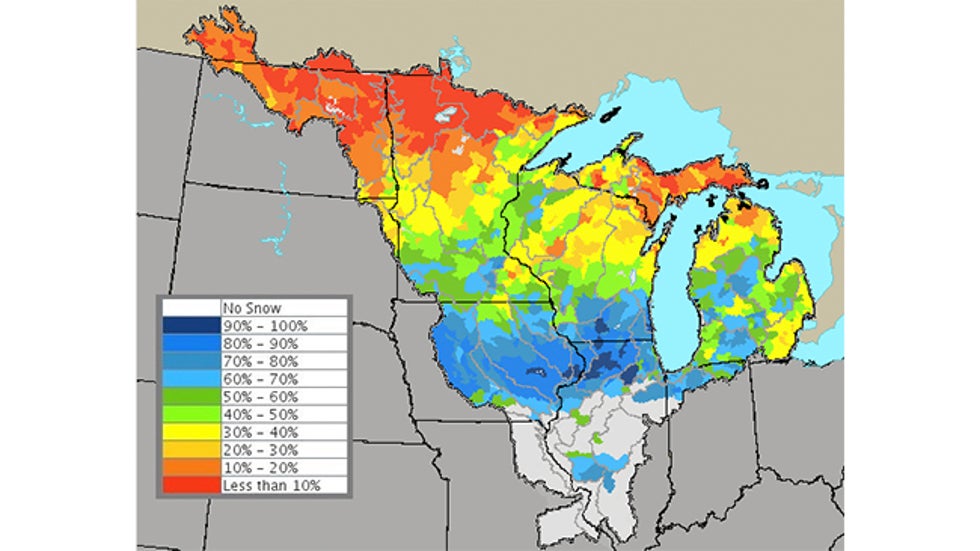

For flood forecasting, the pertinent question to ask is not necessarily how much snow there is left to melt, but how much water is locked up in the snowpack.

In this regard, there is generally more good news.

Since the record-smashing cold outbreak and siege of winter storms in February, temperatures have warmed in the central and eastern U.S., but not rapidly.

This has lead to a slow, steady snowmelt in much of the Plains, Midwest and Northeast.

"So far, our melt has been pretty ideal," said Welvaert, referring to the upper Midwest retreat of snow cover.

"Warm temperatures in the daytime get the melt going, then temperatures fall to freezing or below overnight to stop new melt, and allow the previous day's melt water to run out of the system before adding more."

Another good sign early in spring is lower than average snow cover in the northern Great Lakes and Red River Valley.

The water content of the snowpack in parts of North Dakota, northern Minnesota and Michigan's Upper Peninsula was in the lowest 10% on record for early March, according to an analysis by the NWS-North Central River Forecast Center.

Percentiles of the water content of the snowpack on March 1, 2021. A 90-100% value (darkest blue) corresponds to snow water content in the top 10% of the historical record for the date.

Percentiles of the water content of the snowpack on March 1, 2021. A 90-100% value (darkest blue) corresponds to snow water content in the top 10% of the historical record for the date.There are some areas of concern, though.

In that same NWS analysis above, the snowpack's water content in parts of Iowa, southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois was in the top 10% of historical values for early March.

There's also some impressive snowpack in parts of the Northeast.

"We currently have 3 to 5 inches of water stored in the snowpack in the Poconos (Pennsylvania) and Catskills (New York) where snow has been above average for the season," said Robert Shedd, hydrologist at the NWS Middle Atlantic River Forecast Center in an email to weather.com.

"This is more than we have had in early March for the past several years."

However, Shedd said generally drier weather in the near-term with some brief warm-ups should allow for a slow snowmelt with a low flood risk in those areas.

In the West, the water content of the snowpack is generally near average in much of the Rockies, except for Utah and New Mexico, and below average in California's Sierra Nevada.

Only the Washington Cascades were above average, but not extremely so.

Spring's Wildcards

We've just discussed conditions in place as of early March, without yet taking into account how wet this spring could be.

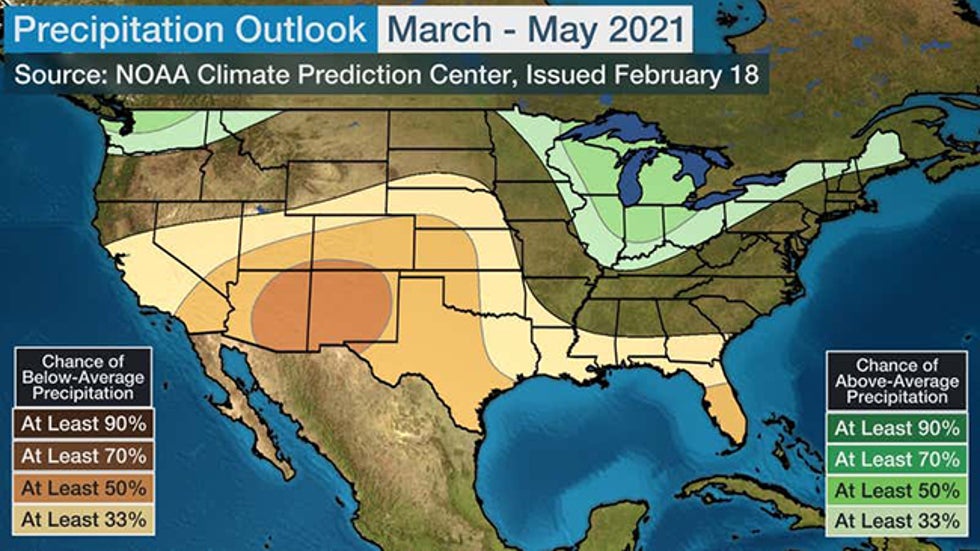

According to the latest outlook available at the time this article was published from NOAA's Climate Prediction Center, parts of the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, interior Northeast and Northwest had the best chance of a wetter spring.

Much of the Southwest, central and southern Plains and Florida had the best chance of a drier spring.

The March-May 2021 precipitation outlook shows increasing chances of above-average (in progressively darker green contours) and below-average (in progressively darker brown contours) precipitation. Uncontoured areas have an equal chance of a wet or dry spring.

The March-May 2021 precipitation outlook shows increasing chances of above-average (in progressively darker green contours) and below-average (in progressively darker brown contours) precipitation. Uncontoured areas have an equal chance of a wet or dry spring.While far from the only factor, one influence on this spring pattern is a moderate-strength La Niña. The opposite of El Niño, this is the periodic cooling of the equatorial Pacific Ocean that typically exerts some influence on weather patterns, particularly in winter and spring.

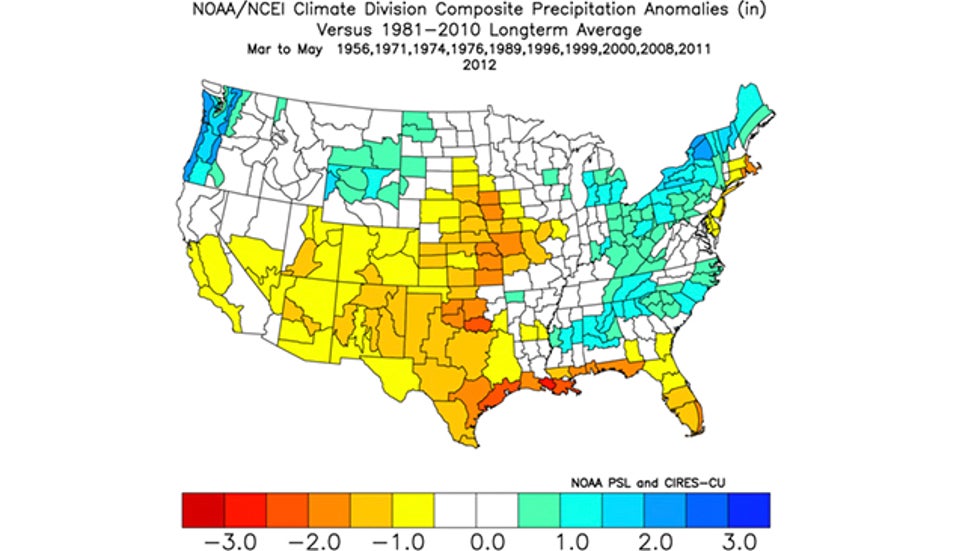

Looking at 11 previous moderate or strong La Niña springs since 1956, you'll notice a general pattern of a wetter East, Great Lakes, Ohio Valley and Northwest, but a drier Plains, Southwest and Gulf Coast into Florida as the map below shows.

Composite March - May precipitation anomalies (in inches) during 11 moderate or strong La Niñas since 1950. Wetter anomalies are in teal and blue contours. Drier anomalies are in the yellow and orange contours.

Composite March - May precipitation anomalies (in inches) during 11 moderate or strong La Niñas since 1950. Wetter anomalies are in teal and blue contours. Drier anomalies are in the yellow and orange contours.But there are several spring wildcards that can heavily influence the severity of spring flooding that are difficult to pinpoint in a long-range outlook.

Spring snowstorms can dump heavy, wet snow in parts of the West, Plains, Midwest and Northeast into April, sometimes even early May, adding to the snow that has to melt later.

A sharp warm-up with plenty of sunshine and temperatures remaining above freezing at night can melt snow rapidly, sending water quickly into streams, creeks, rivers and lakes. The warmer the spell, the faster the melt.

Ice jams are another problem each spring, which can cause unexpected sharp rises on thawing rivers.

Finally, heavy rain is a frequent problem in the spring.

Last May, a gyre of low pressure triggered major flash flooding in Chicago, overwhelmed a pair of Michigan dams, and triggered flooding in parts of Kentucky, Ohio, Wisconsin, the Carolinas and Virginia.

Heavy rain over saturated ground after snow has just melted, or over a basin with rivers still swollen from snowmelt are just a couple flood scenarios.

If that heavy rain falls on existing snowpack, water locked in the snow can be released together with the rainfall, leading to a particularly serious flood threat.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment