Tom Niziol

Nature moves on all different time scales. A tornado or flash flood is a weather extreme that can happen in almost an instant, catching unsuspecting victims off guard.

Some weather phenomena occur on a much slower time scale but nonetheless can produce significant property damage to unsuspecting homeowners.

Ice shoves are a great example of this “slow-motion” weather phenomenon.

An ice shove is a surge of ice that piles up on the shore of a body of water, typically an inland lake.

The movement of the ice is modulated by strong winds and currents as well as temperature changes.

Although ice shoves can occur any time there is ice cover on a body of water, conditions tend to be most favorable during the “ice breakup” time frame that typically extends from late winter through mid-spring.

In spring, the large mass of ice covering a body of water is subject to melting and begins to move and break up under the influence of winds. Sustained periods of strong winds along the longer axis - or fetch - of the lake can begin to slowly move the ice sheet toward the downwind shore.

Comparison of ice cover on March 19 and 20, 2021, on Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin. Winds out of the northeast on March 18 pushed the ice pack toward the southern two-thirds of the lake. However, two days of warm southerly winds from March 19-20 broke the ice pack up and pushed it back against the northern shore of the lake around Appleton, Wisconsin.

Comparison of ice cover on March 19 and 20, 2021, on Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin. Winds out of the northeast on March 18 pushed the ice pack toward the southern two-thirds of the lake. However, two days of warm southerly winds from March 19-20 broke the ice pack up and pushed it back against the northern shore of the lake around Appleton, Wisconsin.Once that huge wind-driven mass of ice, sometimes covering 100 square miles or more on larger bodies of water, gets moving, there is a tremendous amount of momentum and force behind it.

I like to equate the momentum of the ice as a train with hundreds of loaded cars behind it. All of that momentum takes a tremendous amount of power to slow and bring to a stop. In the case of the ice sheet, which equates to thousands of railroad cars, the shoreline is the stopping point.

However, as long as the ice sheet has fuel in the form of wind to move it along, nothing will stop it in its path, like one train car after another plowing one on top of the other into the shore.

It’s been referred to as a kind of slow-motion version of a frozen tsunami as the leading edge of the ice sheet begins to pile up on shore. It can also be compared to the slow movement of a glacier, except the glacier moves by gravity, whereas the ice shove is moved by the wind and water currents.

Above: An example of an ice shove along the Lake Superior shoreline in Ashland, Wisconsin, in March 2021. (Credit: Cheryl Koval)

As long as winds remain relatively strong - say, 25 mph or more - for an extended period of time, the sheet of ice will continue to push against the downwind shoreline with chunks piling up to 30 to 40 feet at times.

For homeowners of lakeshore property, the impacts can be devastating, sometimes in a surreal way.

That’s because the damage occurs at a very slow pace. The homeowners watch as the ice slowly encroaches on the land and drives forward toward structures with no way to stop it. The sheer force of that much weight will take out just about anything in its path, as the first video atop the article illustrates.

Ice shoves can occur anywhere around the world where ice cover develops on bodies of water and conditions are favorable to move the ice sheet.

Across North America, lakes from Utah through Missouri to the upper Midwest and the Great Lakes region to Long Island are known to have experienced ice shoves.

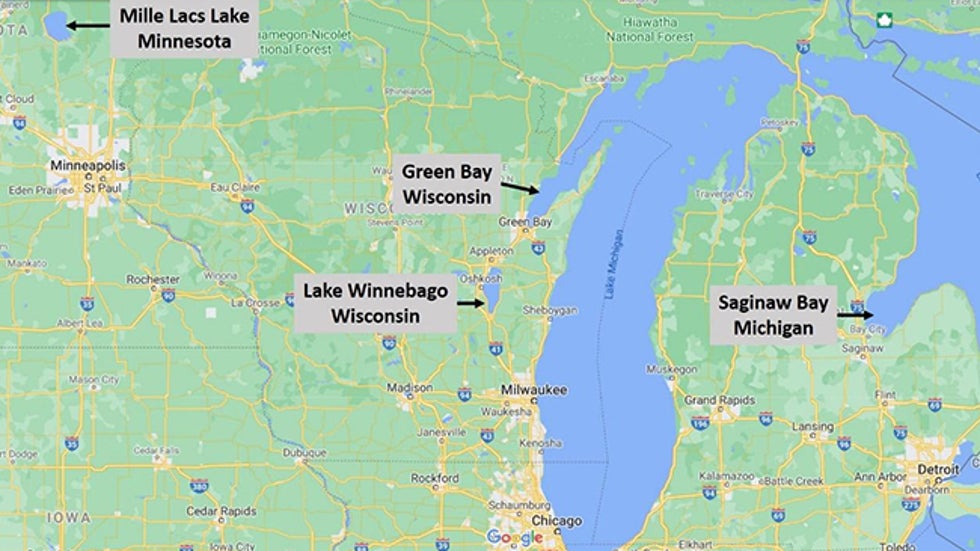

Some of the most common areas to experience them include Mille Lacs Lake in Minnesota, about 100 miles north of Minneapolis, and Lake Winnebago in Wisconsin. Some of the larger bays on the Great lakes are also favorable locations for ice shoves each spring season, including Green Bay and Saginaw Bay.

On March 11, an extended period of southwest winds on Saginaw Bay pushed a large ice sheet toward the eastern shore.

The satellite animation below shows the movement of the ice pack from 1-7 p.m. You can see how southwest winds gusting as high as 55 mph were able to move the entire ice pack - about 300 square miles - toward the eastern shore of the lake.

Satellite animation of the ice pack on Saginaw Bay, Michigan, from 1-7 p.m. on March 11, 2021. Southwest winds gusting as high as 55 mph were able to push the entire ice pack toward the eastern shore of the bay.

Satellite animation of the ice pack on Saginaw Bay, Michigan, from 1-7 p.m. on March 11, 2021. Southwest winds gusting as high as 55 mph were able to push the entire ice pack toward the eastern shore of the bay.The video in the tweet below shows the power of nature as that ice piled up along the shoreline.

Ice shoves can occur on really big lakes, too.

In 2019, strong southwest winds blowing along the 225-mile length of Lake Erie pushed tons of ice onshore at Port Colborne, Ontario.

The images of that ice shove were amazing as huge chunks of ice breached the break wall along the shore.

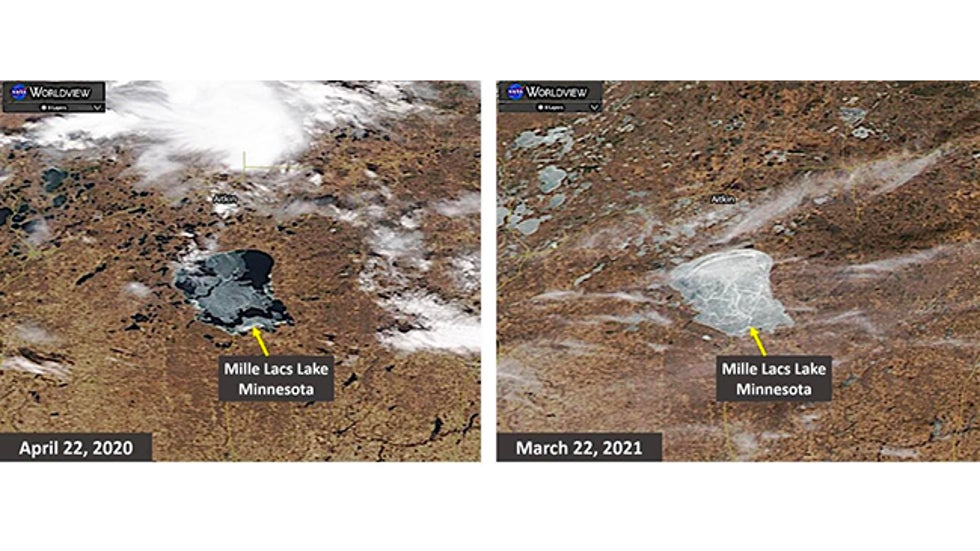

There are still many lakes that have significant ice cover across the Upper Midwest, including one of the most notorious locations at Mille Lacs Lake in Minnesota.

Comparison of Mille Lacs Lake, Minnesota, ice cover on April 22, 2020 (left) during a major ice shove and March 22, 2021 (right).

Comparison of Mille Lacs Lake, Minnesota, ice cover on April 22, 2020 (left) during a major ice shove and March 22, 2021 (right).I have a feeling we haven’t seen the last of this truly surreal weather phenomena. Stay tuned for more!

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment