Jonathan Erdman

Three interesting features in the weather pattern, including a weaker polar vortex, could combine to make the rest of January and February more active for winter storms and cold in the eastern United States.

Interestingly, one of those features is not La Niña, the periodic cooling of water near the equator in the eastern Pacific Ocean, which intensified in the fall and can have impacts on winter weather in the U.S., including snowier winters for some.

The borderline strong La Niña is still there, but its influence on the atmosphere may be overridden by a trio of weather patterns that could have important consequences on the rest of winter's weather.

1. The Greenland Block

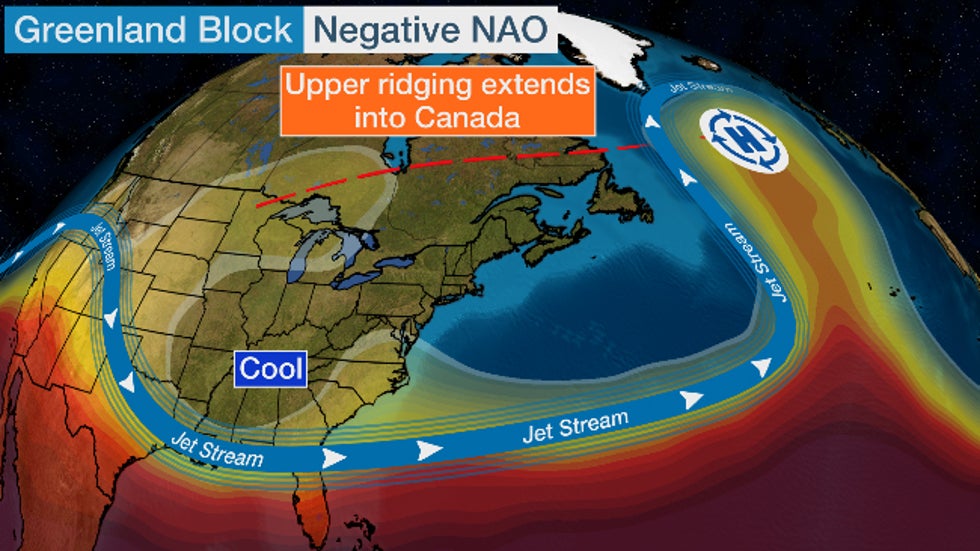

The Greenland block is a relatively warm bubble of high pressure about 17,000 to 20,000 feet above the ground that can set up, as its name suggests, near Greenland.

Meteorologists monitor the strength, or lack of, a Greenland block by examining an index called the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), which can oscillate over the course of days or weeks. When this index is more strongly negative, blocking high pressure near Greenland is stronger.

When this negative NAO pattern sets up, winter weather fans in the eastern U.S. salivate.

SPONSORED: Bundle up this winter with a gravity blanket

That's because this nose of high pressure aloft acts like a rock in a stream, forcing the polar jet stream to plunge southward across the central and eastern U.S., pulling cold air from Canada.

Nosediving jet streams can spawn strong storms with heavy snow. The Greenland block can force these storms to crawl slowly up the East Coast rather than simply sweeping quickly from west to east across the U.S. or Canada and out to sea.

This Greenland block is currently quite strong and expected to linger a while. More about that a bit later.

The upper-level pattern as of the week of Jan. 4-8, 2021, includes a prominent Greenland block, with some upper-ridging extending west into Canada.

The upper-level pattern as of the week of Jan. 4-8, 2021, includes a prominent Greenland block, with some upper-ridging extending west into Canada.However, there's a monkey wrench in this pattern.

In a YouTube video recorded earlier this week, Michael Ventrice, a meteorological scientist at The Weather Company, an IBM Business, pointed out warm air aloft, and at the surface, extends westward into much of Canada and the northern tier of the U.S.

So although this negative NAO pattern is bringing some colder air into the South, it's not very cold by January standards.

High temperatures near the U.S.-Canadian border are topping out in the 20s or 30s, well above average nearing what is typically the coldest time of year.

But that might change later this month.

Longer-range models suggest this Canada ridging could retreat northward closer to – you guessed it – Greenland during the last half of January, according to Ventrice.

This could open the door to more of the East Coast and Midwest for more winter storms from late January into at least early February.

2. The Pacific-West Coast Ridge

In recent weeks, the Pacific jet stream has delivered a series of wet, windy storms to the Pacific Northwest and Northern California, and delivered relatively mild, Pacific air to much of the rest of the country.

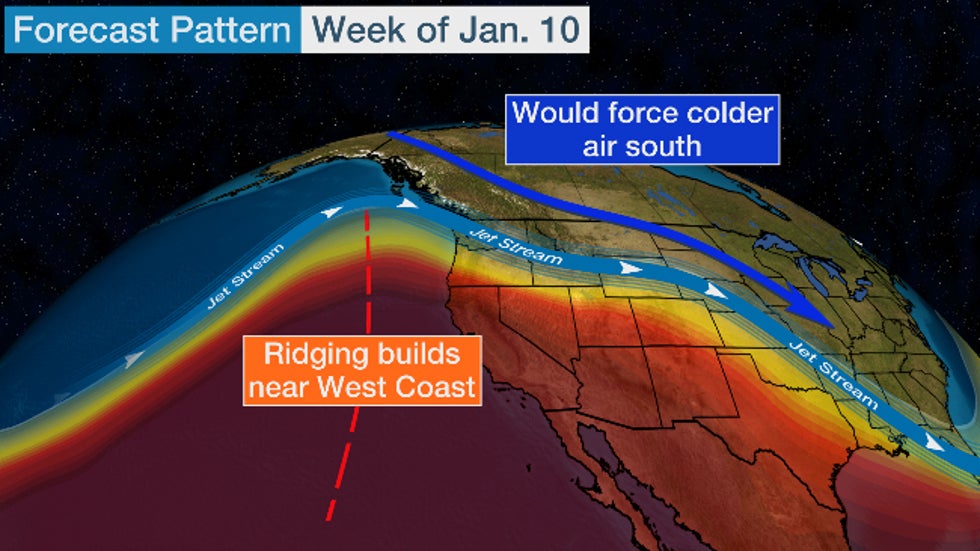

That pattern is expected to change next week.

Instead of the Pacific jet plowing into the West Coast, high pressure aloft, similar to the Greenland block, is expected to strengthen near the West Coast and nose its way northward toward Alaska.

This pattern fluctuation is known to meteorologists as the negative phase of the Eastern Pacific Oscillation (EPO).

When this upper ridge pokes northward, it can dislodge cold air in Alaska and western Canada and send it careening into the central and eastern U.S.

In fact, a 2019 study published in Geophysical Research Letters found a pattern with an Alaskan ridge of high pressure was most important for widespread severe cold in North America.

So this is another pattern on the way that could eventually deliver more cold into the U.S. in the coming weeks.

The upper-level pattern beginning the week of Jan. 10 is expected to evolve to a stronger nose of high-pressure aloft near the West Coast, potentially nosing toward Alaska. This positive PNA pattern generally works to tap colder air from Alaska and Canada into the central and eastern U.S.

The upper-level pattern beginning the week of Jan. 10 is expected to evolve to a stronger nose of high-pressure aloft near the West Coast, potentially nosing toward Alaska. This positive PNA pattern generally works to tap colder air from Alaska and Canada into the central and eastern U.S.3. Weaker Polar Vortex

You've likely heard the term "polar vortex" virtually every winter since it first entered into popular culture during a bitter cold January 2014.

The polar vortex is a whirling cone of low pressure over the poles that's strongest in the winter months due to the increased temperature contrast between the polar regions and the mid-latitudes, such as the United States and Europe.

This isn't like a storm you might think of in the lower atmosphere, with cold and warm fronts producing rain or snow. Instead, the polar vortex occurs primarily in the stratosphere, a layer of the atmosphere about 6 to 30 miles above the ground – above most of the weather with which you're familiar occurs.

Strangely, when this polar vortex is strong, cold air is less likely to plunge deep into North America or Europe. Picture this strong vortex fencing off the coldest air from the U.S. and Europe. This was in place much of last winter.

In December, however, the atmosphere threw a curveball.

A sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event originating over Siberia sent temperatures rocketing 50 degrees Celsius warmer over the North Pole stratosphere in just a few days.

These temperature spikes are actually quite common, occurring on average once every other winter, according to data compiled by Amy Butler, an atmospheric scientist and expert on SSW events at NOAA.

This sudden warming weakened, stretched and displaced the polar vortex off the North Pole, as you can see in the animation below from Judah Cohen, director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER), a Verisk Business.

When that happens, the weaker polar vortex and stratospheric warmth can drip down to affect the jet-stream patterns in such a way to enhance the previous two blocking patterns mentioned above, opening the floodgates for colder air into the U.S. and Europe.

And those blocking patterns could have staying power.

"All we really know is that the AO/NAO are predominantly in the negative phase for up to two months following an MMW (major mid-winter warming, an extreme case of an SSW)," wrote Cohen in a Jan. 4 blog.

That means the Greenland block pattern could persist in some form into February or even March.

"It's typical one week or so after the SSW event peaks over the North Pole to see upper-level ridging build over Alaska," Ventrice told weather.com, referring to the pattern discussed earlier.

What Does This Mean for the Rest of Winter?

Cohen cited the two most recent SSW-polar vortex disruption events, each with far different outcomes.

The February 2018 event triggered a pair of "Beast From the East" March cold outbreaks in Europe – where impacts from polar vortex weakening typically first occur. That was then followed by a parade of four nor'easters that hammered the U.S. East Coast in March and prolonged April cold in the nation's midsection.

Visible satellite image composite of the four nor'easters of March 2018.

Visible satellite image composite of the four nor'easters of March 2018.But the most recent SSW case was a cautionary tale against taking a stormier outlook as a slam dunk.

After the January 2019 SSW event, much of the eastern U.S., Europe and Siberia remained mild, as the Greenland block was absent.

"I think the background state of the atmosphere preceding and during the SSW currently is more like 2018 than 2019," Cohen told weather.com referring to more blocking, a warmer Arctic and colder weather in Eurasia.

A study lead by Cohen coincidentally published during that same March 2018 plague of nor'easters found a warmer Arctic can lead to more severe winter weather in the eastern U.S.

But, Cohen likened this outlook to the NBA Draft: "Great potential doesn't always translate into commensurate reality."

Regardless of how the pattern evolves, we're also headed for what has historically been the peak time of year for East Coast snowstorms, from late January through February.

So fasten your seatbelts – the rest of winter may be a wild ride in the U.S. and Europe.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment