Tom Niziol

The recent snowstorm that clobbered the mountainous West produced several feet of snow in many remote locations.

Places way up in the mountains from the Sierra through Cascades, Wasatch and Rockies are extremely difficult to get to, even in the summer months.

In winter, when there may be as much as 20 to 25 feet of snow on the ground and full-blown blizzards may be raging, it is impossible to reach these spots to measure snow.

So how do they do it and why?

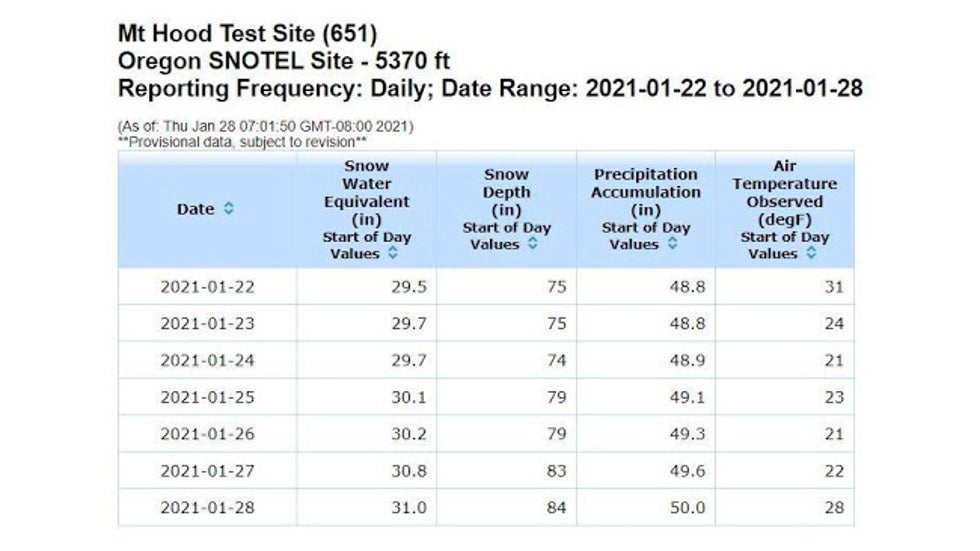

Weather data including the snow depth and snow water equivalent (SWE) from the Snow Telemetry site on Mt. Hood, Oregon.

Weather data including the snow depth and snow water equivalent (SWE) from the Snow Telemetry site on Mt. Hood, Oregon.In the West, it all has to do with the water supply, and much, if not most, of that water comes from the snow water equivalent (SWE), or the melted snow from the snowpack.

According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), “50 to 80 percent of the water supply in the western United States comes from the snowpack.”

SPONSORED: 40% off Valentine's Day sale at Michael's

Think about that – water for drinking, bathing and all your household chores. That same water supply is also extremely important for agriculture, recreation, flood management and power generation.

Utility companies need to know how much of their electricity generation will come from hydropower. Agricultural interests need this information to plan for crop planting patterns, groundwater pumping needs and irrigation schedules.

Those huge flood control projects must determine how much water they can safely store in reservoirs. Finally, municipalities rely on this data to evaluate their water supply, and as we have seen all too often in the past few decades, determine whether or not water rationing might be necessary.

Outdoor recreation relies on water information to determine ski conditions in winter and rafting conditions year-round. Fish releases are also dependent on water forecasts.

And in a world now dominated by a rapidly changing climate, this information is even more important. The data is a basis for climate studies, air and water quality investigations, climate change and even endangered species habitat analysis.

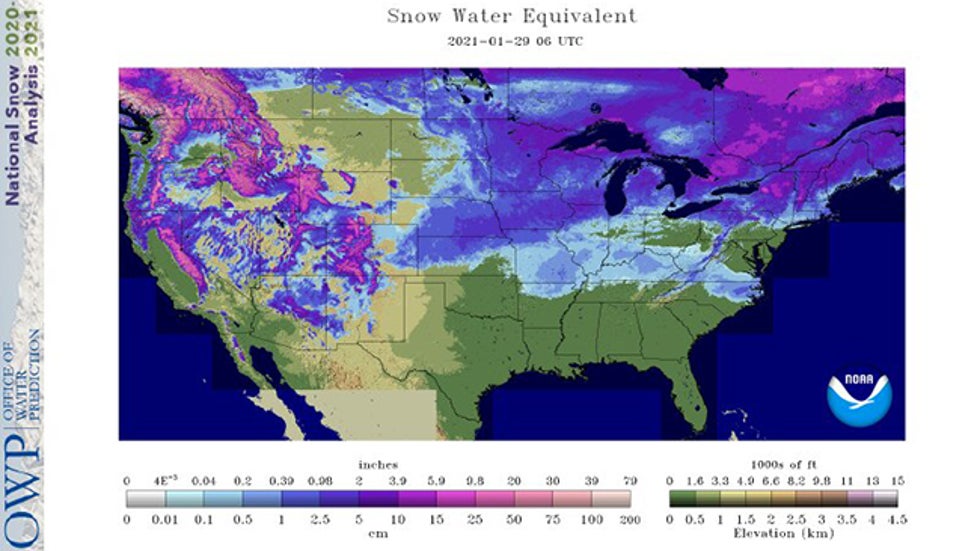

An analysis of snow water equivalent (SWE), or water content of the snowpack, across the U.S. on Jan. 29, 2021.

An analysis of snow water equivalent (SWE), or water content of the snowpack, across the U.S. on Jan. 29, 2021.But how do you accurately get measurements of snow depth and SWE from tens of thousands of square miles of remote mountainous locations across the western U.S.?

It comes to us from the Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) network, an automated data collection network that started in 1977, designed to gather information on the snowpack as well as other climate data across the western U.S. and Alaska.

At last count, there were over 800 stations in the network, all located in those remote, high-elevation mountain watersheds that are not only tough to get to, but can be dangerous due to the threat of avalanches.

The equipment is designed so it can gather and transmit its data automatically, powered by only solar cells and batteries, without someone coming up to maintain them for up to a year.

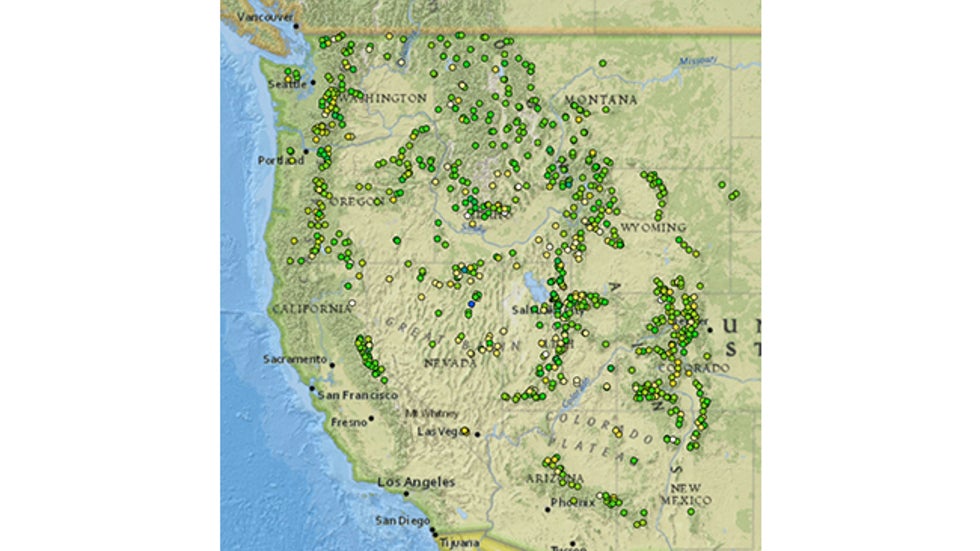

Locations of Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) sites across the western U.S. There are over 800 remotely-located stations in the western U.S. and Alaska.

Locations of Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) sites across the western U.S. There are over 800 remotely-located stations in the western U.S. and Alaska.The basic instruments that comprise a SNOTEL measure snow depth, water content, rainfall and air temperature, as well as wind and solar radiation.

Some SNOTEL sites are specially equipped to also measure soil moisture and soil temperature at various depths.

Some of these parameters are pretty easy to measure, like using a thermometer for temperature or a rain gauge for the rainfall. Measuring the snow depth and the water content of the snow, however, are not that easy.

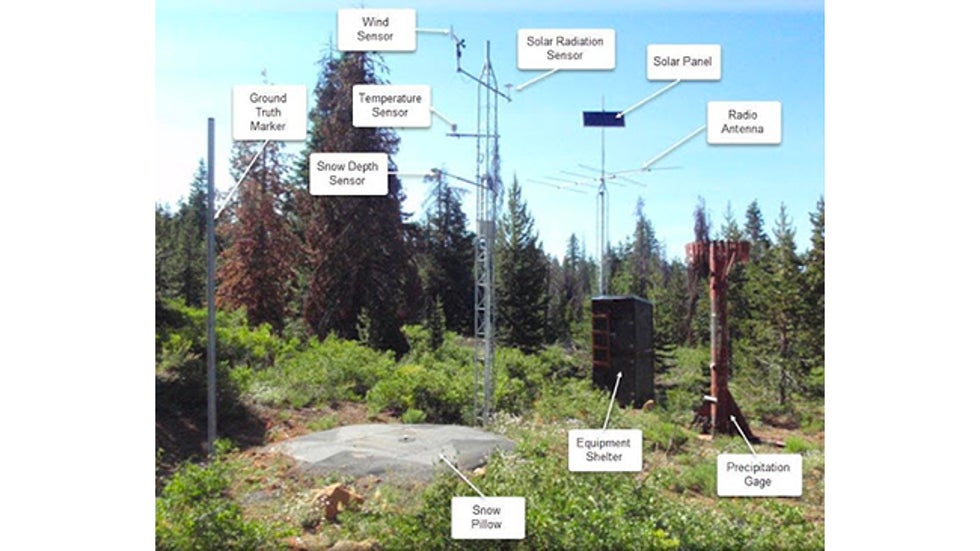

Here is a typical SNOTEL instrument package. Note the acoustic snow sensor, located directly above the snow pillow.

Here is a typical SNOTEL instrument package. Note the acoustic snow sensor, located directly above the snow pillow.Those are measured by a couple of clever little sensors.

Snow depth is measured by an ultrasonic sensor that works by measuring how long it takes for an ultrasonic pulse to travel from the sensor, located several feet above the ground, to the surface of the snow and back. It’s kind of like sonar on a submarine. It’s an ingenious device and works quite well.

Knowing the depth of the snow is only part of the answer that water managers are looking for.

A 4-foot depth of snow that is fresh and fluffy may only contain a third of the water that a wet, heavy, slushy snowfall might contain.

The real payoff comes from determining just how much water is in the snowpack.

That is done by another ingenious device, the snow pillow. Designed to sit on a piece of flat ground, most snow pillows are constructed with sheets of stainless steel that form an airtight container filled with an antifreeze solution.

As snow piles up on the steel plates, it weighs it down, displacing the antifreeze, and a sensor measures that hydrostatic pressure. Simply put, the snow pillow measures the weight of the water in the snowpack.

The SNOTEL data is transmitted by a principle of radio transmission called meteor burst.

Radio signals are aimed skyward where the trails of meteorites reflect or reradiate the signals back to Earth. This allows the sites to communicate their data over a thousand miles, if necessary, to receiving networks in Boise, Idaho, and Ogden, Utah.

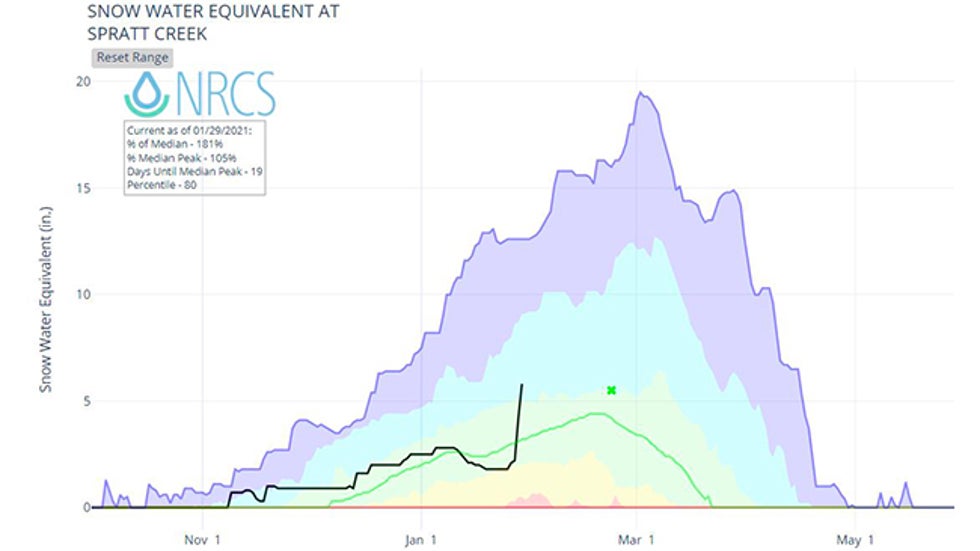

Season-to-date snow water equivalent (black line) in inches at Spratt Creek, California, in the Sierra near Lake Tahoe through Jan. 29, 2021, compared to the 10th (orange), 30th (yellow), 50th (light green), 70th (teal) and 90th (blue) percentiles through a given water year. The thin green line is the median SWE. Note the sharp climb from the late January atmospheric river event.

Season-to-date snow water equivalent (black line) in inches at Spratt Creek, California, in the Sierra near Lake Tahoe through Jan. 29, 2021, compared to the 10th (orange), 30th (yellow), 50th (light green), 70th (teal) and 90th (blue) percentiles through a given water year. The thin green line is the median SWE. Note the sharp climb from the late January atmospheric river event.Of course, the SNOTEL Network is not the only means used to record snowfall and SWE across the West.

There is an entire armada of sensors, programs and even human measurements taken on a regular basis to monitor snow depth and SWE across the West.

These include snow surveys like the ones conducted by the California Department of Water Resources throughout the winter.

In addition, there have been many advances in measuring snow information by remote sensors, including aircraft and even satellite equipped sensors.

However, the 800-plus SNOTEL network is the workhorse of monitoring the snowpack across the West.

Helicopters fly scientists into remote areas, as well, to measure the snowpack as we see here in Utah.

Helicopters fly scientists into remote areas, as well, to measure the snowpack as we see here in Utah.With these measurements, we not only get to learn how much snow is in remote areas from the most recent winter storm. We can also constantly monitor the amount of water in that snowpack across large areas.

Those measurements will help water managers plan for the dry season that begins in the spring and lasts through much of the summer in the West.

Knowing the state of the snowpack can also help avalanche forecasters assess the potential dangers from that snowfall record.

It's all due to an excellent network of remote equipment that keeps working every day to provide daily information on the state of the winter in some of the most remote locations across our nation.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment