A brief tornado along the Oregon coast Tuesday was the state's first January tornado this century and Tuesday's only report of severe weather anywhere in the United States.

The tornado touched down just north of Manzanita, Oregon, about 60 miles west-northwest of Portland, at 11:15 a.m. PST Tuesday.

According to a National Weather Service damage survey, two properties sustained minor damage, including a broken window on one home, and damage to parts of a fence and a metal roof on another property dislodged on one side.

A tree was blown down and another was snapped. The NWS rated the damage EF0, with peak winds estimated at 65 to 70 mph.

Tuesday's tornado was the first January tornado in Oregon since a Jan. 5, 1998, tornado, also along the coast in Seaside, according to the NWS.

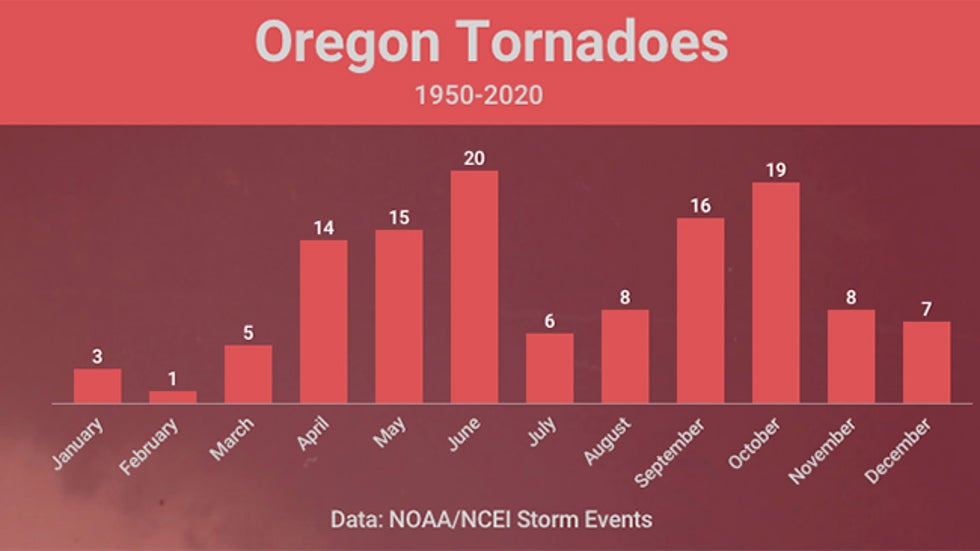

Since 1950, only 11 Oregon tornadoes, including Tuesday's tornado, have occurred in the winter months of December, January or February, according to NOAA's Storm Events database.

In western Washington, four separate tornado warnings were issued over about a half-hour period late Tuesday afternoon in Grays Harbor County, about 40 miles west of the state's capital, Olympia.

No tornadoes or damage were reported from the thunderstorms, which passed over the cities of Hoquiam and Aberdeen.

The Oregon tornado was the only report of severe weather anywhere in the nation Tuesday, which is unusual for this time of year.

It Wasn't Too Cold for Tornadoes

Most tornadoes occur on warm, humid days ahead – to the east – of a cold front.

So how did thunderstorms capable of spawning tornadoes form on a January day in the Pacific Northwest?

The key to thunderstorm formation is convective instability, namely, the tendency for air to rise, similar to the convection you see when boiling water on a stove.

Instability is highest when hot, humid air near the ground is topped by cold, dry air several thousand feet above the ground.

Sometimes, particularly along the West Coast, the cold air several thousand feet above the ground is so cold that the column of air is unstable regardless of whether air near the ground is all that warm.

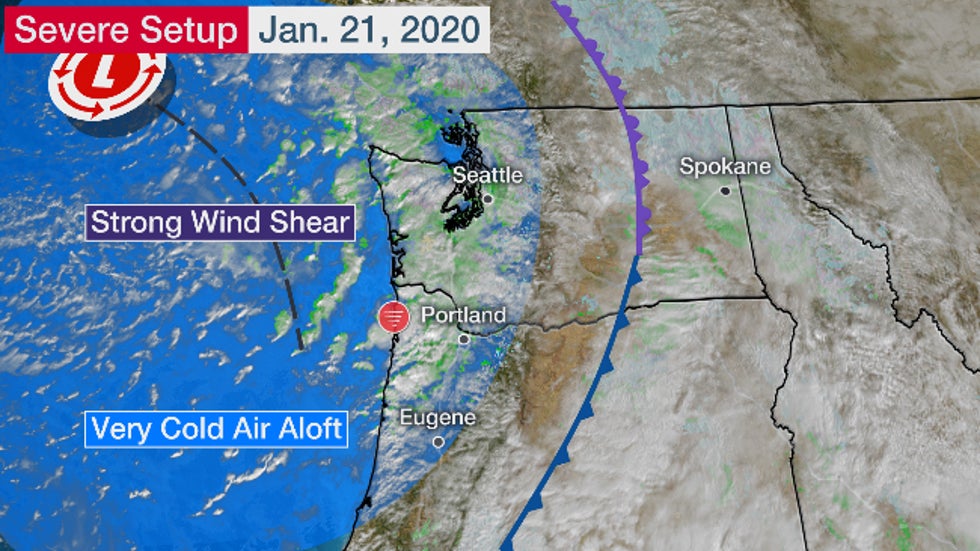

That was the case Tuesday.

Temperatures in northwestern Oregon were only in the upper 40s, but air about 17,000 feet above the ground – roughly at the 500-millibar level meteorologists typically examine – was about minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit over western Washington.

It wasn't enough instability to trigger deep, explosive thunderstorms as you would see in the Plains in spring. Instead, smaller, shorter, low-top thunderstorms formed off the Oregon and Washington coasts and moved ashore.

The other ingredient, wind shear, was plentiful.

This change in wind speed and/or direction with height is what helps generate rotating thunderstorms.

Tuesday's same strong upper-level system that generated such cold air aloft also produced an environment of deep spin, known to meteorologists as vorticity.

Any thunderstorm able to blossom in such an environment was capable of generating at least a short-lived tornado or waterspout.

Manzanita, Oregon, was also hit by an EF2 tornado in October 2016, one that moved ashore as a waterspout. It was only the fifth tornado as strong or stronger in the state since 1950.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.

No comments:

Post a Comment